BPI alumni Jule Hall and Salih Israil, who are featured in College Behind Bars, spoke with Patrice Gaines along with the film’s director, Lynn Novick. This article, reproduced below, first appeared in NBC News.

The film fills the screen with stories about human transformation as cameras follow a dozen incarcerated men and women as they try to earn college degrees.

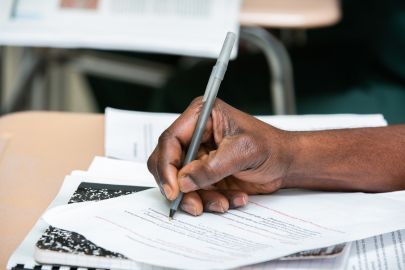

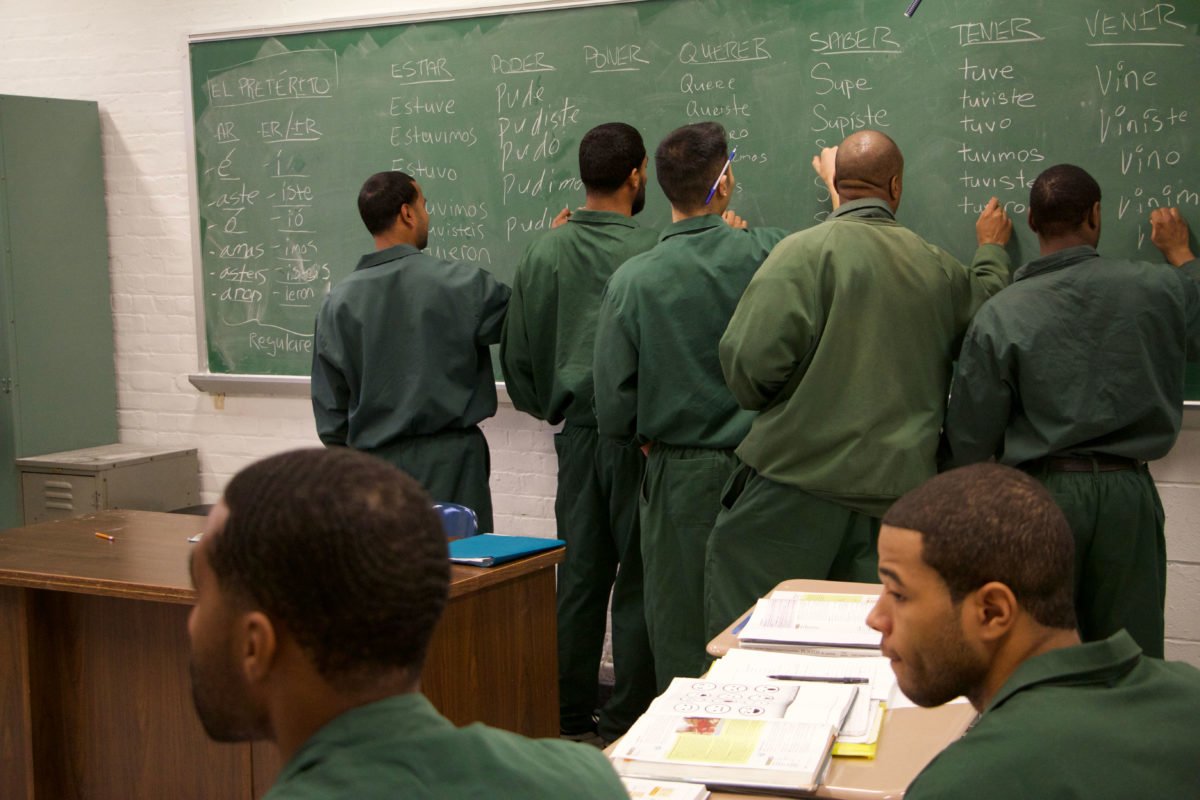

Bard Prison Initiative students conjugate Spanish verbs at Eastern Correctional Facility. (Skiff Mountain Films)

Jule Hall was 17 when he went to prison for being an accessory to homicide. For 11 years, he worked to be a perfect prisoner, broke no official rules or inmate codes, and focused on getting out. Then, he enrolled in the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI), a program of Bard College offering higher education to people incarcerated in six New York state prisons.

Hall recalls hearing a school administrator say, “‘From this point on, you should not look at yourself as a prisoner in this institution but as a student in a bigger institution.’ I thought he was crazy.”

But miraculously through education, Hall did begin to see himself and other inmates differently.

“There were guys in the Bard program with me that I would not have talked to, but seeing them in that (educational) environment started a process of me reinventing my identity,” he said.

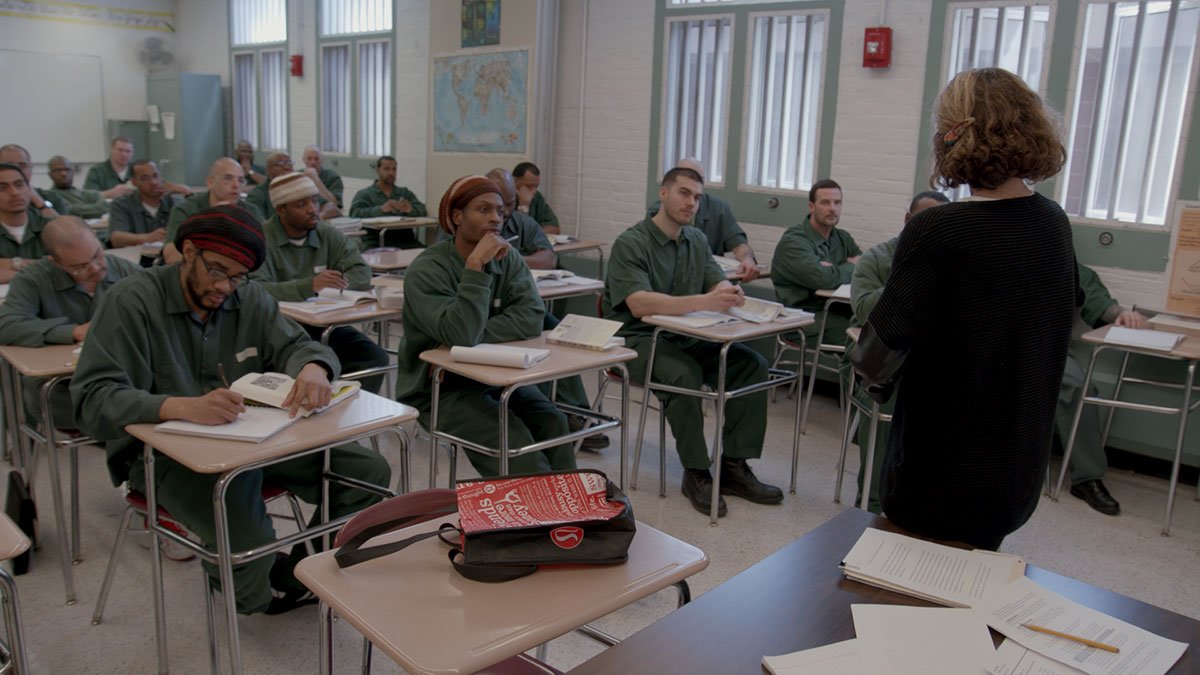

Bard Prison Initiative (BPI) students in a literature seminar at Taconic Correctional Facility. (Skiff Mountain Films)

Hall was charged in the 1993 killing of a mother who was stuck by a bullet while Hall and another teen were involved in a gun battle in the Brownsville section of New York. Hall served his time at the Eastern Correctional Facility, a maximum security prison in southeast New York. He was released early in 2015.

Now free, Hall, 44, who is a program associate for the Ford Foundation in New York City, is one of the people featured in the powerful new documentary series, “College Behind Bars.” The film fills the screen with stories about human transformation as cameras follow a dozen incarcerated men and women as they try to earn college degrees through BPI.

The four-part series premieres on PBS over two nights — Nov. 25 & 26. Like most people, Emmy-winning filmmaker Lynn Novick had not been inside a prison before she began lecturing and teaching at the Eastern Correctional Maximum Facility for men in New York State.

“I had a fundamental shift in what I think about incarceration,” she said.

One compelling storyline is the preparation of students on the Bard debate team and ultimately the team’s win over Harvard University debate team, a dramatic moment captured by media around the world.

For most prisoners, there is no access to a college program or a way to pay for tuition to take classes. There is currently only a pilot program introduced by President Barack Obama’s Education Department, involving 10,000 inmates across 64 institutions.

But new bipartisan legislation could take this program out of the pilot phase and reverse the more than two-decade-old ban on inmates using Pell grants, set by Congress and President Bill Clinton in 1994.

Bard Prison Initiative (BPI) students at Eastern New York Correctional Facility in an advanced bachelor’s degree seminar. (Skiff Mountain Films)

“There are millions of people in our country who are basically left out of the job market because they do not have the prerequisite skills. Restoring Pell grants to people who are incarcerated will equip them with the knowledge to meet requirements for jobs that exist,” said Rep. Danny K. Davis, D-Ill., a sponsor of the bill that will make the grants again accessible to inmates.

The United States has over two million people incarcerated and the documentary notes that about 630,000 people are released each year.

According to the Vera Institute for Justice, which has studied the current college pilot programs, access to higher education in prisons reduces recidivism by providing people with resources to be successful and strengthens families by helping formerly incarcerated people become economically stable.

Salih Israil appears in “College Behind Bars” as an adviser to students but he is also a graduate of the Bard program. Israil, 44, a software engineer in New York City, entered prison at the age of 23 as a drug dealer and served 20 years for robbery, assault and possession of a weapon.

When he entered prison in 1998, the “get tough on crime” legislation had halted college programs. But every man who had been able to attend college before the programs stopped advised Israil to apply if he ever got the opportunity.

“It was known that the people who went to college don’t come back,” Israil said, adding that many inmates experienced the changes and self growth that occurs when you receive a good education.

“I discovered I had ideas about things that I never knew I had,” he said. “I was shy. But I read books and had discussions with others. Inherent in that, I became a social person.”

Both Hall and Israil are optimistic about the impact the documentary series will have on viewers.

“I would hope the viewer sees the effort many people put into personal transformation and the role of education in personal transformation,” Hall said.

“We reduce people to what they have done,” Israil said. “I think what this film does is remind us that human beings are capable of changing over time.”

“College Behind Bar” premieres Nov. 25 and 26, 2019, 9:00-11:00 p.m. ET on PBS