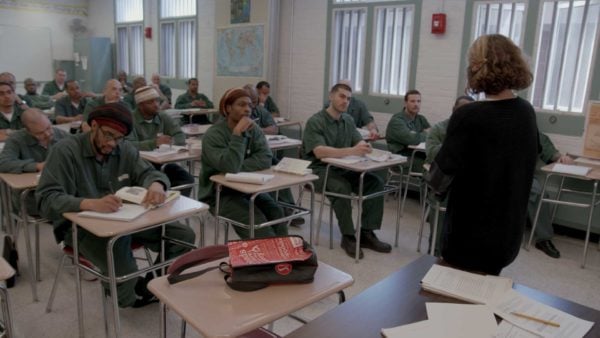

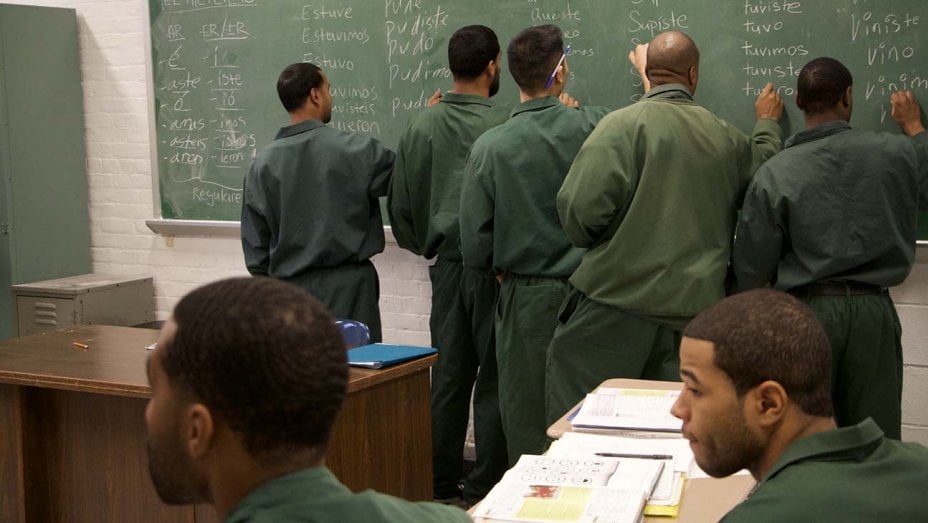

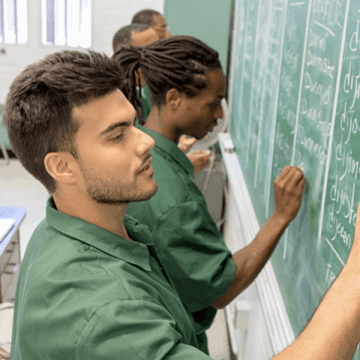

Bard Prison Initiative students conjugate Spanish verbs at Eastern Correctional Facility. (Skiff Mountain Films)

Rodney Spivey-Jones looked up at his face on the TV screen bolted high on the wall, but his attention was on the men around him. Garbed in green sweatshirts and canvas pants, they sat in seven rows of folding chairs in an otherwise vacant gymnasium, still and silent, watching an advance screening of the new PBS docuseries College Behind Bars.

The men are prisoners at Fishkill Correctional Facility in upstate New York; they are also college students. That they can be both at the same time is credit to the Bard Prison Initiative, a full-time, degree-granting program that is the subject of the film. Spivey-Jones had already seen earlier rough cuts, so although it was always intense watching himself on camera, at this screening he focused on how the other men were reacting. “They were listening,” he later explained, “because so much of what I had to say resonated with them.”

College Behind Bars, which airs on PBS Monday and Tuesday night, offers TV audiences a rare window into the U.S. correctional system. But for the men gathered on this October afternoon, it was more of a mirror. Spivey-Jones knew that BPI — and the men themselves — had a lot riding on what it reflects. “Whenever you have an opportunity to talk about who you are and where you came from, you should take that chance,” he said. “Otherwise, someone else is creating our narrative for us. And when they create our narrative for us, they’re defining us. And once they define us, it’s pretty hard to define yourself after that.”

A college education had been a goal for Spivey-Jones since he was a teen, but one tragically intertwined with his path to prison. In 2002, at the age of 19, he was living in Syracuse and had enrolled at SUNY Onondaga, but he couldn’t afford the tuition. When his job cut back his hours, he turned to crime to make ends meet, and on a February afternoon, he’d pulled a gun on a man on the back of a Syracuse bus and tried to rob him. In the ensuing argument Spivey-Jones fired a single shot, and by the end of that night he was arrested for murder. He’s been behind bars ever since.

It was devastating for his younger sister, Elitha Smith. She and Spivey-Jones had shared a tough childhood, which they recount in College Behind Bars: Their mother, who struggled with schizoaffective disorder, died by suicide at 32, and two years later their grandmother, who had taken custody of the children, also passed away. “When my brother went into prison, basically, I lost everything,” Smith told me.

She managed to navigate those perilous circumstances, earning acceptance to West Point and later completing two tours in Afghanistan, first conducting convoys and then as a human resource officer. Today she’s a nurse in a cardiothoracic unit at Duke University. But it’s still strange to her that she and her brother wound up on the same river in such different institutions. “I feel like I could throw a rock from West Point to Fishkill,” she said.

Rodney Spivey-Jones ’17, right, and his senior project adviser Daniel Berthold, professor of philosophy. (Skiff Mountain Films)

At the screening, Spivey-Jones leaned forward, elbows on his knees, occasionally recording his thoughts in a dog-eared notebook. On a basic level, College Behind Bars documents what happens when he and other imprisoned men, who have little to do beyond count down the years of their sentences, are given the opportunity to get an education. Prospective BPI students must complete an essay and interview to vie for admission to the highly competitive program, which gets about seven applicants for every spot. Those admitted can pursue degrees in more than a dozen courses of study, working their way to an associate’s degree and then a bachelor’s. Many of the instructors are faculty at Bard College, and they hold BPI students to the same high standards as their other undergraduates.

And as College Behind Bars shows, the BPI students thrive. Spivey-Jones excelled scholastically, majoring in social studies. When he graduated in 2017 he was awarded the highest possible marks on his thesis, “Messianic Black Bodies,” which drew connections between the deaths of Emmett Till and Michael Brown. In the film, his adviser, Daniel Berthold, a Bard College philosophy professor, describes him as “without a doubt one of the most terrific students I’ve ever had, anywhere.” A sequence in which Spivey-Jones and BPI’s debate team best Harvard’s — a victory that prompted international headlines — provoked the biggest laughs. “That’s the happiest section so far,” remarked a man in the back row.

But a liberal-arts education can play a crucial role in the experience of accountability as well. In conversation after the screening, Spivey-Jones pointed out that programs offered to prisoners typically target specific problems such as substance abuse or anger management. “We rarely get a chance to think about how we hurt the victims,” he said. “And yet that’s something that’s required of us when we go to the parole board.” He contrasted that with a literature class, where you might read about feelings experienced by the characters and then recognize in them your own. “Once you can empathize with other people, you can realize that you’ve caused a lot of harm,” he said. “If you can connect your pain to the pain that you’ve caused, there’s a responsibility there. And it’s hard to escape it.”

The access these men have had to higher education is exceptional; the vast majority of people in U.S. prisons do not. But it hasn’t always been that way. The film chronicles how, as recently as the early 1990s, hundreds of prison college programs enrolled tens of thousands of incarcerated students, who relied primarily on federal Pell Grants to cover their tuition. Research showed that the programs were so successful at cutting recidivism and easing reentry that they essentially paid for themselves. But the 1994 federal crime bill changed all of that by barring incarcerated people from those grants. Within years, higher education in the nation’s correctional system essentially disappeared.

“That happened at precisely the time when more people were in prisons than ever before, when the prisons became a central organizing institution in American life,” BPI’s executive director Max Kenner told me. He founded BPI in 1999 while he was himself still an undergraduate at Bard College, and his foremost hope for College Behind Bars is that it persuades Americans to reinstate prisoners’ access to Pell Grants. (Bipartisan legislation to do so has already been introduced in the U.S. Senate.) Kenner has managed to sustain BPI with philanthropic dollars as it has grown to offer more than 160 courses annually, but it still only operates in six of New York’s 52 prisons, enrolling 300 students of some 50,000 people incarcerated across the state.

More fundamentally, the film addresses a challenge at the heart of debates over the criminal-justice system. To date, reform efforts to shorten excessively punitive sentences have not generally extended beyond nonviolent or drug offenses, yet people convicted of violent crimes fill the majority of U.S. prison beds. Advocates increasingly recognize that we cannot end mass incarceration without transforming our societal response to violence. College Behind Bars presents an unusually complex portrait of men and women convicted of such crimes.

In discussion following the screening, the audience expressed its appreciation for the way the film handled this issue. A man with a deep voice observed that the characters were not introduced through their convictions, a contrast with how media typically define prisoners through the lens of the worst thing they’ve ever done. But over the course of College Behind Bars, Spivey-Jones and other characters do ultimately disclose the events that put them in prison. This allows viewers, who have first gotten to know the men and women as inspired college students, to stretch their empathy past crimes they might not typically feel able to look beyond. A bearded man with dreadlocks stood to personally thank Spivey-Jones for baring his own story in that way. “I have a violent crime myself,” he said.

Director Lynn Novick, a longtime collaborator of Ken Burns, acknowledged that when the project began in 2013, she envisioned focusing on the characters’ present-day studies, not their pasts. “Our early proposals don’t bear much resemblance to what the film ended up being — these deeply intimate personal stories of reckoning and rehabilitation and awakening,” she said. Novick recalled how, on one of the first days of shooting, the crew overheard a group of students outside the prison library discussing a class in which they were reading Othello, Macbeth, and Oedipus Rex, and one of them asked aloud: “Is my life a tragedy?” That stuck with her. Producer Sarah Botstein credited the subjects with ultimately pushing them in this direction, to address where they came from and why they ended up in prison. “They were part of that journey with us,” she said.

In sharing his own story, Spivey-Jones said he doesn’t mean to diminish the crime he committed, but he hopes the series gives viewers a glimpse of his humanity, too. “I don’t want the victim or his family to get lost either. Their identity shouldn’t be lost. These are real people, in the same way that incarcerated people are real people. And that’s a very tough balance to strike.” Watching Spivey-Jones struggle with guilt for a crime he takes responsibility for but can’t undo, viewers are reminded that accountability is essential for justice, but so, too, is absolution.

“I don’t think you ever know when someone has paid a sufficient price for their crime,” his sister says. But Smith sees his path to redemption as a process of storytelling, too. “One of the biggest hurdles my brother’s going to have to go through is letting all those people in the past who knew him and knew the crime know: That kid back then wasn’t who I was. I’m here now. I’m here to do something good — not only for myself, my family, my society — but also for you.”

As the screening concluded, the men folded the chairs and cleared the gymnasium. Stepping outside, the filmmakers headed along the razor wire toward the exit, where a sign read: “Please make sure the gate is closed tight.” Back down the hill, men could be seen walking in the other direction toward the dormitory for one of the day’s mandatory head counts, Spivey-Jones among them. He has served 17 years of his sentence; he will not be eligible for parole until 2022.