U.S. college programs for incarcerated students were largely defunded in the 1990s. At the time, it was seemingly great news for “tough on crime” advocates, but in 2014, a new debate erupted out of New York state. Last February, Governor Andrew Cuomo proposed an initiative to both educate New York’s prison population and save taxpayers money. It costs $60,000 per year to house an inmate in prison, and it costs an estimated $5,000 per year to provide higher education. “Right now, chances are almost half, that once he’s released, he’s going to come right back,” explained Cuomo. With the country’s high rates of recidivism, solutions that reduce that rate are the best method for reducing overall costs.

Ensuring that former inmates are educated and have the skills to give back to their communities may seem like a no-brainer, but these programs face extraordinary resistance. The common argument against prison education is that while law-abiding college students are struggling, taxpayers don’t see the fairness in paying to educate criminals. However, prison experts argue that public-funded prison education programs actually stand to help tax-paying citizens save money. Gerald Gaes, who served as an expert on college programs for the Federal Bureau of Prisons in the 1990s, says the key is reducing the number of inmates who break the law and wind up back in expensive prison cells.

A 2013 joint study by the RAND Corporation and the Department of Justice found that prisoners who participated in education programs, such as GED education, college courses, and other types of training, were 43% less likely to return to prison after their release. The report, entitled “Evaluating the Effectiveness of Correctional Education,” was the largest-ever analysis of correctional educational studies, and the findings indicate that prison education programs are cost effective. According to the research, a $1 investment in prison education reduces incarceration costs by $4 to $5 during the first three years after an inmate’s release.

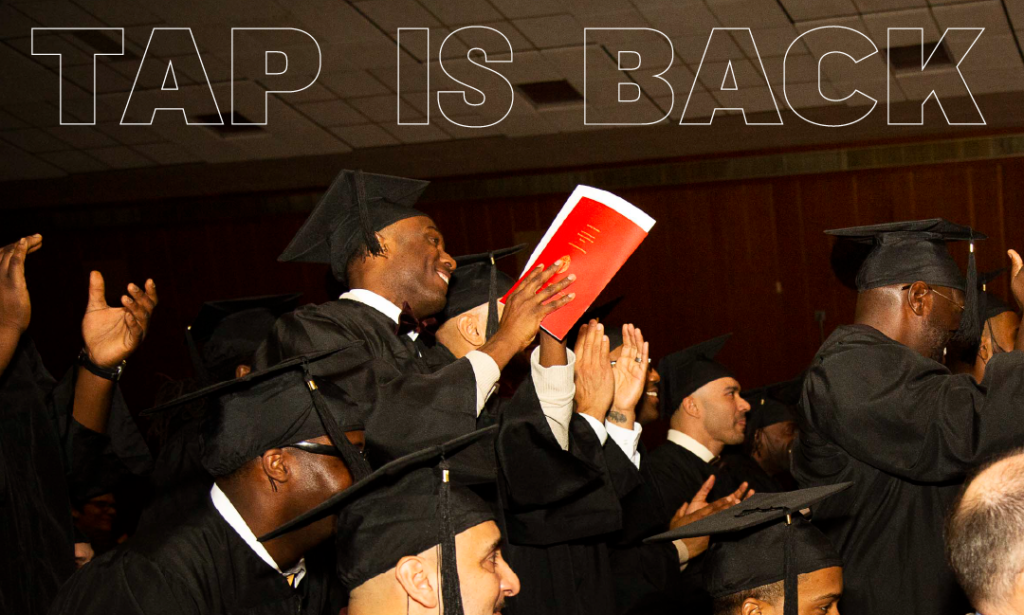

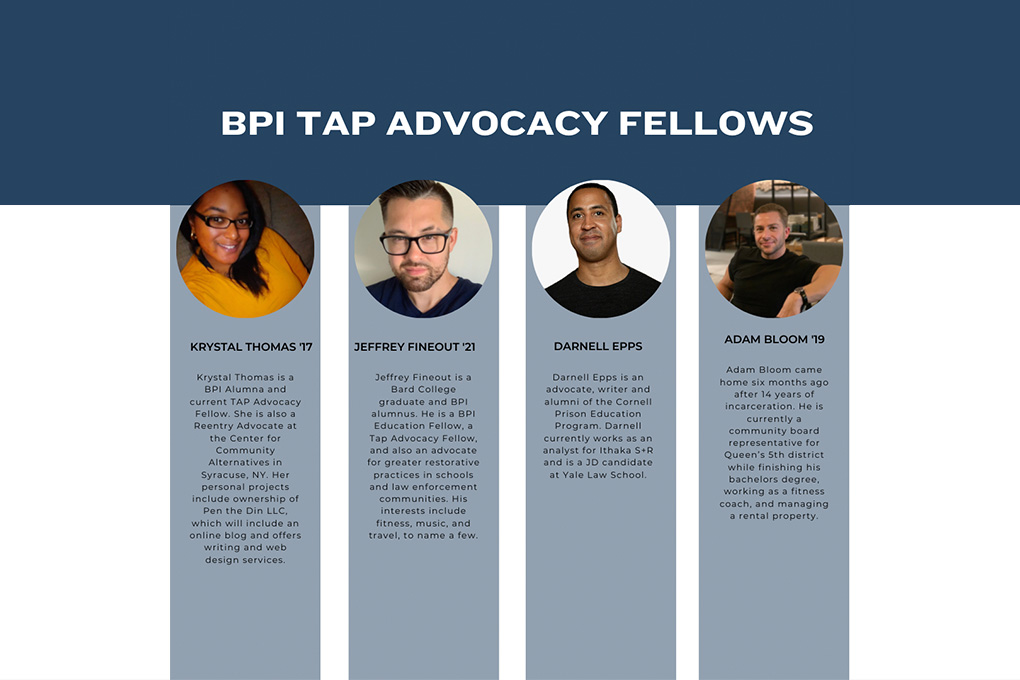

College programs in prisons are already demonstrating the strong impact of education on recidivism rates. Nationwide, the three-year rate of recidivism is nearly 50%. The Hudson Link for Higher Education in Prison has spent 15 years facilitating college programs for New York inmates. Of the 168 graduates of this program who were released from prison, the three-year recidivism rate is less than 1%. At the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI) program in upstate New York, just 2.5% of students who completed a degree returned to prison.