Incarcerated students’ ability to access New York’s Tuition Assistance Program (TAP) has been restored in New York State after 26 years of a senseless and destructive ban. This victory is a long time in the making.

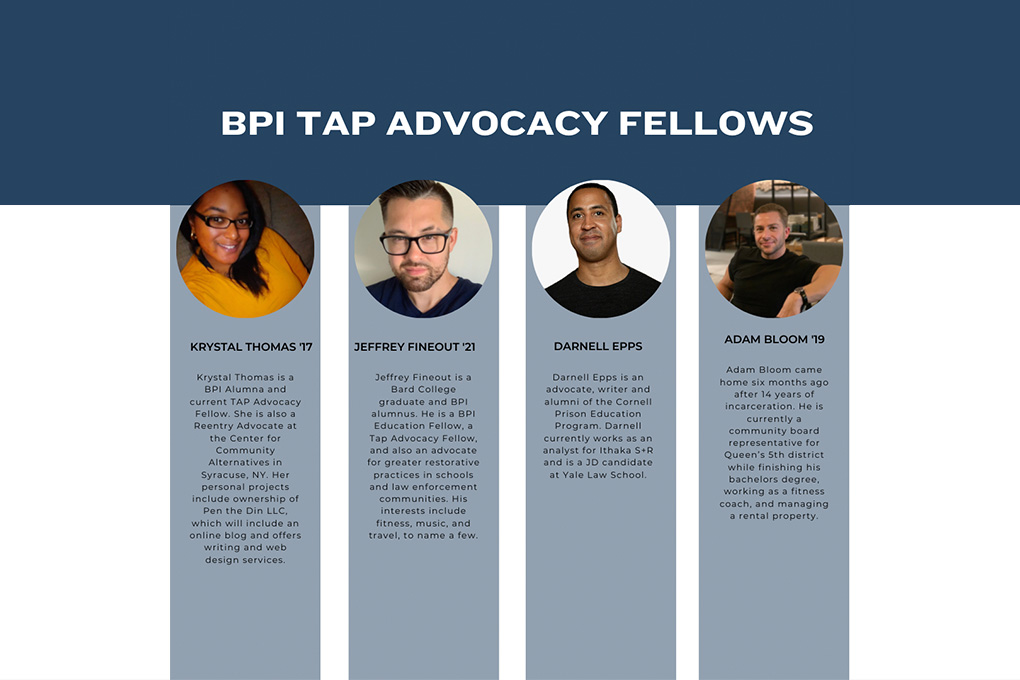

With BPI’s Senior Government Affairs Officer Dyjuan Tatro ’18 at the helm, we are proud to have joined together with our friends at College & Community Fellowship and with advocates, educators, alums, & directly impacted communities to see this through.

Because of the tremendous #TurnOnTheTAPNY coalition, there will once again be public funding for college-in-prison in New York State.

We celebrate this victory with the hope that TAP is a note in a larger symphony of long-overdue criminal justice overhauls in New York, part of a movement and not an exception to the needed change advocates have long fought for and are fighting to protect.

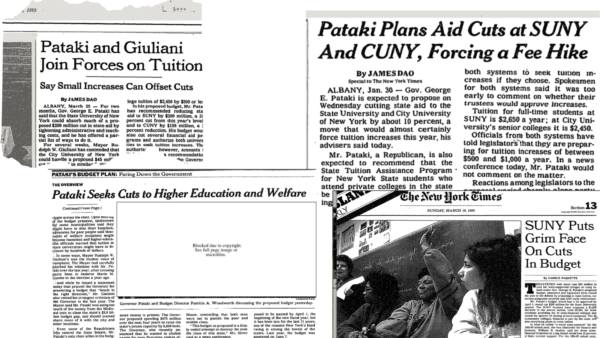

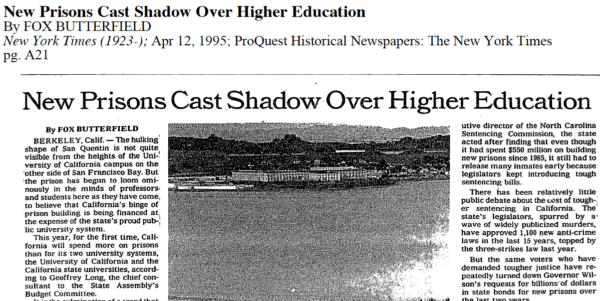

The 1995 TAP ban represented the apogee of cynical and punitive policy in the disastrous tough of crime era that created mass incarceration. While then-Governor George Pataki and New York lawmakers banned TAP in prison, they simultaneously gutted funding for public higher education in the state.

The move to expand prisons while making them worse, while also divesting from public education and community resources was a clear attack on Black and Brown and poor communities across New York, following national trends. It was racist, cruel, and shortsighted.

It was deeply symbolic in its messaging of whose lives mattered to the state, and whose did not. But it also had very material consequences. With the loss of public funding, colleges, previously common in nearly every prison in New York, were shuttered almost instantly.

BPI was created just after that moment, in the late 1990s when the memory of TAP was still fresh. When Bard undergraduates went into surrounding prisons in 1999 at the start of BPI, we encountered men and women who remembered what it had meant to have access to college, and also what it had meant to see it decimated. I remember seeing the film The Last Graduation, a documentary about Mercy College’s very last graduation at Sing Sing before the program shuttered in the spring of 1995 in the wake of the TAP ban, and the sense of urgency I felt about the idea of restoring access to college, even if only on a small scale.

In the 20+ years since BPI’s launch, we have worked to keep alive the memory of robust and meaningful college opportunity in prison. We have strived to create an example of what college could be in prison so that when funding and interest in this work returned, no one could say it was impossible.

It is fitting then, that TAP is being restored for people in prison once again alongside new support for SUNY and CUNY, an expansion of the size and scope of TAP grants more broadly, and in an era of landmark criminal justice reforms that we must now work to protect. 26 years after the TAP ban, the prison population in New York is half what it was at its height in the late 1990s, and movements led primarily by directly impacted communities, including BPI alumni, are helping the public to imagine a new paradigm for public policy that would address social and public safety needs through investments in community-based resources, including education, rather than police and punishment.

With the return of federal and state funding, college-in-prison, too, is poised for a new era but it’s crucial we get it right and also protect what this field has built over the years. New forces of exploitation and profiteering are sure to try to take advantage of this new era that public funding and technology make possible, with promises of scale too often in exchange for all the things that make college truly meaningful to students. The lessons of the 1990s tell us we have to be built to withstand shifting political winds. Public funding offers programs a crucial level of stability and will help new programs develop, but it is not enough. And we know now: it can be taken away at any time. We have to be prepared, and built, for longevity. But the old days of Pell and TAP– when colleges build programs organically as an effort to expand access and reach more students — also show us that widespread access to opportunity does not have to come at the cost of homogenizing and centralized systems as many in the worlds of policy and philanthropy are want to do in this moment. Now is the time to build sustainable access that represents the diversity and strengths of the best of the landscape of higher education: college that disrupts the status quo, not what fits most comfortably or neatly within the prison system.

BPI’s national work seeks to counter these trends by helping colleges of all kinds, everywhere, build their own college degree programs in prison to represent their own main campus degrees with integrity and depth as examples of inclusive excellence, first through program building via Bard’s Consortium for the Liberal Arts in Prison established in 2009, and more recently through the BPI Summer Residency for emerging practitioners now entering its 4th year. Together we can offer a redefinition of “scale” centered on radically democratizing access to the entire breadth of higher education: public and private, large research universities, small liberal arts schools, Catholic, vocational, HBCUs, and land-grant institutions, community colleges, and more; all doing what they do best. AA and BA degrees, and beyond.

In this new era, we look forward to many more educators and institutions joining us as we continue the work to expand college opportunity in and outside of prison that is as ambitious and optimistic as our students, and that honors the breadth and capacity of their imaginations. There’s never been a more crucial time to do this work.

Jessica Neptune ’02 is Director of National Engagement at the Bard Prison Initiative, a program she worked on in its funding years as an undergraduate at Bard College. She previously worked with the Obama Administration’s Federal Interagency Reentry Council as an American Council for Learned Societies Public Fellow. She holds a Ph.D. in American History from the University of Chicago. Her scholarship is on the making of the carceral state and the history of punishment in New York and nationally.