When College Behind Bars premiered four years ago on PBS and later moved to Netflix, it served as an introduction for many people to learn about college-in-prison. Since the film’s airing, there have been many policy wins for the field of college education in… Read More

BPI Blog

Category: College Behind Bars

BPI and College Behind Bars in The Appeal

The Appeal featured several segments about BPI in two Justice in America podcast episodes, as well as an op-ed. Check out more details below:

4/22/2019

Justice in America Episode 29: Schools in Prison

Josie Duffy Rice and co-host Derecka Purnell are joined by Dyjuan Tatro ’18 and Wesley Caines ’09 along with filmmakers Lynn Novick and Sarah Botstein to talk about education in prisons, the Bard Prison Initiative, and the documentary College Behind Bars.

4/29/2019

Justice in America Episode 30: A Conversation with Rodney Spivey-Jones and Max Kenner

In this episode, Josie Duffy Rice and her producer, Florence Barrau-Adams, travel to Fishkill Correctional Facility in Beacon, New York, to interview Rodney Spivey-Jones ’17 and Max Kenner ’01 about the Bard Prison Initiative and Bard College.

4/29/2019

Op-Ed – College Programs in Prison Show the Value of Educating Every American

Prisons, BPI graduate Rodney-Spivey Jones ’17 writes, should be institutions of learning, not ‘wastelands’ that willfully overlook human potential.

College Behind Bars review – how education can unlock prisoners’ potential

This film following students of the Bard Prison Initiative is a tribute to their ambition and endeavour – and an indictment of the absence of funding for such programmes

It should not be strange to hear prisoners talk about The Oresteia or Moby-Dick or eukaryotic cell structure – but it is. If it were not, BBC Four’s two-part Storyville documentary College Behind Bars would be neither interesting nor necessary. As things stand, it is both of these things, intensely.

Directed by Lynn Novick and executive-produced by Ken Burns (maker of the celebrated 1990 series The Civil War and many others, including last year’s Country Music), it follows several prisoners of New York state’s Eastern Correctional Facility – a maximum-security prison for men – and one at Taconic Correctional Facility, a medium-security prison for women. All of them are working towards a college degree under Bard College’s Bard Prison Initiative (BPI).

In the words of Max Kenner, its founder and executive director, the BPI “is a very simple experiment: what happens when we provide the kind of education that traditionally in the US is only provided to lucky, privileged, rich people to others?”

The BPI provides courses for associate degrees (between a high school diploma and a bachelor’s degree) and bachelor’s degrees inside six New York prisons, using the same curriculum as it does on the outside. It brings the same academic rigour, standards and expectation of commitment and engagement to its imprisoned students as it does to the rest.

The programme is one of the last survivors of Bill Clinton’s notorious 1994 crime bill, which eliminated federal aid for higher education in jails. After a brief, golden period of consensus that equipping prisoners with skills and knowledge was a good, practical and moral use of taxpayer dollars, the issue had become a political lightning rod. The president gave in. “We tried to convince the powers that be that this was a shortsighted decision,” says Anthony Annucci, the acting commissioner for New York’s department of corrections, “but we couldn’t compete with the 20-second soundbite.” A recidivism rate among BPI graduates of 4%, compared with the usual 50%, did nothing to change anyone’s mind.

College Behind Bars remains – especially in the first episode – admirably focused on the practicalities of prison life and prison programmes. It unpicks and dispels the myth that prisoners’ time is their own, to use or waste as they wish, and with it the idea that inmates succeed on educational programmes because they have no distractions. The headcount – which drags prisoners back to their cells five times a day – is disruptive enough, but the constant noise and unrest means that a lot of the students work from late at night until early in the morning; it is the only time that they can trust they won’t be interrupted.

Rule infractions can lead to solitary confinement and massive disruption to their academic progress. These happen often because there are many rules, and because immersing yourself in The Oresteia does not automatically or immediately make you a “model prisoner”. Nor does it protect you from injustice. One student, Rodney Spivey-Jones, nearly loses everything when a guard takes exception to the language used in one of his short stories and deems it a punishable offence.

Every prisoner here comes with a wealth of compelling backstory, but it is a tribute to the discipline and focus of the film-makers that only a few are related in full. Sebastian Yoon’s account of parental abandonment and poverty is enough to stand for all. Taconic inmate Shawnta Montgomery’s account of an upbringing and life that brought about the death of her young daughter outlines a path that is surely common to many. It is enough to evoke the difference between their lives and “normal” lives without overwhelming or numbing the viewer with a welter of miseries and narratives that become indistinguishable.

It also allows the film’s focus to remain on the educational programme and its effects. Heartfelt testimonies from current and past participants abound about the internal transformations wrought. “We become civic beings,” says Woon. “It’s changing fundamentally the way I think, behave and interact with people,” says Dyjuan Tatro (the eukaryotic expert). Giovannie Hernandez says a friend forced him to apply for the programme after Hernandez got his GED (an alternative to the high school diploma) on Rikers Island. “Probably the kindest, most loving thing anyone’s ever done for me,” he says.

The BPI is funded entirely by donations. Studies reckon that every $1 invested in higher education in prison saves the public $5 overall. Taxpayer dollars are not at work.

Op-Ed – College Programs in Prison Show the Value of Educating Every American

Prisons, one graduate writes, should be institutions of learning, not ‘wastelands’ that willfully overlook human potential.

by Rodney-Spivey Jones ’17

Opinion Contributor

A few weeks ago, I was sitting at a library table with several other tutors, discussing strategies for supporting first-year Bard College students. One colleague suggested that we organize a workshop to introduce students to creative writing. Another said we should teach sentence structure and paragraph cohesion. Mentally, I took a step back for a moment and really looked: Here we were, 10 men surrounded by books and the tapping of computer keys discussing tutoring strategies inside a New York state prison.

I have been incarcerated since I was 19—nearly 18 years. I know that many Americans are convinced that the conditions in which incarcerated men and women like me live—the stifling heat and the frigid cold, the enforced idleness, the abuse that sometimes leads to death—are well-deserved, that all of this is justice. If prisons are supposed to be finely tuned instruments of punishment, they succeed 100 percent of the time.

But if prisons are meant to rehabilitate, they are failing. They destroy mental health and crush dignity, right before propelling us back out into the free world—broken and disillusioned. Indeed, the national recidivism rate is 83 percent; in New York, more than 40 percent of people released from prison are back in prison within three years. The doors to prison are well-worn turnstiles and everyone pays the price—$50 billion per year—over and over again.

As a country we could try to imagine a society that throws no one away, an America determined to educate every one of its citizens regardless of criminal history. Prisons—if they must exist at all—should be institutions of learning, where incarcerated citizens consider the importance of community building and civic engagement. They should be universities, not vast wastelands of soul-crushing misery and discarded human potential.

“Education is the purest form of rehabilitation,” Anthony J. Annucci, acting commissioner of the New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision, has rightly observed. He was referring to programs like the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI), through which I earned a Bard College bachelor’s degree. Many who share his view rely on recidivism rates to measure success. Reduced recidivism means improved public safety. Among BPI alumni the recidivism rate is just 2 percent, a fraction of the state average.

However, the value of a rigorous liberal arts education is greater than reduced recidivism and tax savings, greater than getting jobs and staying out of trouble. In the classroom we begin the heavy lifting of self-examination, considering our place within and effect on the world. Struggling to parse difficult texts gives us an opportunity to explore the human condition, and in the process examine layers of our own humanity. In the space that colleges create within prisons we begin to appreciate how our actions, and our absences, affect our communities, and we take these lessons with us.

After leaving prison, many BPI alumni join nonprofit organizations, participate in local politics, and, to the extent possible, repair the harm we’ve caused. Many of us know that we owe a debt impossible to discharge, yet we attempt to do so because a liberal arts education cultivates and nourishes a sense of accountability and community.

Believing that incarcerated citizens constitute a separate and distinct population can give the country only a false sense of comfort and security. No matter how hard we try, no matter how justified we feel, America cannot amputate more than 2.2 million people from the social body. Ninety-five percent of us will return; if nothing changes, most of us will return ill-prepared to make meaningful contributions to society.

There is a clear choice.

America can have wastelands of discarded human potential, and all of the “success” that produces—high incarceration rates, more crime, and more hurt people—or institutions that promote intellectual growth and civic engagement. We cannot have both.

Rodney Spivey-Jones received his bachelor’s degree from Bard College in 2017 through the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI) and is featured in the PBS documentary series “College Behind Bars.” He is incarcerated at Fishkill Correctional Facility in Beacon, New York

Justice in America Episode 29: Schools in Prison

Josie Duffy Rice and co-host Derecka Purnell are joined by Dyjuan Tatro and Wesley Caines to talk about education in prisons.

On this episode of Justice in America, Josie Duffy Rice and her co-host Derecka Purnell talk about education in prisons. They’ll discuss the impact of having access to education, the dire lack of available programming, and what happened to prison education after the 1994 crime bill. They’re joined by Dyjuan Tatro and Wesley Caines, alumni of the Bard Prison Initiative. The Bard Prison Initiative is a college program offered through Bard College in six New York State prisons. It’s also the subject of a critically acclaimed new documentary series on PBS, called College Behind Bars.

Listen to podcasts below:

Episode 29: Schools in Prison

Read the full transcript here.

Dyjuan Tatro and Wes Caines’ Book Recommendations

Dyjuan Tatro’s Guest Book recommendation: Until We Reckon: Violence, Mass Incarceration, and a Road to Repair by Danielle Sered

Wes Caines’ Guest Book recommendation: Outliers: The Story of Success by Malcolm Gladwell

Justice in America is available on Apple Podcasts, Soundcloud, Sticher, GooglePlay Music, Spotify, and LibSyn RSS.

Bonus: Interviewing the creators of College Behind Bars

In this bonus episode, Josie Duffy Rice and her co-host Derecka Purnell talk to Lynn Novick and Sarah Botstein, the creators of College Behind Bars. College Behind Bars, which was directed by Novick and produced by Botstein, is a four-episode documentary series about the Bard Prison Initiative, one of the most innovative and challenging prison education programs in the country. Josie and Derecka talk to Sarah and Lynn about the years they spent making the film, what they learned, and the future of prison education in America.

Read the full transcript here.

Additional Resources copy and links:

To watch College Behind Bars, find out more at PBS. You can also watch it on Netflix.

More information about BPI can be found here.

The Prison Policy Initiative has a wealth of resources on education in prisons.

For more information about programs that currently exist, check out the Prison Studies Project, which can be found here.

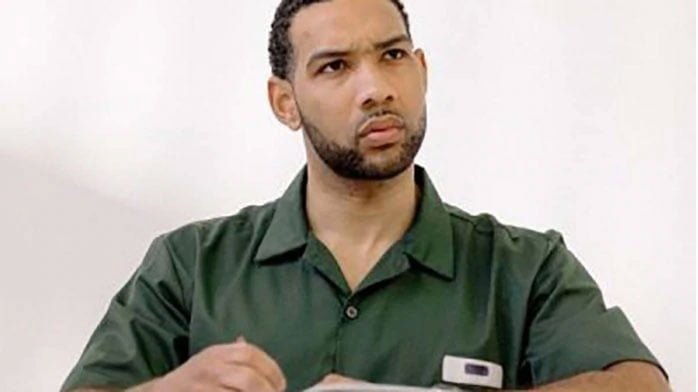

Dyjuan Tatro of ‘College Behind Bars’ talks education reform for prisons

Dyjuan Tatro, 31, has served 11 years incarcerated. (Photo courtesy of Florentine Films)

More often than not, incarcerated persons are viewed negatively in society. Ken Burns and Lynn Novick‘s documentary, College Behind Bars, is striving to change that narrative.

“Inside the walls of a classroom, you escape the walls of a cell — and you become an individual again,” says Shawnta Montgomery, speaking at the 16th commencement of the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI), in the documentary.

College Behind Bars first premiered Nov. 25, 2019 on PBS and has since then become popular among Netflix audiences. The four-part series follows the journey of men and women incarcerated in maximum and medium-security prisons across New York state over the span of four years.

Photo: Netflix

The documentary shadows them as they pursue college-accredited degrees through BPI, one of the most challenging prison education programs in the nation.

To further discuss College Behind Bars and the advocacy for college access in all prisons, theGrio spoke with Dyjuan Tatro, a formerly incarcerated student of BPI who appears in the documentary. Tatro completed his incarceration in 2017.

“One thing I am grateful for about College Behind Bars is that it complicates the narrative we see around incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people like myself,” Tatro tells theGrio.

“The filmmakers decided to introduce you to the subjects as people before you found out what they were incarcerated for. The film brings people to acknowledge the humanity of others. We view someone who went to prison for something and we say that’s who they are.”

Before incarceration, Tatro says going to college was not a part of his solid plans for the future.

“I look back, and now realize that I had this vague sense that college was something that I should have been striving for. I had no real expectations that it was something that I would actually ever do,” Tatro says.

“I vividly remember sitting in Five Points Correctional Facility and seeing a 60-minute segment on the Bard Prison Initiative come on, and there were these amazingly-smart men who were in prison just like me, wearing green like me, embarked on this rigorous educational endeavor. At that moment I decided, that was what I was going to do.”

Founded in 1999, BPI is now present in six New York State prisons. Prospective students undergo a meticulous admissions process and then enroll full-time in the same classes that they would take on Bard College’s main campus.

BPI students receive the exact education from college professors in seminar settings and are still held to the same academic expectations as Bard students outside of prison. BPI students can pursue associate and bachelor’s degrees.

College Behind Bars was filmed in real-time as students carried out their prison terms.

Students of the Bard Prison initiative filming for College Behind Bars. Photo courtesy of Florentine Films

“There was a lot of uncertainty and pressure going into Bard. Getting into BPI is a competitive process and you don’t know what to expect,” Tatro reveals.

“I found the course material to be really challenging, and that was intimidating but I was never scared to walk into that classroom because for the first time in my life I was learning what a professor was. But it built my intellectual capacity to a level where I could keep meeting the Bard standards.”

Tatro touched on what life was like being a student while incarcerated, amongst the rest of the prison population.

“There’s a popular joke that people, like myself, who received an education in prison had all of the time in the world and that’s why it was easy for us. The reality is its the total opposite,” he explains. “Prison is not conducive to receiving an education. Everything about prison impedes your education.

Photo: Netflix

“My professors assigned me 43 books for example, and I’m only allowed to have 35 books in my cell at one time. It’s those kinds of practical tensions in getting an education that you have to grapple with, on a day to day basis,” Tatro says.

“You’re on a noisy cell block and you can’t tell everyone to be quiet or shut up, you can be in class and at any given moment sent back to your cell because of a shutdown and your professor can’t be let back in. One thing I had to do was find it in myself to focus in such a way that despite what was happening, I still received a rigorous education.”

BPI offers a string of electives for students to participate in such as the debate team, which Tatro was a part of. Since 2013, the BPI Debate Union has met weekly with the college faculty coach to prepare and practice for intercollegiate debate competitions with colleges and universities including West Point, Harvard, Brown, The University of Vermont, and the historically Black Morehouse College.

“It was such a great moment for us as debaters; as students; as ambassadors of the power of college in prison,” Tatro says. “That win against Harvard was so profound and it went viral. Sitting in prison and seeing the media pick up the story and getting letters and calls from friends, it inspired so many people. It also moved the general public to think differently about who incarcerated people are, and what they are capable of.”

Tatro spoke about the assumptions that his success story, portrayed through the documentary, has made people believe that prison was a positive experience for him.

“Getting an education in prison was less than ideal … I did not go to prison to get an education,” Tatro said. “I would have rathered gone to college without having ever gone to prison. But the reality is if I never went to prison and BPI didn’t exist, I’d probably never have gotten a college education.”

“Our country spends $80 billion a year on mass incarceration. That’s enough money to make tuition at all of our public colleges and universities free,” he continued. “There’s an assumption that prison did something for me — no. Bard College did something for me.”

Dyjuan Tatro, 33, Government Affairs and Advancement Officer for BPI. Photo courtesy of Dyjuan Tatro

A 2016 study by the RAND Corporation found that inmates who participated in educational programs like BPI were up to 43% less likely to have recidivism. That same study found that for every dollar invested into correctional education, nearly five dollars is saved in reincarceration costs over three years. Since filming College Behind Bars, Tatro has gone on to become the BPI Government Affairs and Advancement officer, a prison reform advocate, and a political consultant.

Tatro and BPI continue to take strides to make education accessible for more prisons nationwide, although, there are still prominent obstacles in the way of that goal. Funding seems to be the main reason behind slow progress in gaining adequate education in more prisons, according to Tatro. In retrospect, the 1994 Clinton Crime Bill ended inmates’ eligibility for federal Pell grants during the era of “tough on crime” policies. Because of that, many education programs in prisons were stripped overnight.

“For the last 20 years, BPI has been an example of the power of education in prison. We have students who have faced 15-20 years and then gone onto Ph.D. programs at Yale, Columbia, and other Ivy League universities,” Tatro says. “What the students have done is lead by example.”

“Currently, we are working with Warner Brothers to turn the BPI vs. Harvard debate story into a movie,” Tatro mentioned. “We will continue to be out engaging around the film and lobbying on behalf of getting access to college in prison.”

College Behind Bars is available on Netflix now.

Founder of Famed Initiative to Provide Education for Prisoners Visits the Price of Business Show

According to Ken Burns, who is the force behind this important four part video series that originally appeared on PBS, “College Behind Bars, a four-part documentary film series, tells the story of a small group of incarcerated men and women struggling to earn college degrees and turn their lives around in one of the most rigorous and effective prison education programs in the United States – the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI).

“Shot over four years in maximum and medium security prisons in New York State, the four-hour film takes viewers on a stark and intimate journey into one of the most pressing issues of our time – our failure to provide meaningful rehabilitation for the over two million Americans living behind bars. Through the personal stories of the students and their families, the film reveals the transformative power of higher education and puts a human face on America’s criminal justice crisis. It raises questions we urgently need to address: What is prison for? Who has access to educational opportunity? Who among us is capable of academic excellence? How can we have justice without redemption?” See USA Daily Times article.

Interview with Max Kenner on The Price of Business

Recently Price visited with the founder and Executive director of the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI). According to BPI, “Max Kenner conceived of and created BPI as a student volunteer organization when he was an undergraduate at Bard College in 1999. After gaining the support of the College and cooperation of the New York State Department of Correctional Services, he has overseen the growth of the program into a credit-bearing and, subsequently, degree-granting program in 2001. In addition to organization management and program design for BPI, Kenner is responsible for fundraising and management of relations with New York State and the Department of Correctional Services.”

Listen to the Interview:

College Behind Bars with Max Kenner and Sebastian Yoon

The Bard Prison Initiative is a revolutionary program that provides a rigorous college education to men and women in prison. In one of our most power episodes ever, BPI’s founder Max Kenner and recent graduate Sebastian Yoon join Adam this week to discuss how lifechanging the program is, and how it proves that every person deserves an education, no matter the circumstances.

BPI Alumni Announce New IWT College Behind Bars Workshop for Teachers at UFT Film Event

BPI alumni Dyjuan Tatro and Giovannie Hernandez joined a United Federation of Teachers screening of College Behind Bars as part of UFT's Black History Month Film Series on February 27th and proudly announced to the audience of teachers that Bard College will be offering… Read More

College Behind Bars Coming to Holyoke Microcollege

Friday, March 20, 2020 1:30-3:30 p.m. Holyoke Library Community Room 250 Chestnut Street, Holyoke Please join us for a screening of highlights from the documentary film COLLEGE BEHIND BARS, about students in the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI), one of the most rigorous prison education programs in America. The screening… Read More