A college education transformed [formerly incarcerated people’s] lives. But some critics fear low-quality programs will rush in.

PHOTO BY LEE WEXLER

Vivian Nixon, foreground, greeting Turquoise Martin, a 2019 college graduate who was once incarcerated. Nixon, executive director of College & Community Fellowship, is [formerly incarcerated] herself.

It was during the three years she was confined to a medium-security prison in upstate New York, tutoring peers who could barely read, that she started a decades-long fight to expand educational opportunities for people serving time. Nixon, who went on to earn a bachelor’s and a master’s degree, the latter in fine arts from Columbia University, became an ordained associate minister and leads a nonprofit that helps eliminate barriers to college. She would prefer to be known for those accomplishments.

Still, in statehouse testimony and campus lectures, she travels back through the barbed-wire gates of the State Correctional Institution at Albion to describe the effects of incarceration and educational deprivation on its disproportionately Black, largely impoverished occupants.

“I’m willing to relive the worst period of my life until people get it,” said Nixon, who was released in 2001 and worked her way from community organizer to executive director of College & Community Fellowship. The nonprofit, which supported her as she earned degrees from the State University of New York Empire State College and Columbia, provides college counseling, tutoring, support networks, and career guidance to formerly incarcerated women.

In December, Nixon thanked other prison activists whose stories helped persuade Congress to lift a 26-year ban on federal Pell Grants for prisoners. That move, part of a year-end Covid relief and omnibus package, could make nearly half a million inmates in federal and state prisons eligible for the need-based grants. The Pell victory, she said, made the painful retelling of their stories worthwhile.

“Every time we sat before elected officials, sharing expertise and stories about the transformative power of education, we lived a paradox,” Nixon wrote in a statement after the ban was lifted. “The power of our testimony came with the stigma of incarceration. Yet, chins held high, we claimed that we are worthy of educational opportunity. And many educators stood with us — keeping hope alive by providing college behind bars when Pell was not an option.”

The addition of thousands of potential new recruits for enrollment-starved colleges is likely to result in an expansion of options for prison programs, ranging from short-term work-force certificates to associate and bachelor’s degrees.

A survey conducted by The Chronicle with support from the Ascendium Education Group found that 84 percent of the 763 college faculty members and administrators who responded strongly agreed that incarcerated people should have access to higher education, while another 15 percent somewhat agreed. (The Chronicle will publish a report later this month analyzing the results of the survey, as well as the landscape for higher education in prison.)

Expanding such opportunities has enjoyed growing bipartisan support as a way to reduce recidivism, save taxpayers money, and mitigate the discriminatory effects of mass incarceration and unequal schooling. But some fear that inmates might end up exhausting Pell eligibility on poor-quality programs that are rolled out too quickly, without the wraparound supports and face-to-face contact they say incarcerated students especially need.

Many educators stood with us — keeping hope alive by providing college behind bars when Pell was not an option.

When the Covid-19 pandemic hit last winter and colleges scrambled to move online, prison-education programs were at a disadvantage, since inmates typically aren’t allowed on the internet and have limited access to technology. Now, as technology restrictions have eased in some prisons, and programs have experimented with offline content-management systems, some advocates for prisoners fear correctional institutions will gravitate toward online programs that deprive inmates of personal contact with professors and classmates.

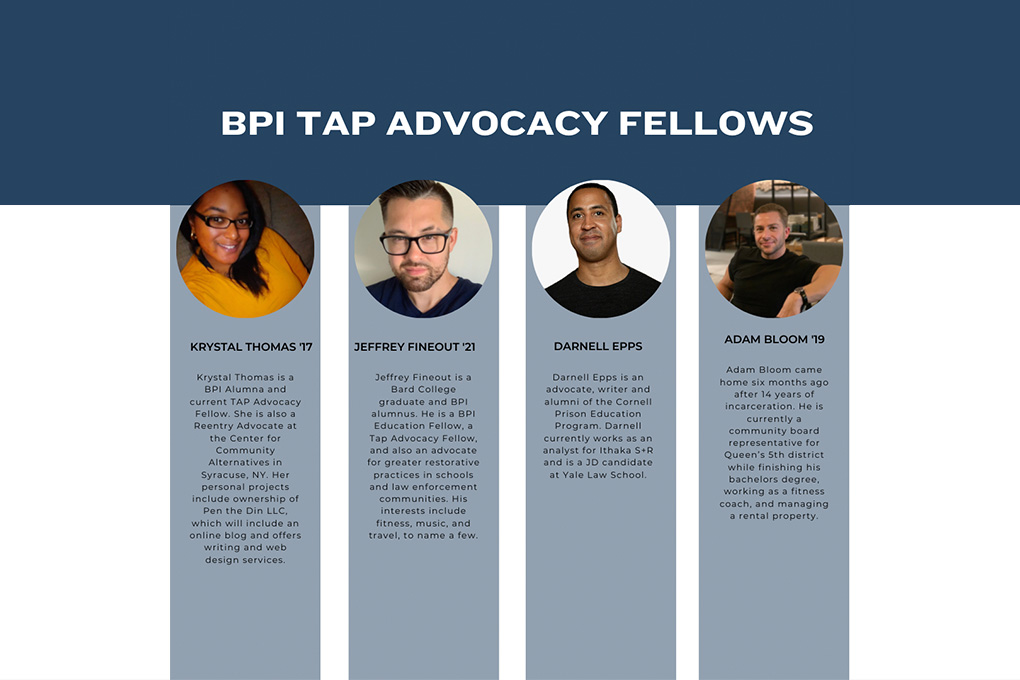

“We can’t forget about the importance, both for education, and for mental well-being, of the human connection that’s forged in the classroom,” said Kurtis Tanaka, a qualitative analyst with Ithaka S+R who studies higher ed and technology in prisons. Technology has the potential to deliver education efficiently, he said, but it shouldn’t supplant the in-person instruction that is often more effective.

Rebecca Ginsburg, director of the Education Justice Project, a college-in-prison program of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, agrees. “Many of us continue to be concerned that when Covid lifts, we’ll be told ‘that went really well. No need for you to come back,’” she said.

The fight to restore Pell Grants for prisoners goes back more than two decades. Until 1994, incarcerated people could apply for the grants to help cover the cost of college courses. But during President Clinton’s administration, a tough crime bill, championed by then-U.S. Sen. Joseph R. Biden Jr., stripped them of that eligibility. Supporters of the ban argued it was unfair to expect taxpayers to foot the bill for convicted felons to attend college when law-abiding citizens were accumulating college debt.

In the coming years, as prison populations exploded and recidivism rose, the number of students taking college courses plummeted.

The Second Chance Pell program was started in 2015 under the Obama administration and expanded by the Trump administration last year to 130 colleges in 42 states plus the District of Columbia. Biden, now president-elect, has said his support for the Pell ban was a mistake.

Since 2016, thousands of inmates have taken advantage of Second Chance Pell to pursue college credentials that could help them land better paying jobs, support their families, and make positive contributions to society when they’re released. With the ban on Pell Grants lifted, that number could swell to about 463,000, according to the Vera Institute of Justice. The legislation, signed on December 27, also removes a barrier to Pell Grants for people with drug-related convictions.

Prison education has been widely welcomed as a way to turn lives around while reducing crime and saving taxpayers money. A 2018 study published in the Journal of Experimental Criminology found that inmates who participated in higher-education programs while incarcerated were 48 percent less likely to return to prison. For every dollar spent on higher education, taxpayers save $4 to $5 because of lower recidivism, increased employment, and stability for formerly incarcerated people and their families, analysts found.

But the benefits of higher education extend far beyond keeping students away from crime, advocates argue. College education has ripple effects on families, as parents provide role models for their children. Providing productive outlets and leadership opportunities for incarcerated people also makes prisons safer and saner places. Perhaps most importantly, it gives people hope for the future and the tools they need to reintegrate into society.

Some prisoners’ advocates caution, though, that there’s a potential downside of making Pell Grants more widely available. “There is a good chance that the online, for-profit education industry and other independent actors, with a cheap, low-quality business model, are likely to develop the relationship and strategies to take over the field,” said Jody Lewen, president of Mount Tamalpais College, formerly known as the Prison University Project at San Quentin State Prison.

“They will say ‘we can do this without even burdening you with teachers, we’ll just do this online,’” Lewen added. Her program has just over 300 students from San Quentin Prison enrolled, and it relies on volunteer adjuncts from Bay-area colleges, including Stanford University, the University of California at Berkeley, and San Francisco State University. It offers a general-education associate of arts degree.

Lewen said she also worries about financially struggling public colleges, including community colleges, looking to prisons to fill their seats. “There are colleges that are more desperate than ever for revenue, and now all of these additional students are eligible for Pell,” she said. “It’s the perfect storm for substandard programs and exploitation.”

Colleges that offer a smattering of unrelated courses without access to remedial help can mislead students into thinking they’re well on their way to a bachelor’s degree, she said. “Students come in with so many units and they say they’re so close to completion,” but they can’t write a coherent paragraph, she said.

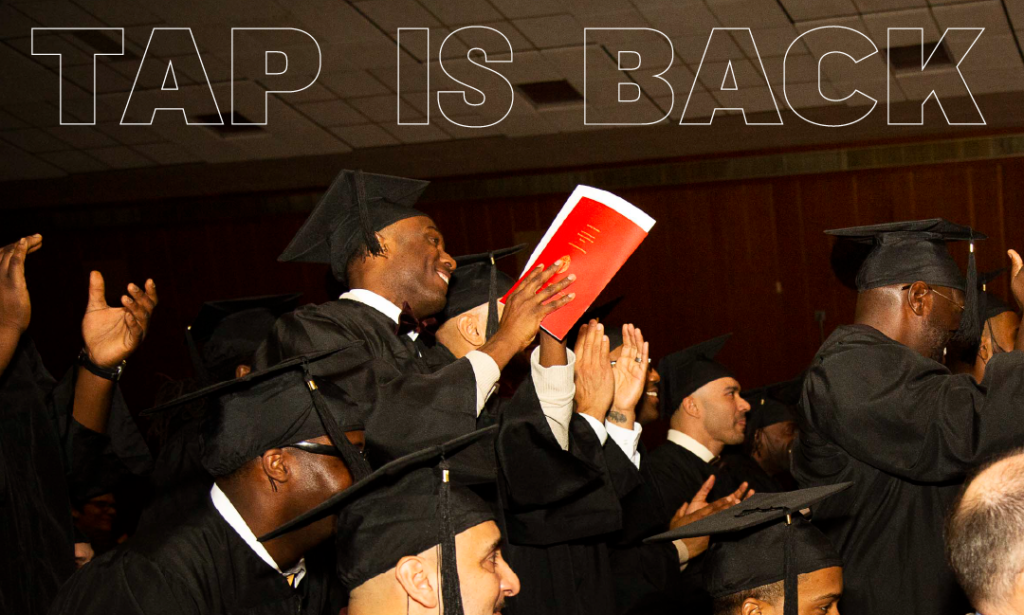

Quality will be crucial as new programs roll out, said Max Kenner, founder and executive director of the Bard Prison Initiative. “This isn’t a space for colleges to be profiteering in,” he said. “It is a space where they can engage students and communities they have historically neglected.”

“This isn’t a space for colleges to be profiteering in, it is a space where they can engage students and communities they have historically neglected.”

Boosting enrollment isn’t the only reason more colleges are likely to take a second look at prison education. Colleges are facing increasing pressure to take concrete actions to address the inequities in educational opportunities that have been exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic.

African Americans make up 13 percent of the nation’s population but more than a third of the country’s prison population, according to the U.S. Department of Justice. Meanwhile, only 6 percent of inmates held postsecondary degrees in 2012 and 2014, compared with 37 percent of nonincarcerated people, according to a 2019 report by Ithaka S+R.

Among those celebrating the restoration of Pell Grants was Elon Molina, 43, who earned associate and bachelor’s degrees from the Bard Prison Initiative while serving 15 years for armed robbery. BPI, an offshoot of Bard College and one of the nation’s most rigorous prison-education programs, enrolls more than 300 students in associate and bachelor’s degree programs in six prisons across New York State. Molina was released from prison in March and is now working as a counselor in a nonsecure detention center for teenage boys who have had brushes with the law.

As a young man, he was in and out of prison, but he said the growth and reflection his liberal-arts education provided while he was incarcerated gave him the tools to be a productive citizen. This time, when he was released, “I wasn’t afraid to look someone in the eye and say no to something,” Molina said. “I had found my voice as a man.”

Click here to read the complete article.