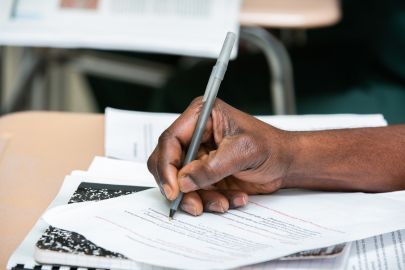

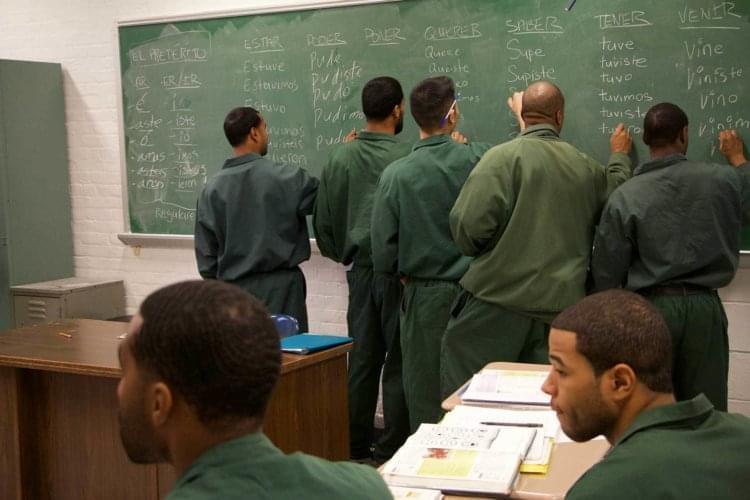

Bard Prison Initiative (BPI) students conjugate Spanish verbs at Eastern New York Correctional Facility. (Skiff Mountain Films)

The new four-part PBS documentary “College Behind Bars” examines what higher education looks like in New York State prisons — and the impact it has on incarcerated students. Lynn Novick produced and directed the film, and Ken Burns is an executive producer. Illinois Public Media and Illinois Newsroom have reported extensively on prison education in Illinois.

The PBS documentary follows incarcerated men and women enrolled in the Bard Prison Initiative, or BPI. The film airs on PBS stations and streams online on Nov. 25 and Nov. 26.

Illinois Public Media interviewed the senior producer of “College Behind Bars,” Sarah Botstein, and a graduate of the BPI program, Wes Caines — who also served as an adviser to the documentary production team.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Sarah, we get to know the BPI students as students before we learn anything about the reason why they’re in prison. Was that an intentional decision on the part of the producers?

Sarah Botstein: Before we turned any of our cameras on, we wanted to tell a story that was first and foremost about education. We wanted to give our viewers a chance to get to know the students in the classrooms that they were following. And we found that every other film we watched, and all the other articles and books written, often identified the subjects with their criminal records very, very early — if not on the lower third identifier. And we philosophically wanted to do something different, and have the subjects and the students tell their stories in their own words over the course of getting to know them and their families.

Wes Caines: I spend a lot of time criticizing (the New York) state prison system, but I think that I also could acknowledge that it was enormously courageous of them to allow this project to happen. Prisons are the notoriously dark spaces, where the introduction of light is frowned upon. It’s particularly dogmatic around this sense that what we have to deal with on a day to day, at least from the point of the administrators, is stuff that people in the quote unquote real world wouldn’t understand. And so there’s this like hyper effort made to really keep segregated and contained everything that happens behind the walls of a prison. They didn’t control the direction of this film. They didn’t control the messaging or the possible takeaways from this film. But to have opened the space for it to happen was truly remarkable.

One thing that this film does quite effectively, I think, is contrast the reality of prison, the inhumanity of prison, how challenging an environment that is to exist in and the oasis that having access to an education really provided for people In the BPI program. Wes, I’m wondering, was it difficult for you to navigate that reality of being in prison and also being a student in a rigorous college program?

WC: Absolutely. It was challenging. One of the things that I did personally is I didn’t allow for the challenge of navigating both a college program and a prison sentence to be a place for me to get stagnant. So I think what’s unique about being in a prison is that you don’t have the freedom of choice that you would have if you’re at liberty. So there is a challenge to it. In the film, there’s this talk of double consciousness and the voice. There is that double consciousness at play being both a prisoner and a college student. The challenge is to always be prepared when you step into a classroom, and the door closes behind you, is your willingness understand that you are there now to engage the text, and engage your colleagues, and engage the process of learning in a way that literally places to the side the fact that you also have to simultaneously live in a cage.

One of the driving questions of this documentary is what happens when we provide an education that’s typically only afforded to the lucky, the entitled and the rich to others. Sarah, I’m wondering if, after doing this years long project, you walked away with an answer to that?

SB: My answer to that question is that I believe, even more than I did in 2014, that education is a right and not a privilege. That the overwhelming burden of the cost of higher education and the terrible state of our public school system is something that we have a responsibility as a society to address and try and fix, and that education is central to the human experience. And inspiring young people is as important as inspiring older people. And I think one of the other points the film makes that isn’t as explicit but you take away from it, is that learning does not just happen with the young. Your foundational education doesn’t have to be X, Y or Z to write a bachelor’s thesis in applied mathematics or history. You can continue to learn in the classroom as an adult as you do as a young person. I feel that the experiment BPI has attempted to try is proven in the film.

Wes, I want to ask you that question, but frame it this way: what did your experience and BPI do for you?

WC: Wow. It did everything. I don’t sit in the office of The Bronx Defenders, a public defender office in New York City, as the chief of staff but for this opportunity. It literally set me up for success post-prison. And I’m not a sample of one, as your listeners will see when this film comes out. The men and women who were followed over the course of these few years in this film, who have been released, we are all engaged in ways in our communities and in business that are not typically thought of as post-incarceration. It just doesn’t happen without BPI and Bard college making this investment and this commitment to people who society wrote off as, you know, not being worthy of an education. But then not being worthy of the investment that it would take to really see us to reenter and to reintegrate in any meaningful way. And I think there are various ways, but one of the ways that this could happen is by a quality education.

Wes, you lived and breathed this program you advised in the making of this film. I’m wondering what do you hope viewers in Illinois, but also viewers across the country learn from this documentary,

WC: I would hope that viewers take away the humanity that we lock away. And this humanity has the ability to be redeemed, and one of the pathways for that redemption is being educated. I would also hope that they would take away a broader notion about just education generally, both within prisons and in communities. What would have happened, you know, to the men and women across this country, if our public education system really valued them in a way that challenged them in a way that provided pathways to success — that did not direct them to incarceration. We have the defunded public education in this country to a degree that has not served us very well. And I’m hoping that we start to reexamine that.

To learn more about “College Behind Bars,” visit PBS.org.