When it comes to incarceration, the United States of America is far and away the global leader in all the major categories. Based on data compiled by watchdog organizations, such as World Prison Brief and the Prison Policy Initiative, the American criminal justice system holds almost 2.3 million people in 1,719 state prisons, 109 federal prisons, 1,772 juvenile correctional facilities, 3,163 local jails, 80 Indian Country jails, and a smattering of military prisons, immigration detention facilities, civil commitment centers, state psychiatric hospitals, and prisons in outlying U.S. territories.

In 2015, the country with slightly more than four percent of the world population held 21 percent of the world’s inmates. Every year, some 630,000 men and women are released from U.S. prisons. In the near total absence of rehabilitation programs, within three years, nearly half of those released are back behind bars.

“Mass incarceration has crushing consequences: racial, social, and economic,” declares Michael Waldman, president of the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law, in the foreword to Ending Mass Incarceration: Ideas from Today’s Leaders, a 2019 survey containing essays by presidential candidates, community activists, authors, journalists, and policymakers. “We spend around $270 billion per year on our criminal justice system. In California it costs more than $75,000 per year to house each prisoner — more than it would cost to send them to Harvard.”

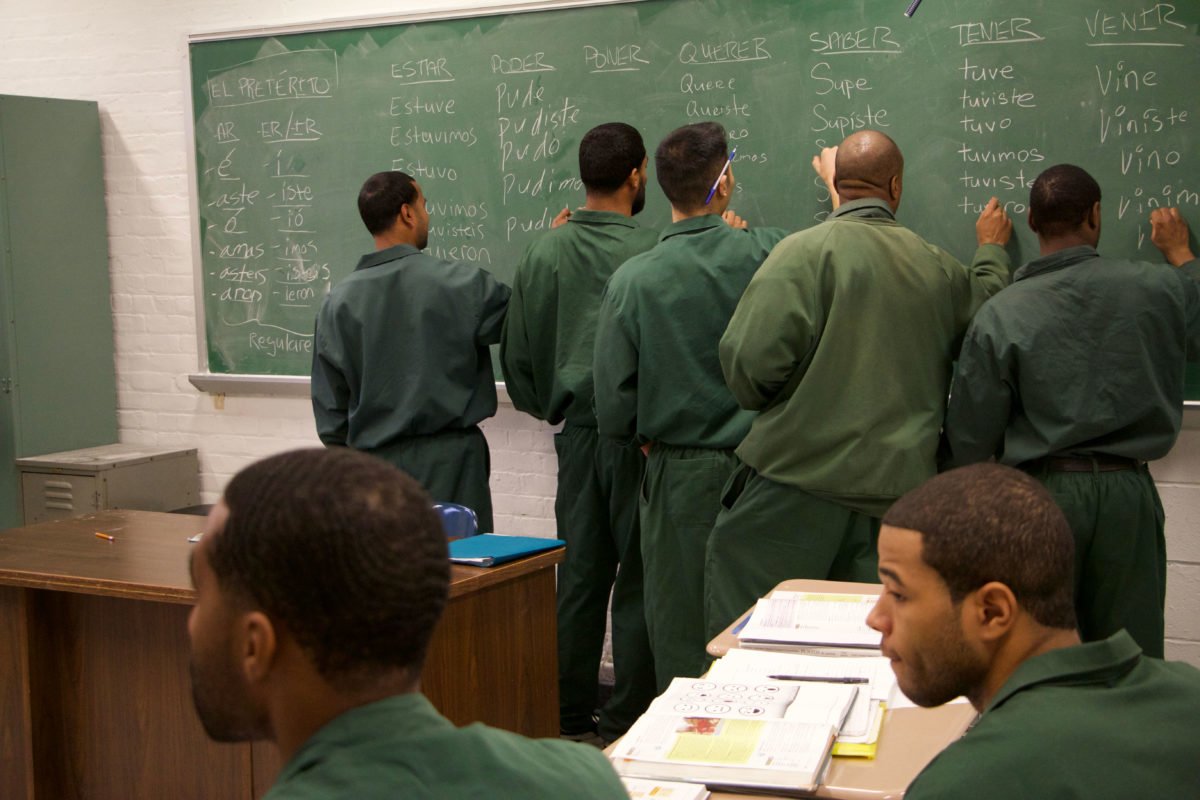

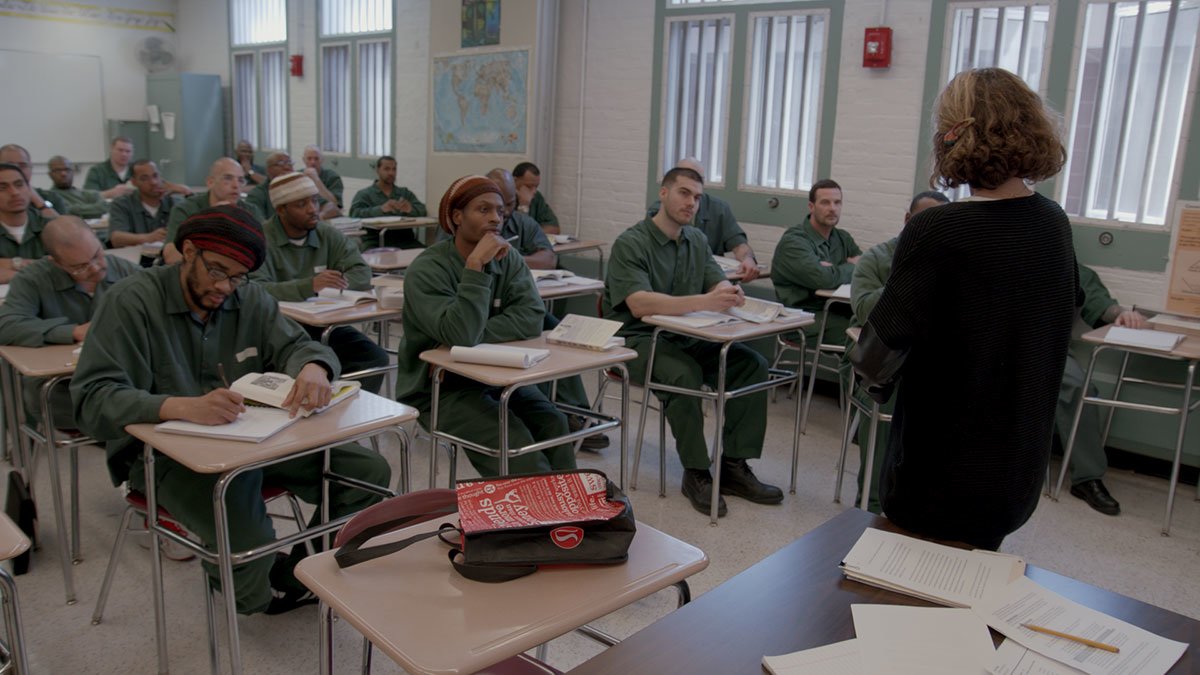

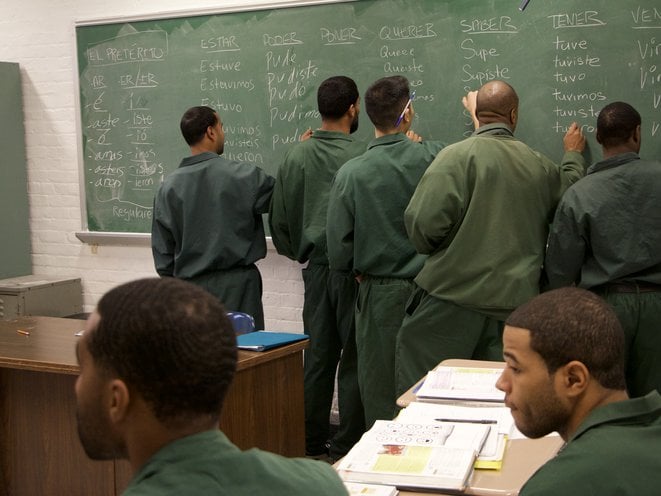

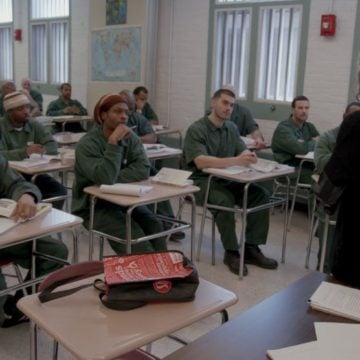

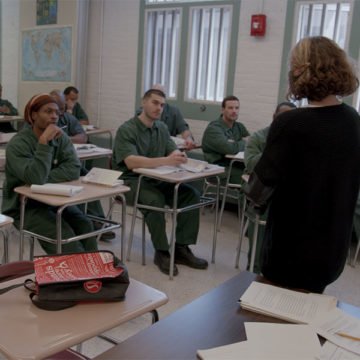

The cost comparison between incarceration and education is a telling point, one of many discussed in the national broadcast premier of College Behind Bars next Monday and Tuesday, November 25-26, at 9 p.m. on PBS (check local listings). The four-hour-long documentary (two hours per night) follows a small group of men and women grappling with the rigors of obtaining a higher education through the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI). Among the students are people who are serving time for serious crimes, including murder.

Shot over four years in maximum and medium security prisons in New York state, College Behind Bars was directed by Emmy and Peabody Award-winning filmmaker Lynn Novick (The Vietnam War, Frank Lloyd Wright), produced by Sarah Botstein, and executive produced by Ken Burns. Intense and compelling, the film offers an insightful glimpse into an existential crisis that should be a platform plank for every candidate during the unfolding election cycle.

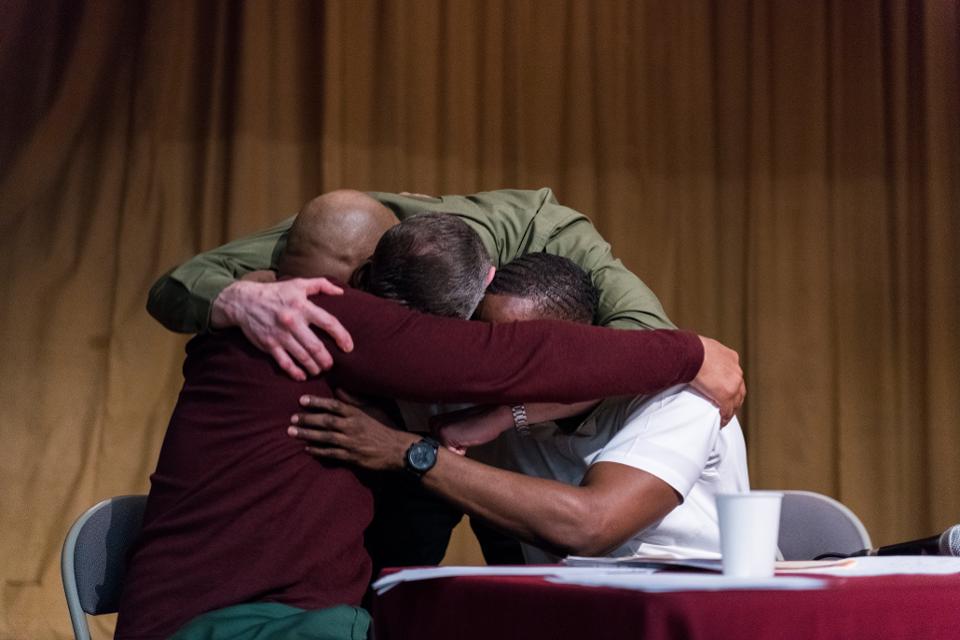

“Through the personal stories of the students and their families, the film reveals the transformative power of higher education and puts a human face on America’s criminal justice crisis,” notes a PBS press release. “It raises questions we urgently need to address: What is prison for? Who has access to educational opportunity? Who among us is capable of academic excellence? How can we have justice without redemption?”

Named for the college where it was founded by undergraduate students in 1999, the Bard Prison Initiative provides incarcerated men and women with an opportunity to earn a fully accredited diploma from the 160-year-old liberal arts institution in Annandale, New York. Currently, some 300 students in six prisons are enrolled in BPI at a cost of about $6,000 per student per year. Most of the funding is gleaned from private sources. Since BPI was launched, more than 500 alumni have been released; fewer than four percent have been sent back to prison.

Closer to home, the Georgia Department of Corrections administers one of the largest prison systems in the U.S. with nearly 52,000 incarcerated people under its supervision. Common Good Atlanta (CGA), a nonprofit co-founded in 2008 by Sarah Higinbotham and Bill Taft, teaches courses through Georgia State University to students at Phillips State Prison in Duluth, through Bard College (Clemente Course in the Humanities) at Whitworth Women’s Facility in Hartwell, and at the Metro Reentry Facility in south Atlanta. CGA recently launched a course in downtown Atlanta for previously incarcerated people.

“While we have no formal relationship, CGA is inspired and influenced by BPI’s emphasis on the humanities,” Taft explains.

CGA students enroll in a non-degree bearing program, which offers enrichment courses in subjects including literature, mathematics, history, and philosophy. The courses focus on critical thinking, written and oral communications, time management, teamwork, and self-advocacy. Since the program’s inception, more than 250 incarcerated men and women have taken CGA courses.

CGA’s campaign to bring the rehabilitative power of education to Georgia’s criminal justice system has not gone unrecognized. On October 24, in a ceremony in the Georgia State Capitol, Governor Brian Kemp presented Higinbotham and Taft with the 2019 Governor’s Award for the Arts and Humanities. The award recognizes individuals and organizations for their “significant contributions to Georgia’s civic and cultural vitality through excellence and service to the arts and humanities.”

On Monday, December 16, A Cappella Books will mark 30 years of continuous operation with a special concert benefiting Common Good Atlanta headlined by Chan Marshall. Better known as Cat Power, the singer-songwriter adopted the feline moniker at the beginning of her career when she was living in Cabbagetown. Atlanta-based W8ing4UFOs (led by Taft) and the unflappable guitar duo FLAP will open the concert at Variety Playhouse in Little Five Points (for more info, see Listening Post).

Up until the early 1980s, America’s prison population was somewhat commensurate with the country’s general population numbers. That alignment started skewing apart when “waging the war on drugs” and “getting tough on crime” became expedient mantras across the political spectrum. In 1994, Congress passed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act. Authored by then-Senator Joe Biden and signed into law by President Bill Clinton, the bill contained certain provisions, such as harsh sentencing for non-violent drug infractions and mandatory life sentences for repeat offenders, which sparked a quantum leap in America’s prison population.

One of the bill’s most contentious provisions was a ban on extending Pell Grants — which provide financial assistance to low-income families for college undergraduate and post-baccalaureate programs — to incarcerated people. This in spite of multiple studies proving the effectiveness of education as an instrument of rehabilitation.

In recent years, the socio-political pendulum has swung back in the other direction. In 2015, the Obama administration launched the Second Chance Pell pilot program, which reintroduced limited eligibility for Pell Grants to incarcerated people. Earlier this year, President Donald Trump announced his administration’s support for “second step legislation,” which generally professes to seek “successful reentry and reduced unemployment for Americans with past criminal records.” Having seen the light illuminating the poll numbers, presidential candidate Joe Biden has pledged to “eliminate barriers keeping formerly incarcerated individuals from accessing public assistance such as SNAP, Pell Grants, and housing support.”

On Wednesday, October 23, Novick and Botstein, accompanied by two BPI graduates, Wesley Caines and Dyjuan Tatro, presided over a preview screening of College Behind Bars in the Morehouse School of Medicine auditorium, followed by a panel discussion moderated by WABE-FM’s Rose Scott. During the afternoon prior to the confab, Novick, Botstein, Caines, and Tatro discussed the documentary with Creative Loafing in an exclusive telephone interview.

Doug DeLoach: What has been the response to College Behind Bars?

Lynn Novick: The reception has been overwhelmingly positive regardless of the setting. We’ve been in city halls, governors’ offices, and on college campuses, and the energy from the audiences has been remarkable.

Dyjuan Tatro: At the launch meeting, Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, sent us off on the right foot. Basically, he said, “So much of what we’re used to seeing in the media around people in prison is derogatory and depressing. This is a story about hope. This is a story that inspires. It’s a different type of story about people who are incarcerated in this country.”

What sort of challenges did you face in the process of making the film?

Novick: The biggest challenge was the fact that we were watching and documenting a story, which was unfolding before our eyes over four or five years. We had to let the story happen first and then figure out how to tell it using four hundred hours of film, which was masterfully edited by Tricia Reidy.

The original idea was to follow people over time beginning with their acceptance into the Bard program through graduation. Of course, as things happened within each person’s story, we had to be flexible and follow things where they led us.

What sort of access did you have and how difficult was it to arrange?

Sarah Botstein: It took a long time to get access. Having said that, the New York State Department of Corrections and the State of New York really believe in higher education in prison and the BPI program in particular. They were supportive all along the way.

We were in a maximum security prison. We were always very mindful of what we could bring in, where we could and could not shoot, where we could be and not be depending on the time of day. It was unlike anything we had ever done before. We had to be extremely well-organized and coordinated. At any given moment, we were very much aware that the Department of Corrections or some other authority might decide they had given us enough access and that the production could end.

How did you coordinate the production schedule with activity inside the prisons where you were filming?

Wesley Caines: The prison days are structured into three modules: a.m., p.m., and evening. Those three modules include about three hours of out-of-cell time. Everything happens around that schedule: classes, programming, recreation, study hall. The filming took place within that ecosystem. Lynn, Sarah, and the crew would be in at seven in the morning, but access to the people inside who were studying only occurred during specific periods of about two to three hours each.

Tatro: We never knew when Lynn and Sarah were going to show up. They couldn’t call us to plan things. They would just show up with the cameras and take in what was happening in a spontaneous way.

How does the BPI admission process work for incarcerated students?

Caines: First and foremost, Bard is a liberal arts college. The global nature of a liberal arts education is intended to cultivate in the individual a sense of civic mindedness, a humanistic viewpoint, and critical thinking. The admission process for BPI is the same as if you walked up to the front door in Annandale and announced your intention to attend college. It’s an extremely competitive process. Each academic year, anywhere from 10-16 people are admitted out of between three and four hundred submitted applications.

How does someone who did poorly in school or might not have graduated from high school qualify for admission to BPI?

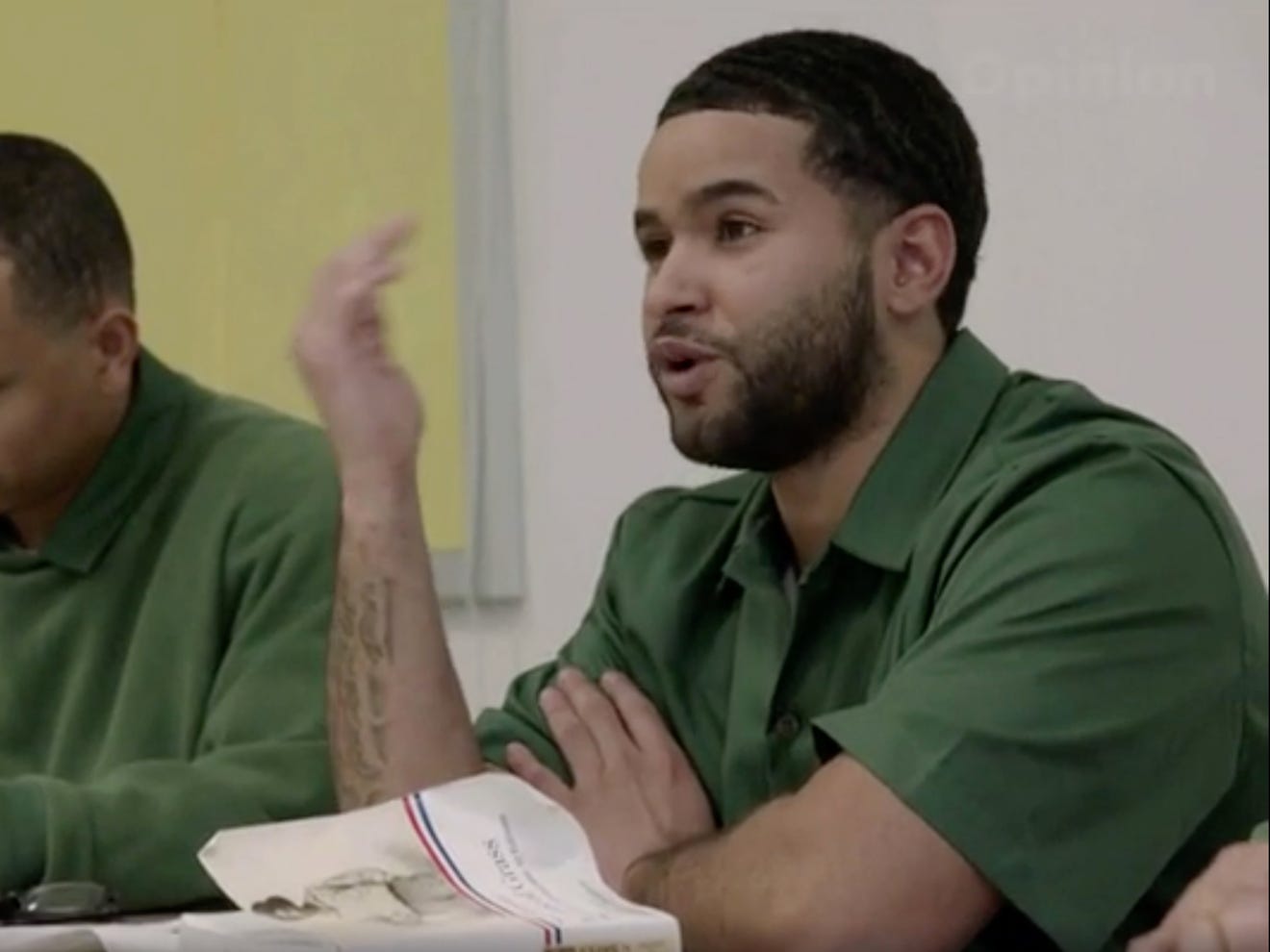

Tatro: When you take the essay-based entrance exam, you are given a series of prompts by authors you have never read before, people you are not familiar with, and they ask you to respond to those prompts in a way that is meaningful to you. What is amazing about this process is that the subjectivity in it allows people to be smart in different ways. It is not a formulaic, standardized test. It’s not a test intended to measure intelligence or academic ability or whether you know how to take a test. It’s designed to measure the student’s interest in and engagement with the subjects and ideas placed in front of them. When I took the exam, I did not know what to expect, and I sweated the whole time. Then I sweated, waiting for that letter to come. (Laughing)

What sort of reaction or response did you get from the prison population?

Caines: I was in the very first cohort of BPI students. My greatest support when I entered the program came from the people in prison with me. They saw in my admittance to the program and in my subsequent success the potential for their own success. They were very considerate and supportive of me and my fellow students. They were conscious of the noise level when we needed to study. They encouraged us when things got tough, when we questioned why we were enduring this academic rigor. They would say, “What’s wrong with you? I wish I could be there.” The impact of their support cannot be over-stated.

College Behind Bars is a remarkable documentary in its advocacy for expanding educational programs in the American prison system and, in particular, the effectiveness of the BPI model.

Tatro: While the film features all BPI students, it exemplifies the type of talent and genius that we have locked away in our prisons all across America. Rather than this film being a commercial for BPI, it is a film that demonstrates the transformative power of education and makes an argument for a greater need or access to education in this country in a very broad and general way.

Caines: Education is the vehicle in this documentary. BPI is the fuel in that vehicle. As a mirror of society, it reveals some of the choices we have intentionally made around mass incarceration. It shows the value of public education and the ways in which we grant access to quality education in and out of prison.

Tatro: Some people are going to watch this film and continue to disagree with what we’re doing. The film creates a space where both sides can come together and have a reasonable and balanced conversation around this issue.