Ellen Condliffe Lagemann is the author of Liberating Minds: The Case for College in Prison (The New Press, 2016), from which this article contains excerpts. She was formerly the Levy Institute Research Professor at Bard College and a Distinguished Fellow at the Bard Prison Initiative. She is now a Distinguished Scholar at New York University. The full essay, reproduced below, first appeared in the Education Against All Odds series on David Byrne’s reasonstobecheerful.world and can be found here.

Reversing the Tide

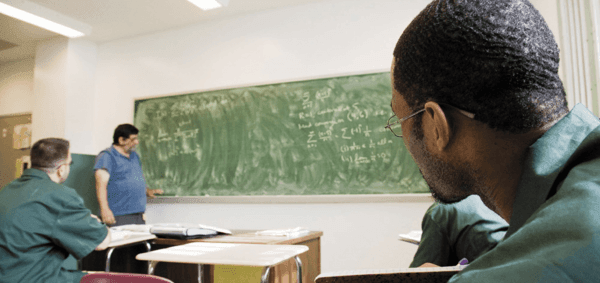

Students of the Bard Prison Initiative attending a calculus class

College degree programs like the Bard Prison Initiative give jailed students a chance to thrive once they’re released—and drive down the costs of incarceration for us all.

On a hot day in June 2008, I sat with about one hundred other visitors in the yard of the Woodbourne Correctional Facility in upstate New York. We had come for the graduation of the first cohort of students from the Bard Prison Initiative to receive bachelor’s degrees.

“All I knew before this was the street,” the first speaker remarked. “I was tied to its rules and expectations. Now I have read Plato and Shakespeare, studied history and anthropology, passed calculus, and learned to speak Chinese. I know the world will be what I make of it. I can make my family proud.”

They all spoke of their determination to contribute to society. “With this education,” another speaker announced, “I not only understand my debt to society, but I am also now in a position to repay it.”

These students were graduates of Bard College, which has awarded 450 degrees in New York State prisons over the last decade through the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI). Approximately 70 men and women who have been BPI students return home every year, many continuing their education and almost all—85 percent—securing jobs within two months of their release.

The graduates of the Bard Prison Initiative have all been convicted of serious felonies. Few finished high school before being sent to prison.

Typically atypical

In their lack of prior schooling, these men were entirely typical of the U.S. prison population. The roughly 2.2 million men and women now languishing in American prisons are among the least educated people in the country. Most have not gone beyond the 10th grade. But the Bard graduates are not typical in their post-prison lives. While the national rate of return to prison is over 50 percent, the rate for graduates of the Bard Prison Initiative is only slightly more than two percent. That means that 98 out of 100 BPI graduates leave prison and never come back. Even for those who have taken some classes but did not complete a degree the return rate is only five percent—still 10 times lower than average.

Bard Prison Initiative graduation day at Woodbourne Correctional Facility.

Recidivism rates for prisoners who have graduated from other college-in-prison programs are comparably impressive. Hudson Link, which offers associate’s and bachelor’s degrees through several different colleges at five correctional facilities in New York State, reports a return rate of two percent. The Cornell University Prison Education Program reports a seven percent recidivism rate for students who have completed fewer than three courses upon release, and zero percent recidivism for those who have gone on from Cornell to complete an associate’s degree. The Prison University Project at San Quentin State Prison, north of San Francisco, reports recidivism rates for its students of 17 percent after three years as opposed to a state rate of 65 percent.

Most alums of these programs move on to good jobs, many in social services and in public health organizations, although graduates have also found jobs in publishing, real estate and legal services. Many Bard alums have pursued graduate degrees, including New York University’s master’s program in urban planning, Columbia University’s master’s programs in public health and social work, and Yale University’s master’s program in divinity.

More evidence

Bard’s prison program was started by Max Kenner, when he was an undergraduate at Bard. Beginning with one workshop in one prison, BPI has spread to six New York state prisons and now offers both associate’s and bachelor’s degrees. It also anchors a consortium of similar programs at other colleges and universities across the U.S., including Wesleyan in Connecticut, the University of Notre Dame in Illinois and Washington University in St. Louis.

Until 2015, students enrolled in college in prison were ineligible for Pell Grants or other kinds of financial assistance, but this has been changing in recent years, making it likely that more colleges will open campuses behind bars.

As that happens, more formerly incarcerated men and women will be able to find employment. This will help them contribute to the support of their families upon their release from prison, thereby serving to interrupt the intergenerational cycles of imprisonment that accompany mass incarceration. With strong evidence that college programs reduce violence in prisons, the further spread of college offerings is also likely to improve life inside. It is for this reason so many prison superintendents favor college programs. The improved atmosphere college programs help to create benefits both people in custody and correctional officers.

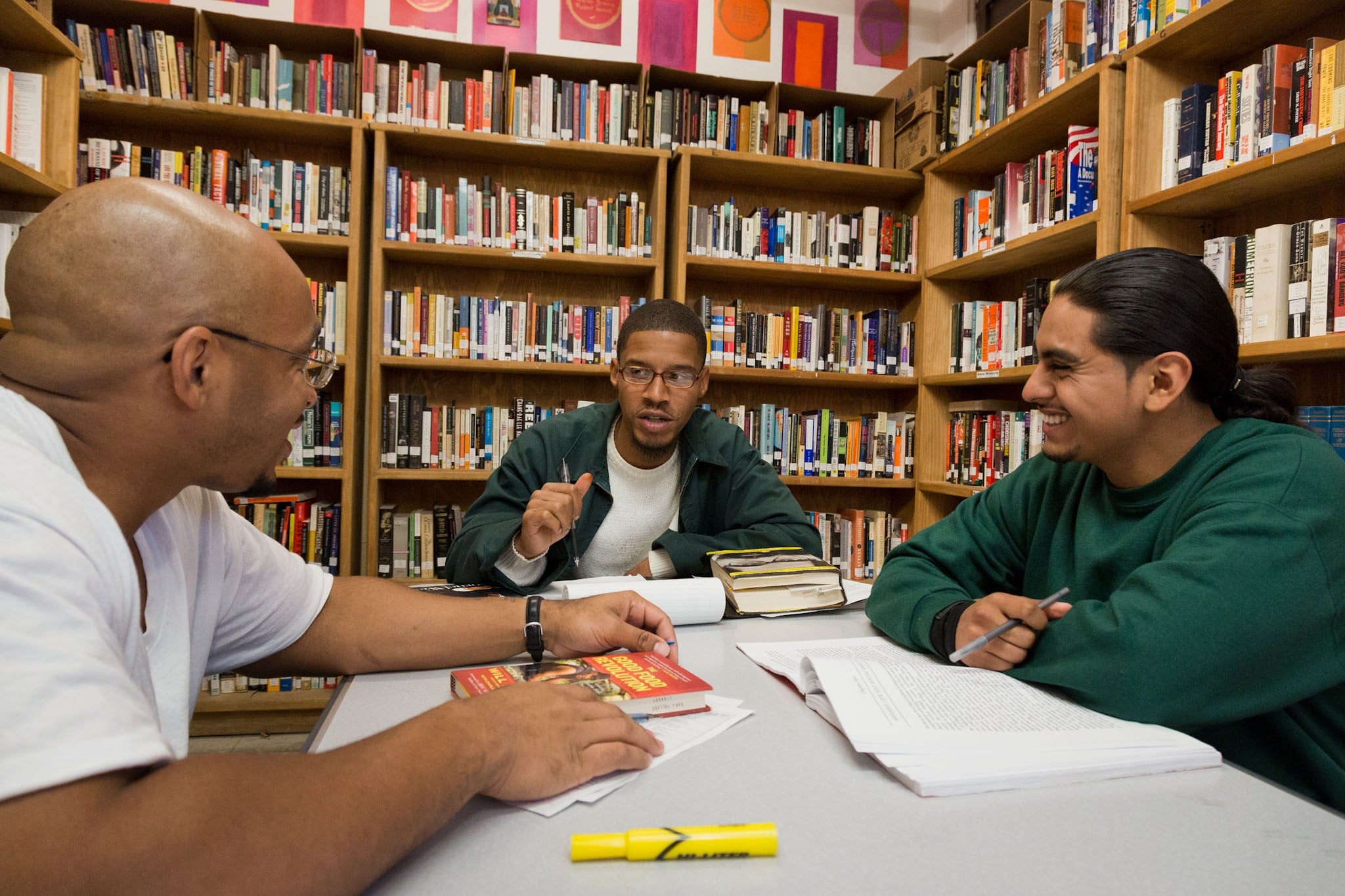

Bard Prison Initiative students

On average, between 2009 and 2015, American taxpayers spent nearly $70 billion a year on prison, and due to a dramatic increase in the size of the prison population and consequent boom in the building of prisons, the costs have been escalating. According to the National Association of State Budget Officers, between 1986 and 2012, overall state spending for corrections increased by 427 percent, from $9.9 billion to $52.4 billion.

Reversing the tide, so that less is spent on prisons and more on education, is critical for the nation’s economic future. Research indicates that cutting recidivism rates in state prisons by even 10 percent could save all 50 states a combined $635 million from their expenses on corrections—and that does not include the potential saving from reducing recidivism in the extensive federally run prison system.

In addition, college in prison can reduce crime. Estimates suggest that spending $1 million on correctional education, which includes basic adult education, GED instruction and vocational education, as well as more traditional college programs, would prevent 600 crimes from being committed, while spending the same amount on incarceration alone would prevent only 350 crimes.

The intangible outcomes

What little writing there is about college programs for people in prison tends to focus on these most easily measured outcomes, primarily rates of return to prison and the employment of students after their release.

But there is no study of which I am aware that addresses such important, if intangible, outcomes as gaining confidence and hope for one’s future, feeling excited about making significant contributions to the enrichment of other people’s lives, kindling a love of reading or an interest in keeping up with current events, or, most important of all, acquiring the desire and determination to continue learning. The stories of Bard graduates are important in communicating the full impact of college in prison.

One of those graduates is Erica Mateo. Her father died less than a year after she was born, and two years later her mother was disabled in a car crash. Though her grandmother stepped in to help raise Erica, she died when Erica was 11, and Erica was placed in a group home. Soon she was in trouble with her law. In 2002, she was sent to prison for assault. Now she is working for the Center for Court Innovation, developing programs to keep young people in the crime-ridden neighborhood of Brownsville, Brooklyn, from falling into the traps she did. I write about her story, and others like hers, in my book Liberating Minds: The Case for College in Prison.

Access for all

Throughout this nation’s history, more and more Americans have had access to education, and this has been especially evident in higher education.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, college was generally restricted to white men preparing to be ministers, lawyers, or doctors. During the Civil War, passage of the Morrill Land Grant Act established agricultural and mechanical colleges throughout the United States, broadening the purpose of higher education as well as enrollment.

Colleges for women and for African Americans opened soon thereafter, as did the great research universities. The great innovation during the twentieth century was the community college, which made access to at least two years of higher education virtually universal.

Including college in prison in plans for “college for all” will not only create benefits for the country as a whole, but it will also be in keeping with the tradition of expanding education opportunity that has played such an important role in fostering the development of this country.

California, which has long led the nation in providing access to high-quality postsecondary education, now has a degree-granting college program associated with each of its state prisons. Some of these programs are focused on the liberal arts. Others are more vocational in their curriculum. To ensure high quality, all are defined by the policies and practices of the affiliated colleges and must offer the curriculum and adhere to the standards in place at the college’s home campus. California’s extension of its higher education system to encompass all its prisons can and should be a model for other states to copy.

So many people in prison were locked up at young ages and never received the high-quality schooling we all deserve. Having missed out on so much, many are hungry for ideas, information and intellectual engagement. They need opportunities to grow and develop their considerable potential. When that happens, prisons will finally warrant the title “rehabilitation institution,” transforming them into beacons of educational opportunity.

This story is part of a collection called Education Against the Odds: Stories of teaching and learning under difficult conditions… with incredible results. Read more here. Also in Education Against the Odds, a personal essay from Alexander Hall, a former BPI student.