One graduate, featured in a new PBS documentary, shares the ups and downs of earning a degree behind bars.

Courtesy of Skiff Mountain Films

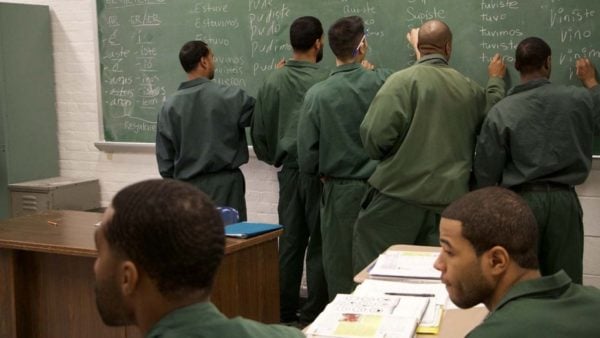

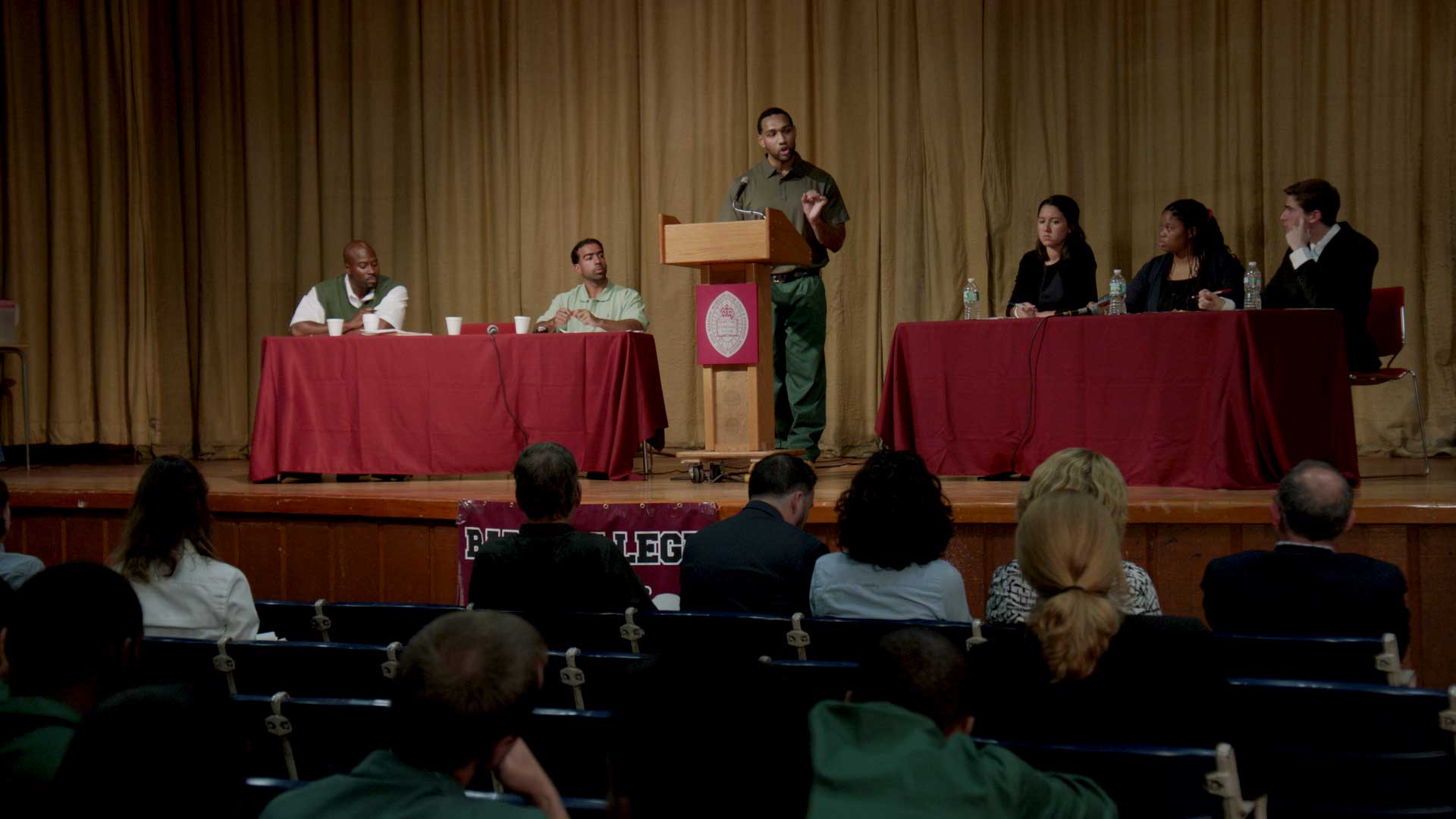

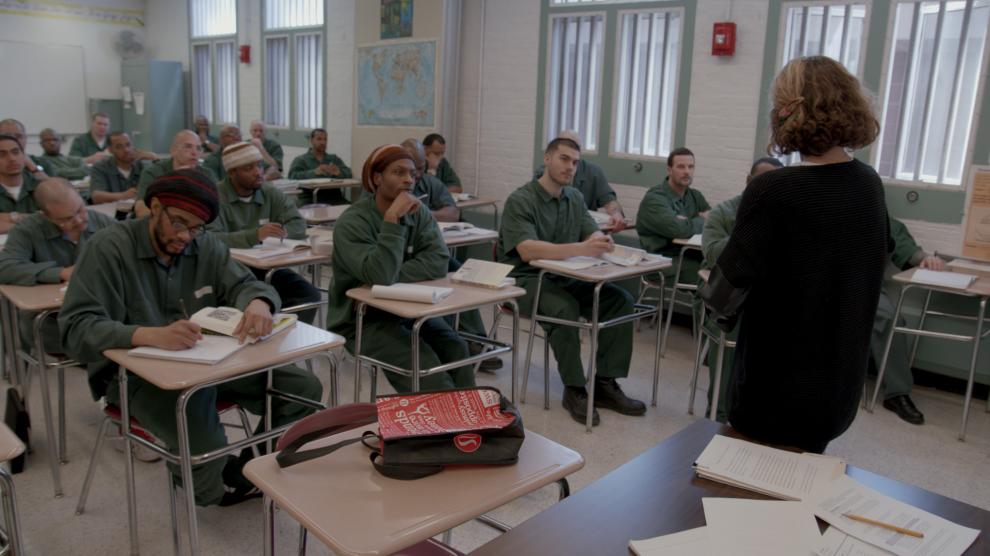

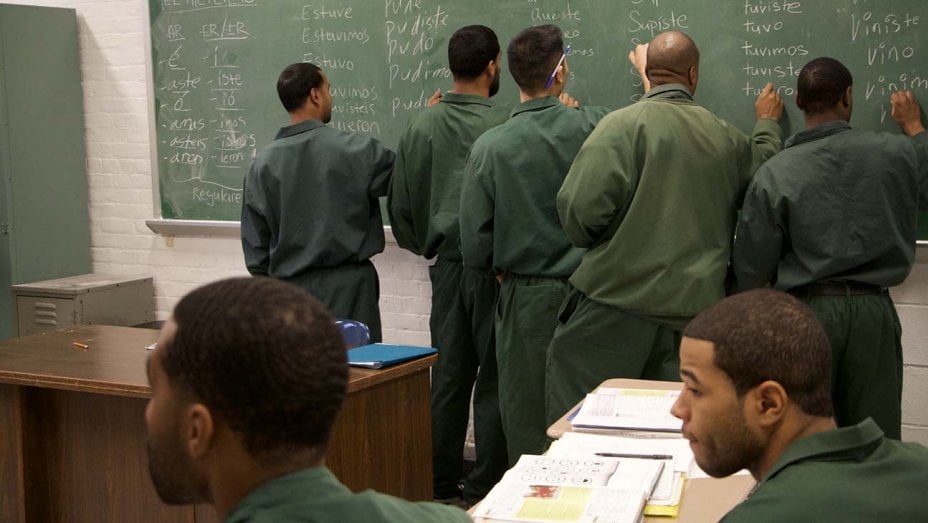

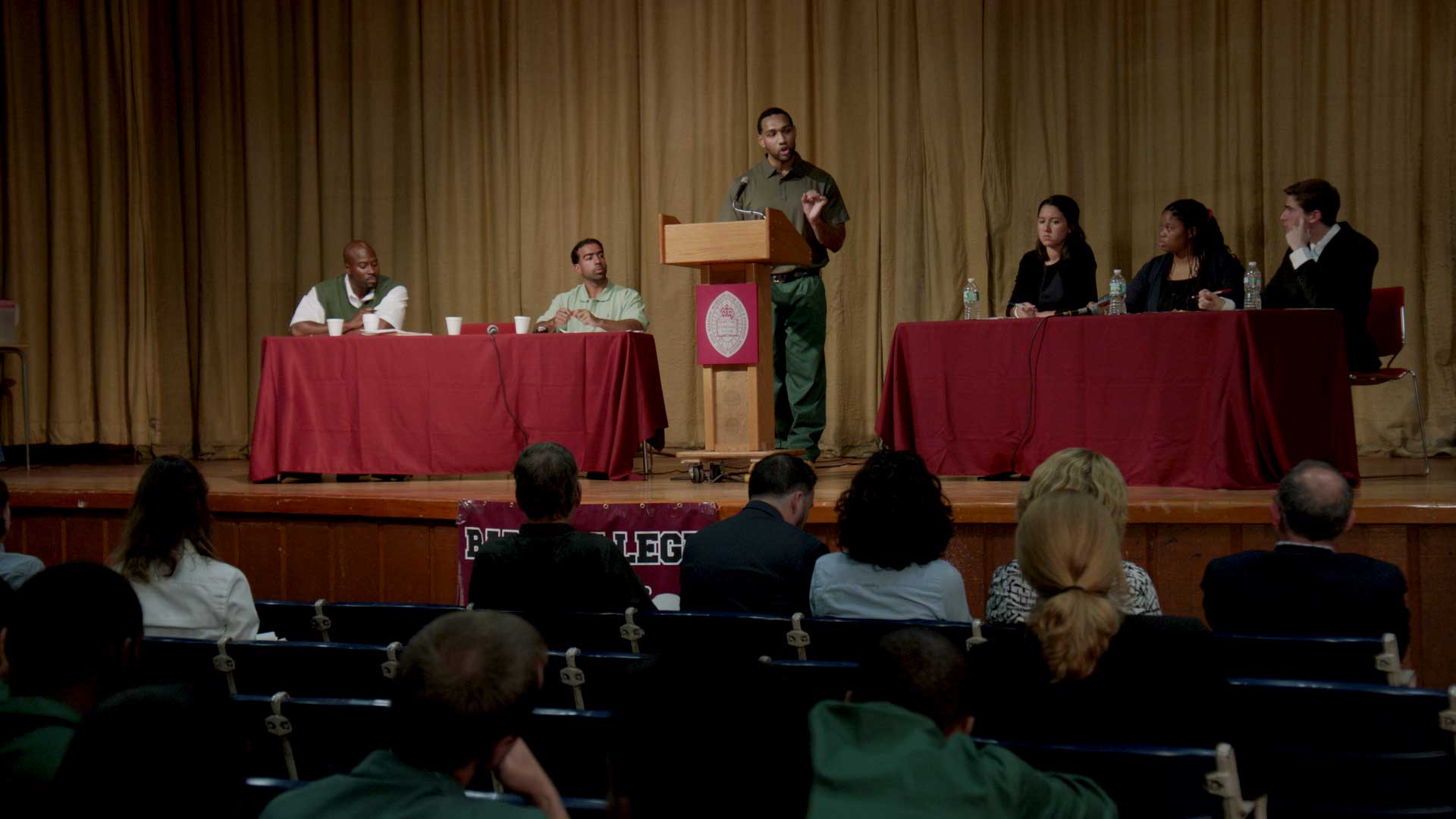

In the fall of 2015, a maximum-security prison in New York invited Harvard’s debate team to compete against a squad of three incarcerated men. The men, all convicted of violent crimes, knew they faced tough odds: Unlike their Harvard opponents, they could not use the internet to study the topic in advance. But the prisoners were declared the winners, and the crowd, including dozens of other incarcerated men in green jumpsuits, burst into applause.

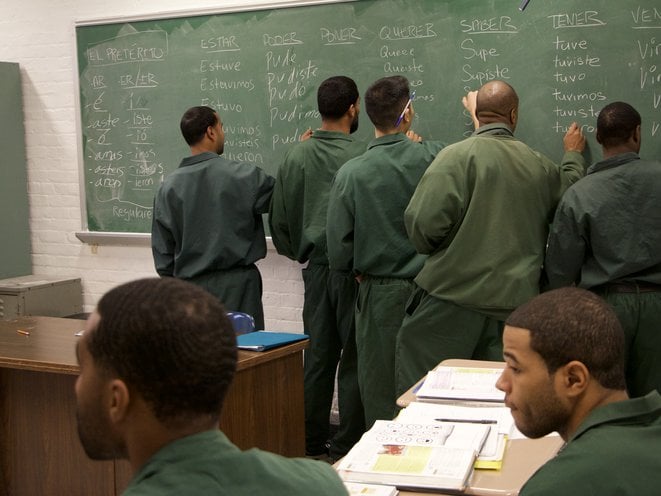

The incarcerated debaters at Eastern New York Correctional Facility were students themselves, part of an undergraduate program run by Bard College. The Bard Prison Initiative gives a small group of prisoners access to the same professors and curriculum offered to students on the regular liberal arts campus, allowing them to earn bachelor’s degrees. “BPI is a simple experiment,” Max Kenner, the program’s founder, says in College Behind Bars, a new documentary series directed by Lynn Novick, produced by Sarah Botstein, and executive produced by Ken Burns. “What happens when we provide the kinds of education that are typically in the US only afforded to the wealthy or lucky or rich, to others?”

What happens is more than just beating Harvard (or Cambridge) at debate. “We were blown away by the seriousness and intellectual sophistication and curiosity and the focus and collegiality and the way the students talked with us and to each other and raised really profound challenging questions that we had never been asked,” says Novick, who herself taught a Bard class about film before beginning the documentary. Graduates of the program are also much less likely to commit other crimes later. Only 4 percent of them have wound up in prison again, compared with about 40 percent of other New York prisoners.

If only more people could take advantage of the opportunity. Prison college programs used to be fairly common, but the 1994 crime bill written by Joe Biden and signed by Bill Clinton gutted federal funding for them. By 2001, when the Bard program began, only three other programs in New York offered higher education behind bars. Today, the documentary series shows that less than 2 percent of incarcerated people in the state’s prisons have access to higher education.

This week, I caught up with Sebastian Yoon, one of the students portrayed in the film. Incarcerated at the age of 16, he spent the first part of a 15-year sentence sweeping floors and wishing he could go off to college like his friends on the outside. At one point, he became so desperate he tried to kill himself. But the Bard program changed his outlook, and he threw himself into pursuing a degree in social studies. In one of the final segments of the series, he holds back tears after receiving an A on his senior thesis. “I want to go home and I want to look back at prison and say, ‘Prison was terrible, I never want to go back, but I learned something,’” he says afterward. “That is where transformation happens. That is what stops people from coming back to prison.”

Yoon was recently released. Here, he shares what it was like to go through Bard, the challenges of studying in a cell, and how a college program transformed the maximum-security prison where he lived.

Can you tell me a little about what your life was like growing up, and how you arrived at Eastern Correctional Facility?

I grew up without a mother, who left me when I was five. My father and my two siblings, we were together, and then I went to Korea for about two years when I was five. We came back to Flushing, Queens, and moved to Long Island when I was 10, and it was there that I found myself being one of few Asians in the entire school. I faced a lot of discrimination and racism. I didn’t know how to respond; all I could do was go home and pretty much cry. There was one time when I just snapped and reacted violently. From then on, I realized people stopped bothering you when you used force. I started hanging out in the streets, where I found a sense of empowerment. One night, me and my friends were hanging out at a karaoke bar, and a fight erupted, which wasn’t unusual for us. But this case obviously changed my life: At the age of 16, I was sentenced to 15 years for manslaughter in the first degree, as an adult. Because at the time, teenagers were still charged as adults in New York state. And then I landed at Eastern, five years after I was incarcerated.

Do you remember what your first day of class was like and how you felt?

When I first started class, I was very skeptical. I mean, I was interested and excited to be a part of it, and to have gotten accepted, but I was skeptical. Because generally programs within prisons are dumbed down, and nobody cares, not even the people who are teaching

Where would you study?

Most of my work happened in my cell late at night. Usually people start going to sleep at 11, but for us college students, sleep time was usually around 3 a.m., because the quietest time to study was after midnight. You don’t want to leave the lights on in the cell because it’s an open cell and it would bother people. So we would just turn on the lamps and read for hours on end and write essays. When you look out the window, the cells that you see with the lamps reflecting, they were usually college students.

Sebastian Yoon, Skiff Mountain Films

The film mentions how studying would get interrupted regularly for the count—when all the guys would have to go back to their cells to be counted by correctional officers. What were some of the other challenges that made it hard to be a student in prison?

Just being a prisoner, that in itself was probably the biggest struggle. No matter how hard you try to be a student, you are first and foremost a prisoner. The only way to fight it was to just get lost in the ideas and the books and discussions.

Without access to the internet, how would you do research?

Most of our research came through books. But we did have a non-online internet, called JSTOR. So we would type up a subject title, and we would see only the titles of the articles. Based on the titles, we could submit request forms, and there is a faculty member for BPI who, along with a team of Bard college students on [the main Bard campus], would print these papers out and bring them into the prison.

In the series, one student talks about how he was put into solitary confinement after writing a story for homework that included characters who swore during the dialogue. Were there other examples of students being punished for doing their work?

Not for doing homework, per se. But I’ve seen some instances where students got a ticket for having passed the book limit in their cells. In New York, I think the max is 15 books per cell. In a given semester, if you’re taking four to five classes, you’re going to receive more than 20 books. And you have to also include the personal books you have. Some officers are understanding, but there are some officers who would give you a ticket. Something like that was very frustrating. But what can we do? We took the risk. Books were more important.

Some of the guys in the documentary describe the Bard program as a way to escape mentally from the confines of prison, and one says it’s a sort of an “oasis…in the desert.” Is that how you saw it?

Well for me, I have to say that this program gave me life in the literal sense. Because when I first went to prison, I tried to commit suicide upon receiving 15 years. And I was desperate to find a reason to live. I was desperate for hope, because all I could imagine was upon being released that nobody would ever give me an opportunity because I’m a convicted criminal, and they would see me as a 16-year-old who committed an act—not define me as a person who committed a bad act, but define me as a bad person. In a place like prison, once you’re given even a glimmer of hope, you’re just going to latch onto it. And higher education materialized in a form of hope. And I was just gung-ho all the way. Nothing else mattered.

I used to tell my dad that finishing my senior thesis comes before being released. Like I wanted to finish that paper, that’s how important it was to me.

What was your senior paper about?

About how Koreans living in Korea and Korean Americans here look back on Japanese colonialism, which happened in the 20th century in Korea, and how they used that history to define their identities.

How were you spending most of your time before you decided to apply for BPI?

In the beginning, I swept and mopped the school floors. After that I went to work as a cook in the officers’ mess hall. So instead of making food for the inmates, I made food for the officers.

I was 21 at the time I was accepted into BPI. During that time, my friends who were outside would tell me about what they were doing in college, what kind of courses they were taking. I felt a deep sense of shame and despair thinking that while my friends were doing what every 20-year-old should be doing, I’m sitting here staring at my wall for hours on end. And I’m making no improvements for my life, and my prospects for the future weren’t getting any brighter.

Bard Prison Initiative (BPI) Debate Union defeats Harvard University in September 2015. Photo: Skiff Mountain Films

Some correctional officers never got a college degree themselves. Did this ever lead to tension with students who were pursuing their degree while they were incarcerated?

Some officers would say something like, “Just because you’re getting an education don’t think you’re better than me, or don’t think you’re smarter than me.” But there were also officers who encouraged us. It would really make my day whenever an officer searching my cell would ask about a paper that was sitting at my desk. “What are you learning now? I hope you guys graduate soon. I wish I could be there. If I could I will.” That was very encouraging for all of us.

Can you describe what graduation was like for you?

Oh, graduation was the highlight of my incarceration. It was a time when all the hard work that we’d put in was finally showcased. It was a testament to the fact that despite the difficulties, despite the hopelessness, we’d accomplished something. For my father, that became a talking point. As a parent, I guess when you’re having conversations with someone, it’s difficult to say, “My son or daughter is in prison.” Getting my degree, my dad could talk about me with a sense of pride, not in shame. He would say, “My son is incarcerated, but he’s getting a college education.” He was very proud that day.

Was there a particular book or class that made a big impression or changed your worldview?

My favorite class was called Cosmopolitanism. We talked about what it would like to have world citizenship, whereby our identities are not limited by nationalities, but where we are global members of the world. It taught me what it meant to have civic duty and to have civic virtues. I thought civic duties was limited to obeying laws, but that changed, and I realized that being a democratic person requires one to actively participate in the political process. I think it carries with me even up to this day. I’m constantly reading the news. I want to know what’s going on not only in the US, but in the world. And I want to be part of a change. And I’m gonna vote, which is something we couldn’t do in prison.

What are some of the ways that this Bard program changed Eastern as a facility?

It changes the atmosphere. If you ever visited, you would not see anything similar to what you would see in Hollywood shows or these documentaries that like to show prisoners acting irrationally and violently all the time. You would see incarcerated people walking around with textbooks in the yard, having conversations about philosophy and Plato. It pervades throughout the general population, the people who are not in the program: When they see us having a discussion, often they would come over and ask what we were talking about. The next thing we know, they were part of the conversation and we were able to teach them, but also we were able to listen to them. Which makes them feel like they want to continue this kind of thing and join BPI also.

When did you leave prison, and where are you now?

I was released from prison in March. I’m currently working as a program specialist with the Democracy Fund at Open Society Foundations, which is the second-biggest philanthropic organization in the world. We provide grants and support to other organizations and individuals who are committed to social justice reform work. I’m still in Long Island, but I work in Manhattan.

I live with my family, and it’s great. I’m helping to pay the mortgage, I’m able to do familial duties, to help my little sister with her homework. She’s in high school right now. She’s actually 16, which is the age I went to prison. Just looking at her reminds me how young I was. Because she seems like a baby to me. But yeah, life is really interesting, and I’m very optimistic for my future. And just being part of an organization that is about helping others, especially those who are marginalized, I mean, I wake up feeling really good about the coming day.

The series College Behind Bars aired on PBS on November 25 and 26 and is now available for free streaming on PBS.org through the end of January.