“College Behind Bars,” a new PBS documentary executive-produced by Ken Burns, shines a light on a program that every major university in America should be sponsoring

Courtesy of Skiff Mountain Films

By Jamil Smith

When you watch College Behind Bars, which began last night on PBS and concludes tonight, or any other documentary like it, please don’t say that it “humanizes” the people who are photographed. Because they’re people. Our society teaches us to consider folks like Dyjuan Tatro and Giovannie Hernandez, two of the film’s subjects, to be numbers or vermin or somehow less than us when they’re locked up, and they are considered to be little more than the property of a state or federal prison. But we have to remember that is a judgment that someone, or a system, has put upon them.

Also, we should remember that they’ll likely get out one day. What then?

“Ninety-five percent of people who are incarcerated will eventually get out,” Ken Burns, the executive producer of the documentary, told Rolling Stone. “And the question is, do we want them as contributing members of society, or do we want them having used prison as a different kind of school to hone criminal skills? If you’re spending $100 billion a year to maintain our prison system and it has a 75 percent recidivism rate, something is broken.”

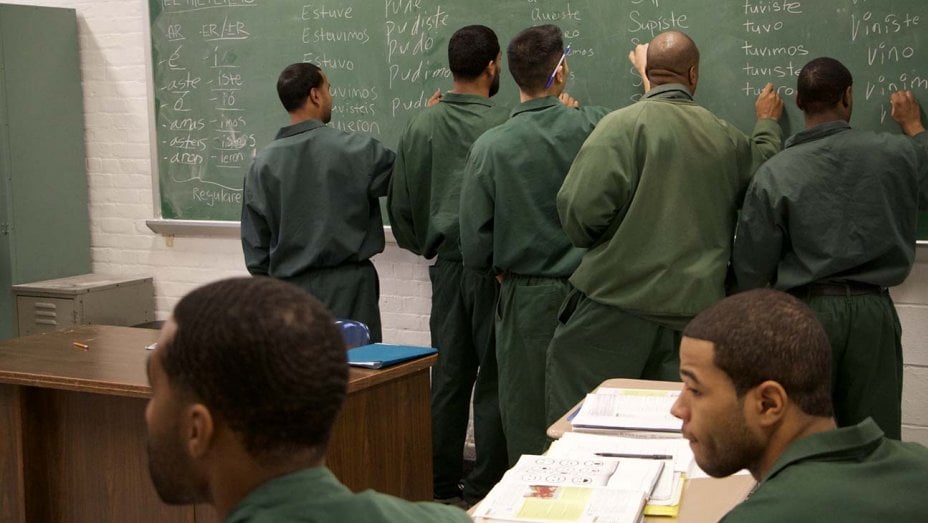

This is the question that the four-part film examines with a critical eye. Directed by Lynn Novick and produced by Sarah Botstein, College Behind Bars profiles the Bard Prison Initiative, a Bard College program that extends its curriculum and has awarded nearly 550 full degrees thus far to matriculated students in six New York State prisons.

“It was an enormous privilege to work on a film that was living, breathing American social history,” said Botstein. “The politics changed so drastically in the five years that we were filming and editing. When we started, people kind of would shrug and kind of lean in a little bit when we said we wanted to make a film about higher education in prison. And by the time we locked picture, everybody was really excited that we had.”

The hyper-awareness of issues revolving around incarceration, education, and race did not merely manifest on the outside. “You know, a lot of times, when we don’t have access to things we decide that they are not for us,” Tatro told me in a phone interview. He added that he had spent his entire life thinking he’d never go to college. “The opportunity was there for me to even dream of this possibility. Seeing black men, Latino men, men like me who came from the types of neighborhoods and went through the same types of bad schools that I did speaking Mandarin, doing higher-level mathematics, sitting down and having these complex political discussions — that, even before the coursework, had a really profound effect on my sense of identity.”

Tatro entered prison at the end of his teenage years and felt that he applied to BPI, one year into his 12-year sentence, because he had “nothing else better to do.” He would go on to become a member of the Bard debate team that defeated Harvard in a well-publicized 2015 matchup and is now working for BPI as a government-affairs and advancement officer.

Bard Prison Initiative (BPI) Debate Union defeats Harvard University in September 2015. Photo: Skiff Mountain Films

“Even before [I took part in] the classes, the existence of Bard College in that space allowed me to reimagine what I was capable of and to think of myself as a college student,” Tatro said.

My mother has a saying that she has repeated to me in trying times: If the train doesn’t stop at your station, it isn’t your train. It is meant to convey that not every job, or person, is meant for you. But what if you never know that your train exists? Our carceral state, one that prioritizes punishment over the actual correction that the facilities promise, is the America we continue to build. That’s why it is so urgent that Bard Prison Initiatives become the rule, not the exception.

“When Thomas Jefferson said, ‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,’ he wasn’t after material things in a marketplace of objects. He was after lifelong learning,” Burns said to me when we spoke. “I think what College Behind Bars suggests is the power of education.”

Neither Burns nor I have a stake, as this society of ours does, in the dehumanization of people end up incarcerated. The millions sunk into a failing prison system are more like an investment, maintaining a status quo that rots the very notion of a fair and just America but at least makes the elite feel like the heroes of their own story. Those who profit from every loophole that benefits the wealthy, white, and privileged may not want to see someone like Giovannie Hernandez coming out of prison after nearly 12 years with a degree and ready to make America more equitable.

The work BPI does is also a strike against recidivism. These people are less likely to go back to jail or prison. We know that there are elites who either enjoy looking down on folks or who actually benefit financially from people going to prison. Studies and experience have been proven that increasing opportunities for prison education reduces crime, helps communities thrive, and boosts the economy. Those of us without private prison stock should all want fewer people incarcerated and more education for those who are. Instead, we’ve seen states like Pennsylvania, Ohio, and West Virginia either seek (unsuccessfully, after protest) to block book donations from the public or charge those who are locked up egregious amounts to use e-readers.

But doesn’t it lift us all to see these folks come out of prison not just with more skills and more education, but with more hope? It is hardly a spoiler to tell you that a documentary like this ends with a graduation, and the overriding emotion that both the graduates and the audience are left with: hope. What you see at the end is a testament to the power of education, and why it remains such a dangerous and underrated weapon against a racially and economically unjust status quo in this nation.

When I spoke to Hernandez, he told me that he didn’t really have hope in prison before the Bard program entered his life. “I felt that I had to carry myself in a manner like I couldn’t care too much,” he said to me. “It was a defense mechanism. But Bard made me care about something. It gave me a way to figure it out.”

Now a Bard graduate and a case manager for the Brooklyn Community Bail Fund, Hernandez wrote an op-ed in USA TODAY in which he described his education as “emerging from Plato’s cave.” He told me that Novick, the director, found his story particularly moving.

“At the very beginning of the film, Giovannie talked about the person who encouraged him to apply to BPI,” Novick said. “The single kindest, most loving thing anyone had ever done for him was to force him to apply to the program. I think there’s just this sense of untapped potential that has been languishing, for lack of a better word, and neglected in our society — particularly in communities of color and other underserved communities where there’s generations of people who have ended up incarcerated and been exposed to subpar education.”

That is why the experience of watching College Behind Bars is, as Novick describes the process of making it, so inspiring and heartbreaking. She, an alumna of Yale, and I, who went to Penn, lamented that universities like those were sitting on multibillion-dollar endowments and didn’t have programs like Bard’s.

“These places,” Novick says of places like our Ivy League alma maters, “are just hoarding privilege and just sustaining and perpetuating inequality.” Novick noted that Yale did have a prison program this year that used a grant from BPI — ”because they didn’t want to put their own resources into it, if you can imagine” — that was very successful, proving that elite universities should be looking to prisons not merely to be charitable and to contribute to society, but to remain competitive. “If you, Fancy College, pride yourself on being the place where the most brilliant students develop their potential, you are missing out on an extraordinary talent pool.”

Bard Prison Initiative (BPI) graduates celebrate at Taconic Correctional Facility in June 2017. Photo: Skiff Mountain Films

And if these institutions can’t just do it for their own benefit, perhaps they’ll understand — as Bard College clearly has — that it is part of their mission to help everyone realize their own humanity. If anyone is watching, I hope that some of my fellow classmates and the administrators at universities like Penn are watching College Behind Bars. The people who hold the purse strings, the professors who love to signify their positivity online and in their published work, and those students and alumni looking to make a difference: This is your chance. If your college or university won’t use its endowment or solicit donations to establish such a program and share its prestige, find one that will. Every state, every locality, every prison should be educating those who are incarcerated. You see the blueprint. Follow it.