The movement for criminal justice reform in New York has made some progress lately. The Legislature eliminated cash bail for most low-level offenses and passed broad discovery and speedy trial reforms. The governor has begun to grant clemency, albeit in a limited manner. In New York City, the City Council has voted to close Rikers Island.

Yet so much more needs to be done.

To date, the criminal justice reform movement in New York has been focused on sending fewer people to prison and getting some people who should not be there out, but little is happening to equip people who are incarcerated for life back in their communities when they’re released.

The overwhelming majority of these individuals will be released from prison with only a bus ticket and $40 in their pocket. That’s it.

It should come as no surprise that 40% of them will be back in prison within three years. The rest will struggle to find housing, jobs and a place in society.

My story was different. On Aug. 10, 2017, I was released from prison after having served 12 years. I didn’t just have a bus ticket and $40; I was a Bard College student.

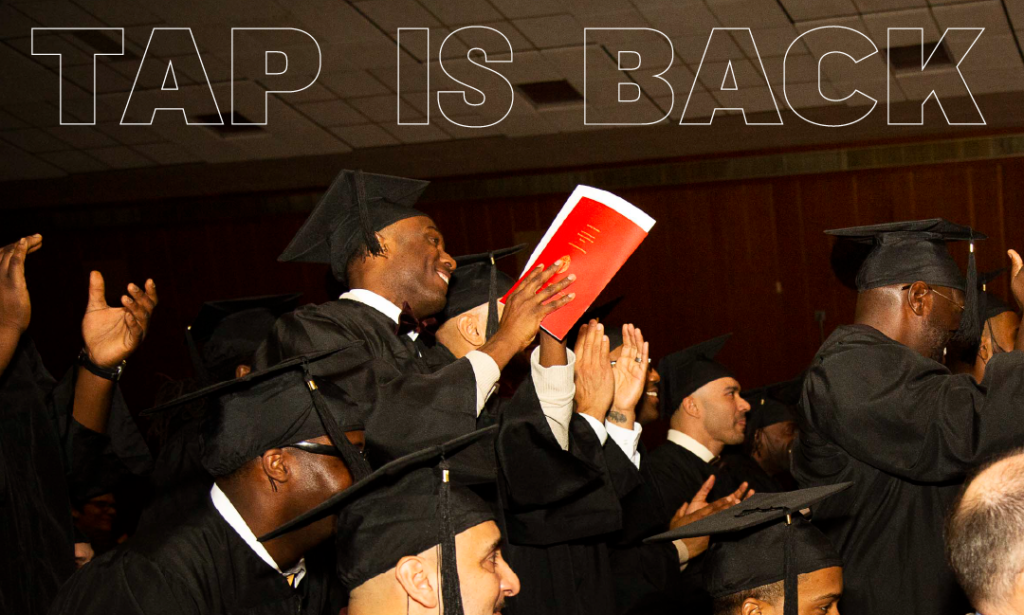

Two weeks later, I began taking advanced math courses and working on my senior project. By the following May, 41 weeks and one day later, I graduated from Bard College with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics. I walked across the stage on the college campus in Annandale-on-Hudson, and Bard President Leon Botstein handed me my diploma.

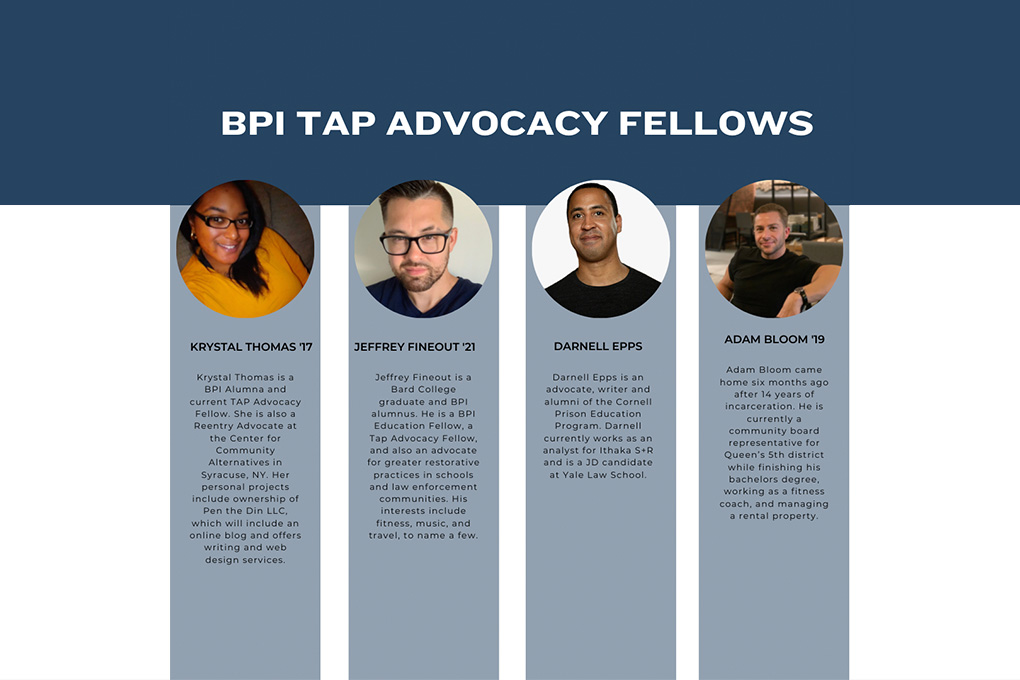

That summer, I went to work on Sean Patrick Maloney’s attorney general campaign as his criminal justice policy adviser. I then went on to be a project manager for a major software developer. Today, I am the government affairs officer at the Bard Prison Initiative.

What made these opportunities possible for me? A liberal arts education. I applied to BPI in 2013. I took the entrance exam, sat through the interview, and then sat in my cell each day hoping for an acceptance letter. It finally came. That moment forever altered the course of my life.

For the next four years, I worked harder than ever. I took a full course load, four or five classes each semester. My courses were rigorous and identical to those offered to students on Bard’s main campus. I joined the debate team. As a member of the debate team, my teammates and I defeated Harvard in 2015.

Unfortunately, most people incarcerated in New York State won’t have the same types of opportunities as I did, not while inside nor when they get out.

The 1994 Crime Bill ended federal Pell Grant eligibility for people in prison. Soon thereafter, New York, along with many other states, ended tuition assistance to incarcerated people. As a result, the number of college-in-prison programs offered nationally dropped from about 800 to fewer than 10.

Federal and state legislators ended these programs despite the fact that people who receive a college education in prison are the least likely to return. The recidivism rate for BPI alumni is only 4%, 10 times lower than the New York average.

New York State spends $69,000 a year to keep someone incarcerated. It costs BPI only $9,000 a year to educate its students. Comprehensive studies have shown that, for every dollar a state spends on higher education in prison, it saves at least four times that much on reincarceration costs.

Quite simply, college in prison saves us money. But it’s more than just a matter of dollars and cents. Providing educational opportunities in prison can turn something designed only to be punitive into something transformative, and that’s worth so much more to our communities and society as a whole. Yet, of the 46,000 people currently imprisoned across New York State, fewer than 900 have access to higher education right now.

If more incarcerated women and men had the same type of opportunity I had, who knows what they would achieve. I’m willing to bet that they would defy common expectations.

Tatro is government affairs officer for the Bard Prison Initiative.