University education programmes in prisons deliver inmates a brighter future and help reduce recidivism. Journalist Jesús Cabral is just one who has reaped the rewards of the innovative CUSAM in-prison education project. “I’ve had many moments of crisis since I got out, but I haven’t reofferend,” he explains.

The desk of Jesús Cabral, a journalist at the Tiempo Argentino newspaper in Buenos Aires, speaks volumes. Piles of articles about the country’s troubled present sit on top of photos and pamphlets, next to the mate he always offers. Several notebooks are filled with stories “for a book I’m writing about my life,” he says.

Jesús sits near the door of the newspaper’s office, which since 2016 has been a cooperative run by its workers. He greets everybody who crosses the door with a smile, and some hugs. Since President Javier Milei launched what some call a campaign against journalists seen as critical of the government’s policies, media outlets like Tiempo Argentino, whose small office survives a few blocks away from the President’s office, is a sort of space of resistance.

But Jesús, who writes about human rights and crime, among many other issues, is not just another journalist.

He has spent a decade in some of the most brutal prisons in Argentina. “At least half a dozen,” he says as he makes a mental list that he accompanies with his hand.

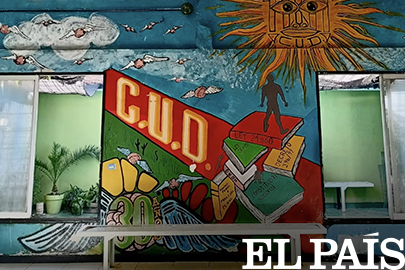

While inside, he survived torture and was one of the people who was involved in developing the CUSAM, a university programme that operates inside the federal prison of San Martín, in Buenos Aires Province – one of the most innovative in-prison education projects in the world.

***

Jesús was born in Pilar, about an hour from downtown Buenos Aires, during one of Argentina’s deepest economic downturns, a crisis that led to soaring unemployment and poverty in the late 1990s and early 2000s, which, experts explain, contributed to a rise in criminality.

The first time he was arrested, Jesús was just eight years old. He and some school friends had broken into a house.

“We started by stealing fruit from people’s gardens and then we wanted to see what there was inside, in the houses,” he remembers. When the victims told the school what they had done, police officers were sent in. “The handcuffs were falling off our hands because we were kids, and we were crying, a lot. I remember that.”

The scene was repeated many times. Jesús’ mother, who was a domestic worker trying to support her family, would pick him up at the station until, eventually, she stopped. Her son and his friends continued breaking into houses. One day, they found guns.

“Armed robbery was very different because it was all quick, you didn’t have to sell anything, you left cash in hand. I was 14 years old and I started robbing shops, houses, whatever. There is an adrenaline rush, an evil power that you get from all that,” Jesús recalls.

He again makes a mental list of the prisons he has been in. The number quickly reaches a dozen. In, out and back in again. He says that with each stay in prison he learned to perfect himself as a criminal, while gradually finishing primary and then secondary school.

“When you get out of prison, you are greeted by a society that is full of prejudice towards people who have faced imprisonment, a labour system that excludes you, there is no support. That generates a lot of anger. That and having been hungry, cold, tortured – all of that dehumanises you and it is very difficult not to replicate that kind of violence.”

—

In 2008, Jesús was transferred to the federal prison of San Martín, located in a marginalised area of Buenos Aires Province near an open-air rubbish dump.

A group of prisoners who had managed to finish high school started talking about setting up a high education programme and, eventually, the National University of San Martin, one of Argentina’s 62 public universities, started offering workshops and two diplomas: sociology and social work.

The project has grown over time. Today, it is estimated that around 1,000 people benefit from it. Another feature that sets it apart from other in-prison education projects in Argentina is that men and women, and even the guards, are able to study together.

Matías Bruno, sociologist and research coordinator of the CUSAM, says they offer sociology and social work because they want people in prison to have the tools to become active participants in their societies and so that, when they are released, its graduates can lead projects in their neighbourhoods.

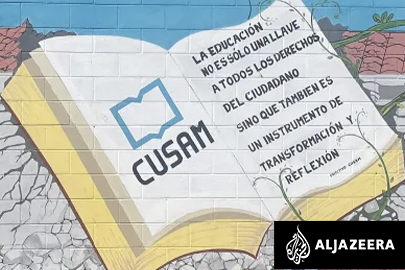

Education, Jesús argues, can have a transformational impact for the incarcerated.

“Prison is full of conflict. After being beaten up, you don’t want to pick up a book, but the university allows you to create a space where people are free, where they are taught that they are people, that they have rights, and they begin to see society in a different way. They prepare you for what is coming out,” he explains.

After his release in December 2012, Jesús eventually managed to return to journalism, a passion he had discovered in jail, where he wrote features about life behind bars.

“Writing gives me an opportunity to express myself, to communicate what is happening. When something serious happened in a slum [a marginalised neighbourhood], they used to send me because the newspaper needed that story and I had unique access to it because that’s where I come from.”

In addition, he continues to support people who are still in prison or had just been released by giving workshops, training and general advice.

***

People who are involved in in-prison education programmes say that they help to lower recidivism rates. Those who study and find projects to do when they are released are less likely to reoffend. In Argentina, a study by the University of Buenos Aires found that 84 percent of incarcerated people who received education did not commit another crime after they were released.

The phenomenon has also been documented in other parts of the world. A study by the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI) in New York, one of the world’s leading incarceration education programmes, and Yale University found that the more credits of study achieved, the lower the level of recidivism in the United States.

“Prison higher education programmes are very important in developing leaders who can then bring about structural change in their communities,” explains Dr Baz Dreinsinger, author and founder of Incarcerations Nations Network, an organisation that supports prison reform initiatives around the world, including higher education in prisons.

“The university education programmes in prisons in Argentina have particularly impressed me because there are so many of them. That and the level of empowerment of the students who get to develop as leaders and agents of change in their communities.”

Despite their popularity, many of the education in prison programmes in Argentina are facing major challenges in the context of large budget cuts to public education. In some cases, budgets have not been updated, which in a country with a high rate of inflation, means that their future could be compromised.

Many teachers, for example, say that the freezing of salaries makes their lives very challenging, and the lack of materials is a constraint for many students who, for example, cannot afford or access textbooks. This is in addition to the problems faced by the prison system as a whole, such as overcrowding, poor housing conditions and ill-treatment.

“What motivates me to continue, despite everything, are the real effects that a project like CUSAM has,” explains Bruno, the coordinator of the university’s in-prison branch.

“Someone who studies and does not reoffend is a triumph. It is someone who is not going to commit a crime. For me, education is the best security policy.”

Jesús says education has been lifesaving.

“I’ve had many moments of crisis since I got out of prison, but I haven’t reoffended. That’s what the university does. A society that is educated is one that cannot be defeated,” he explains.

Josefina is the 2024 BPI Global Research Fellow. In her role, she will spend her fellowship writing and publishing about budding and existing higher education initiatives in prisons across Latin America and elsewhere around the world.