Since 2014, almost 100 students have been members of the BPI Debate Union, building a successful record against debaters from internationally respected programs including teams such as Harvard, Cambridge, and Morehouse. Read More

BPI Blog

Category: Debate Union

Five Years Since Harvard Win

This month marks the five year anniversary of the BPI Debate Union's win against Harvard in September 2015. While the team had been racking up wins since well before the Harvard match, the meet up with Harvard brought international attention to their efforts and… Read More

Three Prison Inmates Beat Harvard in a Debate. Here’s What Happened Next.

Dyjuan Tatro speaks with audience members after the screening of ‘College Behind Bars’ at the New York Film Festival this month. JAMES SPRANKLE FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

When inmates in a New York maximum-security prison beat Harvard in a debate four years ago, their victory made international headlines and highlighted the intellectual talent behind bars.

Now, the three debaters who outsmarted the Ivy Leaguers have a new round of accomplishments. Two have found professional footing after release. The third, still in prison, has earned a master’s degree and wants to work in public health someday.

They say they always will feel bonded to their debate team at the Bard Prison Initiative, which offers free college to incarcerated men and women. They aim to prove the power of a rigorous education to turn lives around.

“We hope we can tell a story that changes the narrative of who people in prison are,” said Dyjuan Tatro, who took the debate stage that high-pressure afternoon inside Eastern New York Correctional Facility in the Catskills. He calls his team’s triumph “a story about hard work, redemption and hope.”

The debate team at the Bard Prison Initiative, which offers free college in New York prisons, made international news when it beat Harvard four years ago. Here is a first glimpse of the competition, from a new PBS documentary, “College Behind Bars.” Photo: PBS

The Bard Prison Initiative, part of Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, enrolls more than 300 students inside six New York prisons.About 20 men at a time earn coveted spots on the debate team at Eastern, which has lost only two of its 11 matches in six years. This past spring, it beat challengers from the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom.

The win over Harvard provides one of the emotional peaks in a new four-hour documentary, “College Behind Bars,” which explores the lives of people serving time for serious offenses and struggling to become productive citizens.

Directed by Lynn Novick and executive produced by Ken Burns, the series will air Nov. 25 and 26 on PBS.

‘Defying Expectations of Who College Is For’

With a broad smile and close-cropped beard, Mr. Tatro cuts an elegant figure as he juggles meetings and calls at work. Thirty-three years old, he was released from prison two years ago, after 12 years of incarceration for assault, and now has a bachelor’s degree from Bard College as a math major.

He worked for U.S. Rep. Sean Patrick Maloney during his unsuccessful bid for New York attorney general, advising the Democrat on criminal-justice issues. They met when the congressman took an interest in Bard’s model for college in prison, which has been replicated nationwide.

Dyjuan Tatro was a member of the Bard Prison Initiative debate team at Eastern New York Correctional Facility that beat Harvard University in 2015. PHOTO: JAMES SPRANKLE FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

Now Mr. Tatro, who lives in Manhattan, is a government-affairs and advancement officer for the Bard Prison Initiative, trying to help lawmakers understand its goals and fund its expansion.

“We’re in the business of defying expectations of who college is for and where it might lead,” he said.

The prison initiative depends mostly on private donors. Its leaders are pushing for the broad restoration of federal Pell grants for tuition for incarcerated students. Prisoners were ineligible for Pell grants after the 1994 crime bill became law.

Then in 2016, the U.S. Department of Education allowed a small group of colleges, including Bard, to tap such funds through a “Second Chance Pell” pilot, which recently was renewed with bipartisan support.

Critics say tax dollars shouldn’t pay for college for felons when many law-abiding citizens are racking up massive student debt. “Resources should be dedicated to struggling middle-class families who are finding it hard to afford college for their own kids,” said Scott Reif, spokesman for Republican leadership in the New York state Senate.

Supporters of prison education quote a nonpartisan Rand Corp. study that found such programs save money by reducing recidivism.

The average annual cost for each person in a New York prison is $69,000, by state data, and about 40% of offenders return to custody within three years of release. The Bard Prison Initiative says its college program costs about $9,000 for each student yearly, and its alumni’s recidivism rate is less than 4%.

A ‘Passion’ for Giving Back to Others

At 35, Carlos Polanco is working on a memoir, relishing his mother’s chicken with sweet plantains and enjoying romantic novels by Nicholas Sparks. He talks of the simple pleasure of feeling free to buy books he spots on sale.

“I completely lose track of time reading and that’s been great,” he said.

When Mr. Polanco left prison two years ago, after serving 14 years for manslaughter, he ended up in a homeless shelter. He worked as a math tutor at several nonprofits, including one that helps college freshmen adjust to tougher workloads.

Carlos Polanco finished his bachelor’s degree at Bard College last year. He majored in applied mathematics in biology. PHOTO: JAMES SPRANKLE FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

“It’s a passion of mine to be able to give what I know to others, specifically students, so they can navigate those sort of rough waters that college tends to sometimes drown you in,” he said.

Mr. Polanco moved to a New York City apartment and finished his bachelor’s degree at Bard last year. He majored in applied mathematics in biology.

After stints as an office manager and personal trainer, Mr. Polanco now works as an accounts-payable analyst at 40 North, an investment business on the 46th floor of a Midtown Manhattan office tower with panoramic views. He tapped the Bard network to find that post.

“To debate, it’s necessary to fully immerse yourself in the subject matter, and that skill set translates into any job,” Mr. Polanco said.

Three [Incarcerated Students] Beat Harvard in a Debate. Here’s What Happened Next.

In 2015 the story of the Bard Prison Initiative Debate Union's win over Harvard became a global news story. Leslie Brody of the Wall Street Journal, who was there for the debate, first broke the story. Now, four years later, Brody reunited with the… Read More

How maximum security inmates took on Cambridge in a debate about nuclear weapons — and won

The three students from the University of Cambridge, wearing black suits and clutching sheaves of papers, stepped onto the wooden auditorium stage under the warm yellow lights. As members of a storied debate team, they had competed the world over but never in a… Read More

Prison vs. Harvard in an Unlikely Debate

In 2015 the story of the Bard Prison Initiative Debate Union's win over Harvard became a global news story. Leslie Brody of the Wall Street Journal, who was there for the debate, first broke the story. This article, reproduced below, first appeared in the… Read More

Prison vs. Harvard in an Unlikely Debate

NAPANOCH, N.Y.—On one side of the stage at a maximum-security prison here sat three men incarcerated for violent crimes.

On the other were three undergraduates from Harvard College.

After an hour of fast-moving debate Friday, the judges rendered their verdict.

The inmates won.

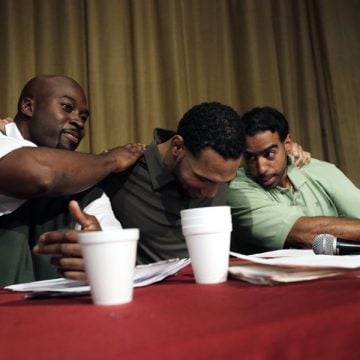

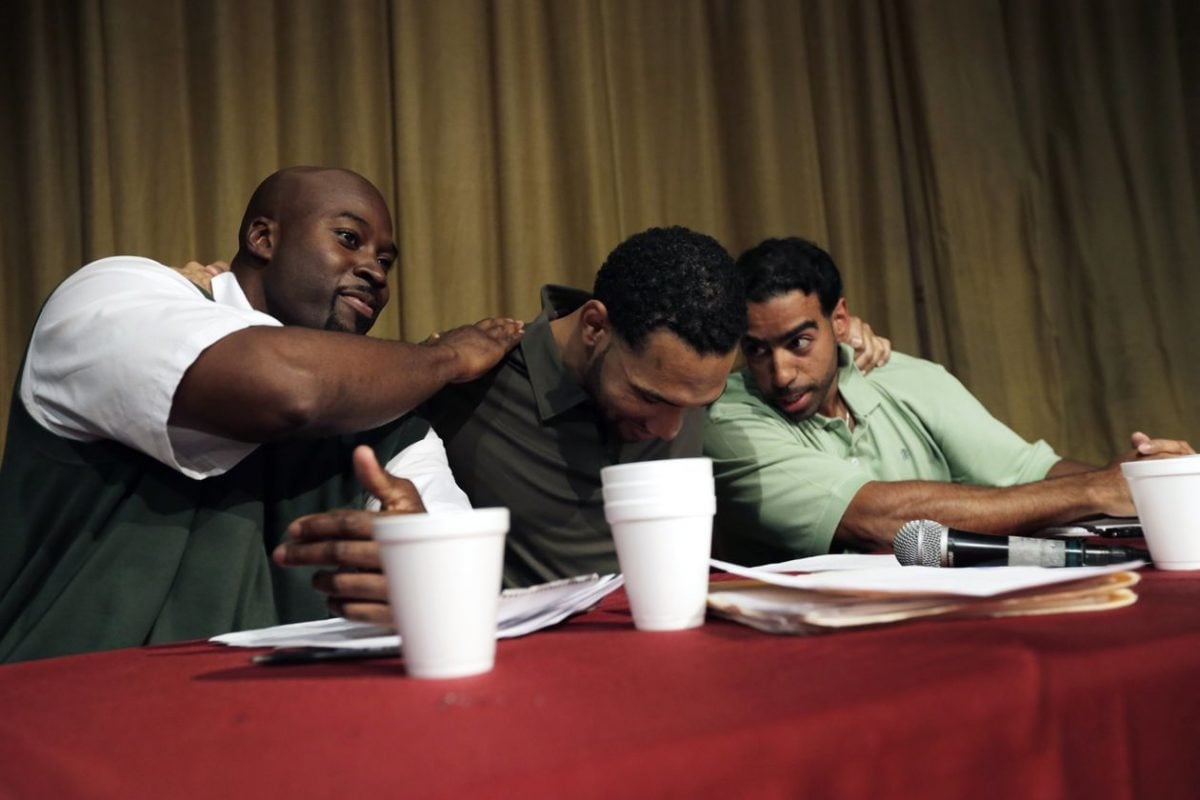

Prison inmates and members of the Bard Prison Initiative Debate team debate against Harvard College Debating Union at the maximum security Eastern New York Correctional facility in Napanoch, New York on Friday, September 18th, 2015. Peter Foley for The Wall Street Journal

The audience burst into applause. That included about 75 of the prisoners’ fellow students at the Bard Prison Initiative, which offers a rigorous college experience to men at Eastern New York Correctional Facility, in the Catskills.

The debaters on both sides aimed to highlight the academic power of a program, part of Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y., that seeks to give a second chance to inmates hoping to build a better life.

Ironically, the inmates had to promote an argument with which they fiercely disagreed. Resolved: “Public schools in the United States should have the ability to deny enrollment to undocumented students.”

Carlos Polanco, a 31-year-old from Queens in prison for manslaughter, said after the debate that he would never want to bar a child from school and he felt forever grateful he could pursue a Bard diploma. “We have been graced with opportunity,” he said. “They make us believe in ourselves.”

Judge Mary Nugent, leading a veteran panel, said the Bard team made a strong case that the schools attended by many undocumented children were failing so badly that students were simply being warehoused. The team proposed that if “dropout factories” with overcrowded classrooms and insufficient funding could deny these children admission, then nonprofits and wealthier schools would step in and teach them better.

Ms. Nugent said the Harvard College Debating Union didn’t respond to parts of that argument, though both sides did an excellent job.

The Harvard team members said they were impressed by the prisoners’ preparation and unexpected line of argument. “They caught us off guard,” said Anais Carell, a 20-year-old junior from Chicago.

Prison inmates and members of the Bard Prison Initiative debate team, from left: Carl Snyder, Dyjuan Tatro and Carlos Polanco embraced after winning a debate against Harvard at the Eastern New York Correctional facility in 2015. PHOTO: PETER FOLEY FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

The prison team had its first debate in spring 2014, beating the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y. Then, it won against a nationally ranked team from the University of Vermont and in April lost a rematch against West Point.

Preparing has its challenges. Inmates can’t use the Internet for research. The prison administration must approve requests for books and articles, which can take weeks.

In the morning before the debate, team members talked of nerves and their hope that competing against Harvard—even if they lost—would inspire other inmates to pursue educations.

“If we win, it’s going to make a lot of people question what goes on in here,” said Alex Hall, a 31-year-old from Manhattan convicted of manslaughter. “We might not be as naturally rhetorically gifted, but we work really hard.”

Ms. Nugent said it might seem tempting to favor the prisoners’ team, but the three judges have to justify their votes to each other based on specific rules and standards.

“We’re all human,” she said. “I don’t think we can ever judge devoid of context or where we are, but the idea they would win out of sympathy is playing into pretty misguided ideas about inmates. Their academic ability is impressive.”

The Bard Prison Initiative, begun in 2001, aims to give liberal-arts educations to talented, motivated inmates. Program officials say about 10 inmates apply for every spot, through written essays and interviews.

There is no tuition. The initiative’s roughly $2.5 million annual budget comes from private donors and includes money it spends helping other programs follow its model in nine other states.

Last year Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a Democrat, proposed state grants for college classes for inmates, saying that helping them become productive taxpayers would save money long-term. He dropped the plan after attacks from Republican politicians who argued that many law-abiding families struggled to afford college and shouldn’t have to pay for convicted criminals to get degrees.

The Bard program’s leaders say that of more than 300 alumni who earned degrees while in custody, less than 2% returned to prison within three years, the standard time frame for measuring recidivism.

In New York state as a whole, by contrast, about 40% of ex-offenders end up back in prison, mostly because of parole violations, according to the New York Department of Corrections and Community Supervision.