John Yang ’23 began his studies with the Emerson Prison initiative, and now is a junior on the Boston campus. From the very first class he took as an Emerson student, John Yang ’23 said he learned a new way to look at the world and describe how it functions.

It was called Power and Privilege, taught by Associate Professor Mneesha Gellman, and it was the first course offered to students enrolled in the Emerson Prison Initiative (EPI), which Gellman also directs.

“It opened my eyes to a language that I didn’t know, especially at such a high academic level of understanding what power dynamics meant and how they create the structure that you, as a human being, have to live in and function in,” Yang said.

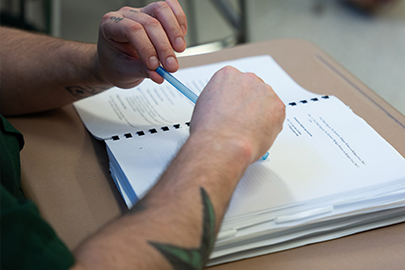

Yang was one of the first cohort of EPI students enrolled back in 2017. EPI offers a pathway to a college education to admitted students incarcerated at Massachusetts Correctional Institution at Concord (MCI)–Concord, a medium-security men’s prison about 20 miles west of Boston. Students are taught by Emerson faculty, and are held to the same academic standards as their counterparts on the College’s campus in Boston – despite not having access to resources: internet, equipment, libraries.

From day one, students were able to earn college credit for the courses, but a little over a year after launching, Gellman, with the support of the College administration and then-President Lee Pelton, was able to expand EPI into to a degree-granting course of study.

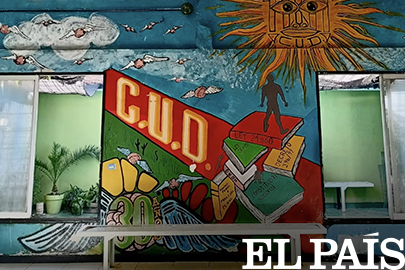

On Tuesday, September 27, five years after launch, 10 EPI students officially became graduates of Emerson College with bachelor’s degrees in Media, Literature, and Culture, a major designed for EPI within the Marlboro Institute of Liberal Arts and Interdisciplinary Studies. Six of the students participated in a ceremony at MCI-Concord attended by family, friends, and faculty. Pelton, now President and CEO of The Boston Foundation, was the commencement speaker.

“This day exists because at some point, each of you said ‘yes,’” Gellman told the graduates and guests last month. “Yes, we can do a pilot program … yes, we can drop off boxes of books and make photocopies, yes, we’ll teach, and most of all, yes, we will learn! We will come back day after day, semester after semester, with a hunger for knowledge so fierce that it will inspire us to be the best we can possibly be.”

Yang wasn’t at last month’s commencement ceremony; he was released in 2021. But he’s determined to continue his studies and finish his degree. He enrolled in courses on Emerson’s main campus beginning last fall, and is currently a junior at Emerson, one of two EPI students so far to make the transition from EPI in Concord to Emerson in Boston.

Teaching in Prison

In another EPI milestone last month, Brandeis University Press released Education Behind the Wall: Why and How We Teach College in Prison, a book edited by Gellman that lays out the benefits, challenges, and opportunities in teaching college in prison. It includes essays written by educators who have taught in college-in-prison programs, including many EPI faculty. A celebration of the book’s launch will be held Thursday, October 6, 4:00-5:30 pm, in the Bordy Theater.

Wendy Walters is one of the contributors to the book. The Writing, Literature and Publishing professor teaches a class to EPI students on Afrofuturism, and another called Rewriting the Maps: The Politics of Location.

Walters said she had always wanted to teach in a college-in-prison program, and was excited when EPI was created. Teaching in a prison gets to the core of what drives most educators to do what they do, she said.

Left to right, EPI Director Mneesha Gellman, EPI Interim Director Cara Moyer-Duncan, and EPI Interim Assistant Director Stephen Shane at last month’s ceremony honoring EPI graduates. Photo/Joshua Wachs ’87

When EPI students come into a classroom, they’re fully focused on the discussion and each other, Walters said. The students’ commitment to one another was “very, very moving.”

“You’re really not just engaging in an individualist education process, nor is it limited to the cohort of … graduates that were there. That spreads within the population in the prison,” she said. “They’re really modeling the transformative power of education.”

Gellman said during the September 27 ceremony, one of the graduating students spoke about how the culture of learning and discourse has filtered throughout the prison, even to those who weren’t enrolled in EPI.

Before Emerson started offering classes at MCI-Concord, men in the yard might argue about music or something that happened within the prison, the graduate said. Now, as they’re walking around, they argue about Foucault.

Moving Forward

EPI admitted its second cohort in summer 2021, and introduced a new minor in Economics, in part a response to the interests of the students themselves, said Interim EPI Director Cara Moyer-Duncan, who is leading the initiative while Gellman is on research leave. Many have expressed an interest in business classes, and Moyer-Duncan said an Economics minor would accomplish many of their goals and still work within the constraints of the prison system.

Over the summer, EPI teamed up with Tufts University and Boston College to begin offering courses at Northeastern Correctional Center, a minimum-security men’s prison across the street from MCI-Concord. Oftentimes, men incarcerated in a medium-security facility will step down a security level before being released. EPI students, as well as students in college programs at other facilities offered through Tufts and BC can request to be transferred to Northeastern and take classes pooled together so they don’t lose class time before release, Moyer-Duncan said.

EPI also created the Reentry & College Outside Program (RECOUP), a program that connects recently released students with support programs that help the students acclimate and navigate the world outside prison walls, with the goal of allowing them to continue their studies.

Moyer-Duncan said in the past six years, she has seen shifts in the way college in prison is understood in society, including at the federal level with the introduction of Second Chance Pell grants to incarcerated students.

“I think there have been shifts. For EPI, it’s been important to promote an understanding of the transformative possibilities of access to education in prison, and why this is something worthy and important for communities to embrace,” she said.

John Yang ’23 would like one day to direct a program that helps formerly incarcerated people transition to their communities. Screen shot from EPI video

Real Impact

EPI student Ahmad Bright ’25 can attest to the program’s value

Bright said the opportunity to be in a classroom and earn college credits was an easy sell for him when he was in Concord. Now a sophomore at the Boston campus, he is supplementing his 16-credit course load with a four-night-per-week coding boot camp for formerly incarcerated people run through Columbia University. He’s considering changing his major to another interdisciplinary program having to do with global development, though he’s leaving his options open.

“[EPI] just literally created a lifeline for so many people inside of prison who knew they wanted more for themselves, but maybe just didn’t have the platform to get more for themselves,” Bright said. “It helped kind of build a community for us [who] were inside, but at the same time, it’s [been] a lifeline to the outside, because through EPI, we’ve made so many contacts with our professors, our [teaching assistants], and it’s just been an incredible experience.”

Yang said as a junior, he’s sticking with his original Media, Literature, and Culture major, but he’s adding in a minor in Nonprofit Communication. That’s because he hopes to one day run a college-in-prison program himself, or run a program that helps post-incarcerated people learn the skills that will help them transition into the community.

“Some of the issues I’ve been pushing for is mental health awareness for the post-incarcerated community, because the majority of us, we’re coming home after decades, if not double decades, of incarceration,” Yang said. “How do you expect somebody to have the competency level to go back to work and deal with a boss, deal with kids, deal with … social anxiety, [develop] financial responsibilities, and stuff like that?”

Why We Do It

Gellman said in the book, she makes the case that the idea of college in prison should receive bipartisan support, if only because it makes good fiscal sense.

Incarceration is extremely expensive. The Massachusetts Department of Corrections spent $732 million to incarcerate just over 5,000 people last fiscal year, Gellman said. Research shows that access to college in prison reduces recidivism – one study found that every associate’s degree earned in college saves the state $130,000.

But college in prison isn’t just about saving money, Gellman said, it’s about building a better society.

“Yes, it decreases recidivism, yes, it makes fiscal sense, yes, it is a social justice intervention,” Gellman said. “Also, it’s a space where human beings who are incarcerated have the autonomy to explore the life of the mind on their terms. And that brings with it a sense of agency around education that is really fundamental to a human rights framework we want, not just in prison, but in the world.”