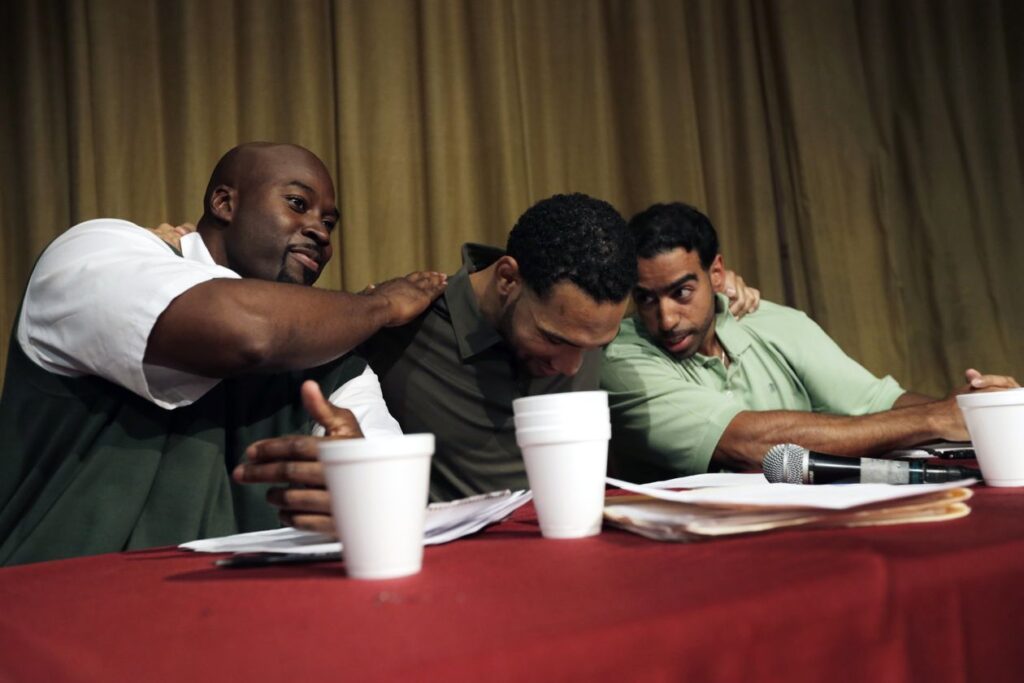

Reggie Chatman, 39, chats with Andrew Tang and Christoph Marshall, who are part of the debate team at the University of Cambridge. Chatman, who is on Bard College’s prison debate team, thanked them “for taking us seriously.” (Michael Noble for The Washington Post)

The three students from the University of Cambridge, wearing black suits and clutching sheaves of papers, stepped onto the wooden auditorium stage under the warm yellow lights. As members of a storied debate team, they had competed the world over but never in a place like this — a stripped-down hall in a maximum-security prison in Upstate New York that looms among the Catskill Mountains like a medieval castle.

In the center of the stage, three men wearing state-issued green pants and bow ties they had borrowed from their fellow prisoners stood ready to greet their privileged opponents. Only one of the inmates had finished high school before entering prison.

Reggie Chatman, a round-faced, fast-talking 39-year-old who has been imprisoned for murder since he was barely 18, grinned as he reached to shake hands with his Cambridge competitors. Once again, he and his teammates were about to attempt what, to an outsider, might seem impossible.

Yet it was here in 2015, at Eastern New York Correctional Facility in Napanoch, N.Y., that the prison’s debate team competed against Harvard — and won. The inmates’ underdog victory against the Ivy League school made international headlines, drawing attention to the need for inmate education programs like the one that produced the Eastern team, the Bard Prison Initiative through Bard College.

The debate team has since become a powerful symbol of personal redemption and penal reform. Friday’s debate came amid growing momentum for prison education; earlier this month, a group of bipartisan senators reintroduced a bill that would restore Pell Grant eligibility to incarcerated students.

But this time, the inmates were going up against one of the oldest and arguably the most prestigious debate teams not just in the nation but the world — a 200-year-old institution that has hosted speakers the likes of Winston Churchill, Ronald Reagan, Stephen Hawking and the Dalai Lama.

Students participating in the Bard Prison Initiative’s Debate Union program prepare for a match against University of Vermont in 2014. (Skiff Mountain Films/PBS)

Could the three incarcerated men, from a six-year-old debate team with no access to the Internet or to the world beyond their prison walls, outsmart the Cambridge team, ranked among the top teams at this year’s world debating championship?

The topic of the day’s debate: “This house believes that all states have a right to nuclear weapons.” Given first pick of sides, Cambridge would argue in opposition, while the Bard students would attempt to defend the proposition.

Chatman tried to play it cool as he thanked the Cambridge students for coming all the way to Upstate New York to debate his team, “for taking us seriously,” he said.

“People keep telling us, ‘Listen, these guys are really good. They start debating at four years old,’ ” Chatman said, laughing. “All the guys out there, they ask me about you guys. They’re like, ‘Are they going to be like James Bond?’ ”

Julia Wiener, 21, Christoph Marshall, 20, and Andrew Tang, 19, laughed with him

“He’s wearing the waistcoat,” Wiener said, pointing at Marshall. “He fits the stereotype.”

Then the debaters walked to opposite sides of the stage and sat down. Chatman looked down at his stack of notes, two inches thick. Then he looked out over the audience — eight rows of his fellow inmates in matching green jump suits watching him, waiting to hear him speak.

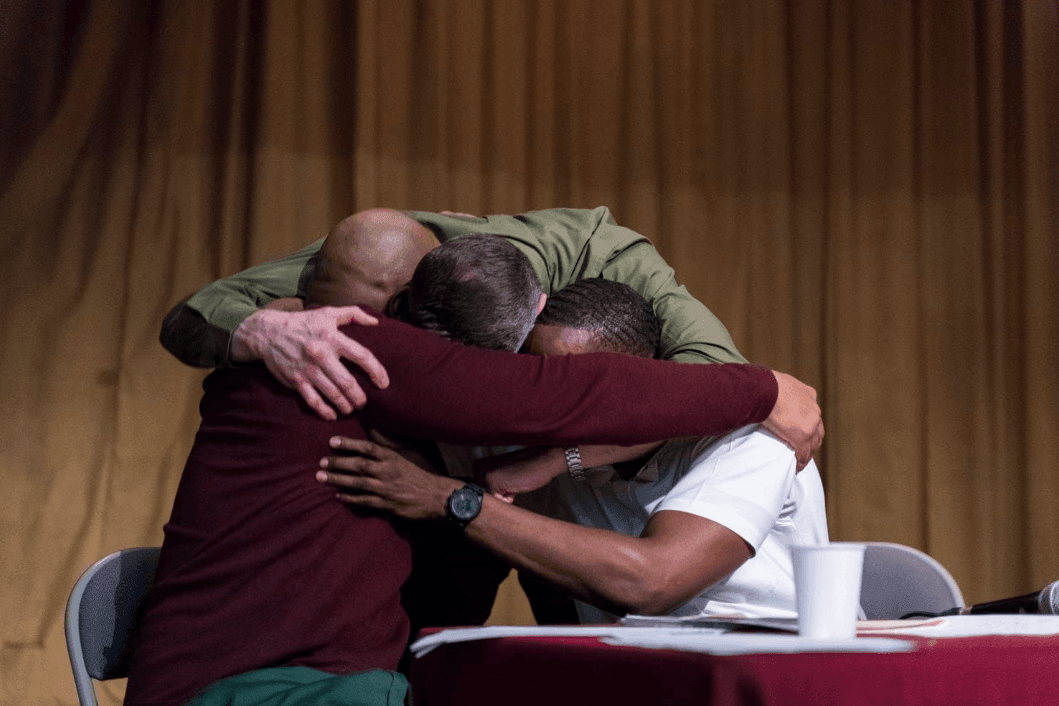

The Bard Prison Initiative team reacts to defeating Cambridge. (Michael Noble for The Washington Post)

The ‘counted out’

[His journey to a bachelor’s degree started behind bars]

Reggie Chatman was made for debate. Even as a young boy, he’d always loved to talk — at a galloping clip. He adored science and had competed furiously in football and basketball.

His favorite debate topic before debate became his sport: the NBA, with Chatman deftly arguing in favor of the New York Knicks and why Carmelo Anthony is “not as bad as they say he is.”

But education took a back seat as Chatman grew up in poverty in the Bronx and Rochester. His father was murdered when he was 10. He was put into a home for boys when he was 14. He had believed that a young black man could only become successful as an athlete, an actor or a “tough guy.”

Then, just months shy of his 18th birthday, Chatman fatally shot a 24-year-old man in Rochester whom he didn’t know, for reasons he would not discuss. He was sentenced to 25 years to life in prison for second-degree murder.

Once incarcerated, older inmates encouraged him as he earned his GED, discovered a passion for biology and started volunteering as an HIV educator. He is now on his way to earning a bachelor’s degree.

In the summer of 2015, Chatman was watching a debate at Eastern about whether to nationalize the pharmaceutical industry. While the judges deliberated, Chatman asked a question that prompted a drawn-out debate between him and the opposing school. Later that day, one of the Eastern debaters urged him to join the team. Two years later, Chatman would become one of the team’s star speakers.

He loves the rush he gets from performing before a live audience, from backing up a teammate on a key argument to seeking to understand the heart of a complex problem.

But the team has given him something deeper, he said, the belief that he is as worthy as anyone.

“Listen, with limited resources, human beings who have been counted out, who may have done some bad things, can do some great things,” he said.

[Amid a life of poverty and torment, a cello became his instrument of survival]

That’s also the message the Bard Prison Initiative hopes to send through its debate team, which has become one of the most visible success stories for prison education.

The program was founded in 1999 by undergraduate students at Bard College as a response to the 1994 law passed under President Bill Clinton that banned federal Pell Grant funding for prison education, causing many programs for incarcerated students to shutter. The Bard initiative now serves six prisons across New York, granting more than 540 associate and bachelor’s degrees and graduating alumni that have gone on to pursue advanced degrees at Yale and Columbia.

The debate team, which will be featured in a PBS documentary this fall directed by Lynn Novick, got its start six years ago. While teaching a public speaking class in the prison program, David Register shared stories with the students about coaching the Bard debate team. Soon the inmates began asking for a team of their own.

So in 2013, Register began meeting weekly with the students. The following year, he decided to invite the U.S. Military Academy at West Point to visit the prison for a debate.

To prepare, the Bard Prison Initiative students had access to only a few photocopied articles provided by Register — and whatever else they could find in the prison library.

The inmates were tasked with arguing that the federal government should not invest heavily in high-speed rail. They won.

“I was shocked,” Register said. “This was something special.”

Two years later, the news of the inmates’ 2015 win against Harvard went viral. Inmates from other prisons clamored to transfer to Eastern, motivated by a new vision of what was possible. For those on the team that year, the moment was transformative.

“I had broken unimaginable promises, the promise of my own future, the promise of what I could be,” said Elias Beltran, a recently released inmate who was on the debate team when it beat Harvard. “To be part of the team . . . it’s a way of proving that these promises weren’t completely lost.”

The prison debate team has lost only two of 10 debates so far, but beating the storied Cambridge team mattered to Chatman. It would be a big step toward “repaying my debt to society. . . . It would say that I’m getting there,” he said.

Limits as advantages

The Wednesday night before the debate, Chatman sat at the center of the classroom next to the two other speakers, whom The Washington Post agreed not to name due to safety concerns related to their cases. Facing the men were three fellow teammates who would argue against them for practice. When his turn came, Chatman grinned as he approached the lectern. Register asked him to pause before his speech to take stock of the opposition.

As the third speaker, Chatman is tasked with driving home all of his team’s arguments.

“What’s their main argument? Register asked.

“Their main argument is they have a path to Nuclear Zero,” or a world without nuclear weapons, Chatman said. Register asked him what the debate’s two main clashing principles were. “The ideas of morality and realism,” he responded as Register nodded.

Then Chatman launched into his speech, his voice getting louder and faster as his coach held up time cards each minute. As he sat down, the men around him pounded their knuckles on their desks — a team tradition.

After the practice debate had ended, one student in the back raised his hand, asking Register if he could look up a statistic about the number of deaths over 70 years of nuclear sanctions.

“I’ll run that in Friday morning,” Register responded.

Most debate teams would be able to Google that number on the spot, but the inmates have access only to the books in the prison’s library, to digital encyclopedias in the prison’s computer lab and to each other.

“I think we’re on track,” Register told the group. But inside he was nervous.

“This is actually the mystery,” Register said. “I go in the Wednesday before and I’m like, ‘We’re going to lose, we have no chance.’ And then Friday they show up and . . . they’ve thought through all the inevitable lines of argument.”

The inmates use their limits to their advantage, Register said. Unable to research online, they pore over the limited materials at their disposal, parsing every last word down to the footnotes.

Most importantly though, he said, the entire prison supports the debate team as though it were their version of a football team, with the 20-member debate team and other Bard students engaging in impromptu practice sessions while lifting weights in the gym, playing basketball, eating lunch in the mess hall as the rest of the inmates cheer them on.

That night in his cell, Chatman stayed up past 1 a.m. running through the arguments in his head. At the top of the latest draft of his speech, the inmate, whose friends call him “Reggie Mack,” decided to type a word in all caps for motivation: “MACK-NIFICENT.”

Nuclear Zero

Sitting at the far left of the stage on Friday, Chatman rocked back and forth slightly, taking notes as Cambridge presented its arguments.

So far, everything had gone according to plan. The first two speakers for Bard had argued that giving a handful of powerful states access to nuclear weapons, while denying these weapons to states deemed “irrational” or “unstable,” is elitist and promotes imperialism.

Cambridge then argued that these weapons can easily land in the hands of terrorist groups and rogue states and have the capacity to destroy the lives of unprecedented numbers of people. That the solution would be a world with no nuclear weapons.

“Nuclear Zero,” Chatman thought to himself, raising his eyebrows and smiling slightly, as he heard the Cambridge team make the argument. This was exactly what he had hoped, the moment for which he had prepared. Inside, he counted to 10, then breathed deeply.

When he got to the microphone, the words tumbled out as he fired off a list of rebutting points.

“Let’s say we accept their argument that there is a path to Nuclear Zero,” Chatman said. Since these technologies are already accessible, he argued, we cannot ensure that state actors will not take advantage of them.

“And so,” Chatman said, “in denying ‘othered’ sovereign states the right to acquire nuclear weapons, the elitist nuclear apartheid advocates for the true axis of evil, which is imperialism and the proliferation of global inequalities.”

He spit out the last words, unable to finish his last few sentences because the clock ran out. But, wiping the sweat off his forehead and returning to his seat, he felt confident.

After the last speakers finished, the judges left the auditorium to deliberate.

About 20 minutes later, the lead judge, Camara Hudson, stepped up to the microphone to announce the winner. She congratulated both teams on their performance.

Chatman’s eyes widened in his chair.

“At the end of the day,” Hudson said, “ . . . We gave the win to the proposition team, Bard College.”

The audience of inmates sprang from their chairs in a boisterous standing ovation. Chatman and his teammates embraced.

Hudson commended the frame that Bard College used in its arguments, “which is largely about the reality that denuclearization . . . is unlikely to occur in any world,” she said. “We don’t find a lot of explanation for how we can get to ‘zero’ from the opposition.”

Afterward, the two teams met once again at the center of the stage under the spotlights to congratulate each other.

“You’re world-class,” Wiener said to Chatman.

“I’m what?” Chatman asked her.

“You’re world-class,” Wiener said again.

Chatman looked at his Cambridge opponent and smiled. He asked what her team would do next. Wiener replied that they were going to spend the night in New York City, where they’d have fun and relax.

A few minutes later, she and her teammates put on their jackets and waved goodbye to Chatman as they stepped off the stage, the inmates applauding as they walked down the aisle and out of the auditorium.

On the stage, Chatman waited with the rest of the team for the guards to search them. Then he and the others would put their green jumpsuits back on and make the trip across the prison back to their cells.

This article appears in the April 20 edition of The Washington Post Social Issues section. Read the article at The Washington Post