There is a mood of unease gripping the inmates. The unspoken fear is many of us will die alone in our cells without access to proper medical treatment.

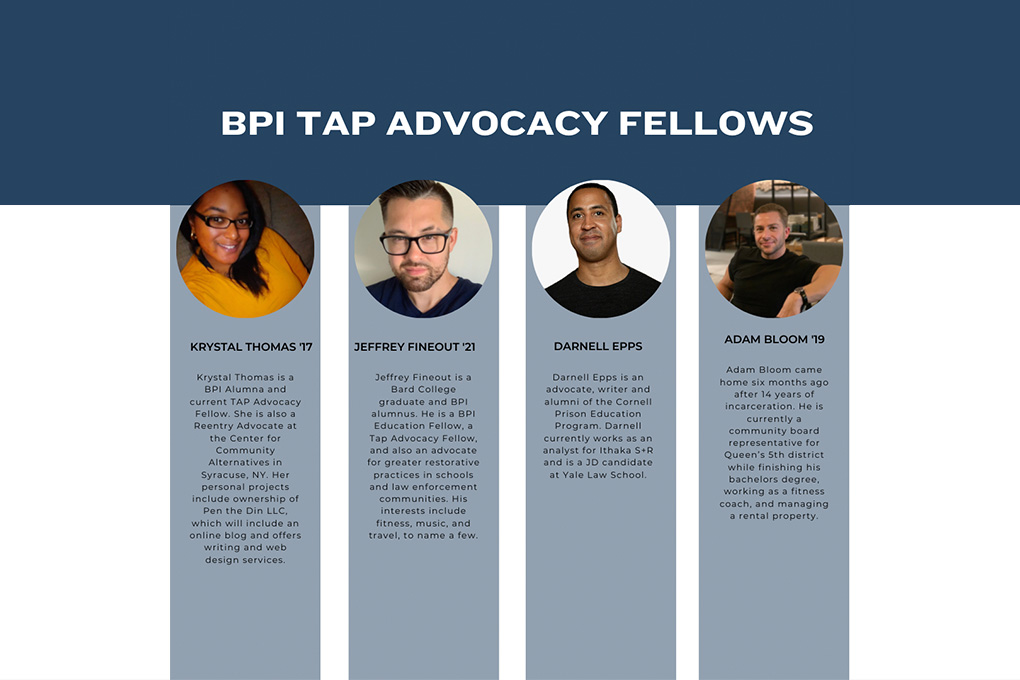

On Friday, 13 March, a site director from the Bard Prison Initiative told me and other inmates that professors wouldn’t be coming to teach classes for the foreseeable future. The director explained that this was a precautionary measure to avoid accidentally exposing students to Covid-19. This was the first sign that a lot of things around the prison were going to change. Given the extensive media coverage of the virus, I expected that Bard would tell professors to take such precautions. But I didn’t account for how dramatically Covid-19 would alter my life as an inmate.

Unfortunately, I didn’t have to wait long to find out. The very next day an announcement was made informing inmates that “out of concern for the safety and wellbeing of staff, all visits from the outside to inmates” – ie family and friends – would be “suspended until April 11, 2020, with the exception of legal visits”. In order to compensate for the visits being taken away, the prison would provide inmates with five free letters via postal mail, two free electronic email stamps via JPay, and one free phone call via Securus a week until the crisis resolved itself.

The mood within the prison immediately became grim. The realization of not being able to receive visits filled inmates with a sense of dread. All I kept thinking was: what if I never get to see my family again? Though I understand that shutting down the visits was the right decision to keep everyone safe, the thought of not being able to physically see my loved ones troubled me. But I, like every other inmate, had to quickly adapt to this new reality.

The following week, the prison took further measures to combat the virus. They shut down the gym, basketball court and inside showers. Inmates were now forced to congregate outside in the prison yard as a form of recreation. They also shut down the prison’s industry (where inmates work), the school building and every place of inmate worship. Next, civilian staff were restricted from entering the facility, leaving the guards and the inmates as the only people inside the prison, plus limited food and medical staff.

At this point there were no known reported cases of the virus within the facility, but Covid-19 had officially made its mark. Everyone believed we were in for a rough couple of weeks. Fortunately, that was not the case. In some ways, living conditions for inmates have oddly improved: inmates now have more access to showers and cleaning supplies, and for the first time in the almost two years that I have been here, conflict between staff and inmates has dropped significantly. It’s as if everyone knows that Covid-19 is the true enemy, and that we must somehow stick together to combat it or face collective defeat. At least that’s how it appears on the surface.

But there is a mood of unease and anxiety gripping the inmate population. Our main fear is that a staff member will contract Covid-19 on the outside, then bring the deadly virus into the prison. Inmates are walking on eggshells because everyone knows that there aren’t enough ICU beds or ventilators in the prison’s hospital to treat an influx of Covid-19 patients. The unspoken fear is that many inmates will die alone in their prison cells without access to proper medical treatment.

Is this a legitimate fear or simply a case of paranoia on the part of inmates? Many inmates believe the inconsistent precautionary measures taken by the prison to combat Covid-19 actually place everyone at greater risk of contracting the virus. For instance, the facility now operates on a modified schedule to discourage large gatherings of people, yet when inmates and staff walk through the corridors or frequent the recreation yard, they are not mandated to practice physical distancing. Despite the daily warning given over the loudspeaker advising everyone to stay six feet apart, the practice is not enforced; the concept of physical distancing within the facility is a farce masked by the pretense of keeping everyone safe.

Under the current (in reality quite relaxed) physical distancing practices, a person with asymptomatic Covid-19 would be able to infect the entire prison population within a matter of hours. Inmates and staff are almost always coming in close contact with each other, so it is highly unlikely for one not to infect the other and vice versa. Even when inmates are locked in their cells, there is no guarantee they won’t come in contact with staff, since prison officers must do rounds and constantly check on inmates. The best one can hope for is that no one – either staff or inmates – contracts Covid-19.

We have been lucky so far, given the dire circumstances that the people of New York, and everyone affected by the virus across the globe, currently face. So far the authorities have issued no information on when the prison will return to normal operation. But I imagine it will be far beyond the 11 April date given to us in early March. In the meantime we wait, and hope for the best.

Kenneth Hogan is an inmate at Eastern New York correctional facility

This article was published on Friday April 10th in The Guardian US Edition