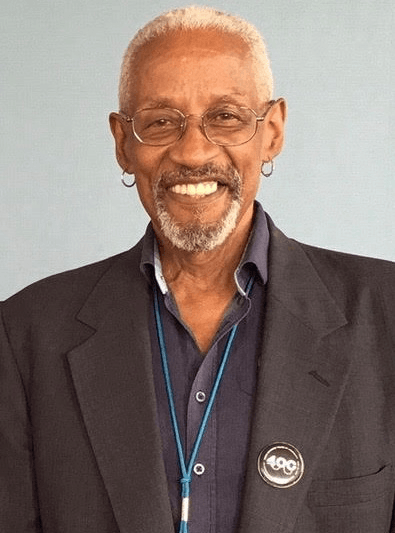

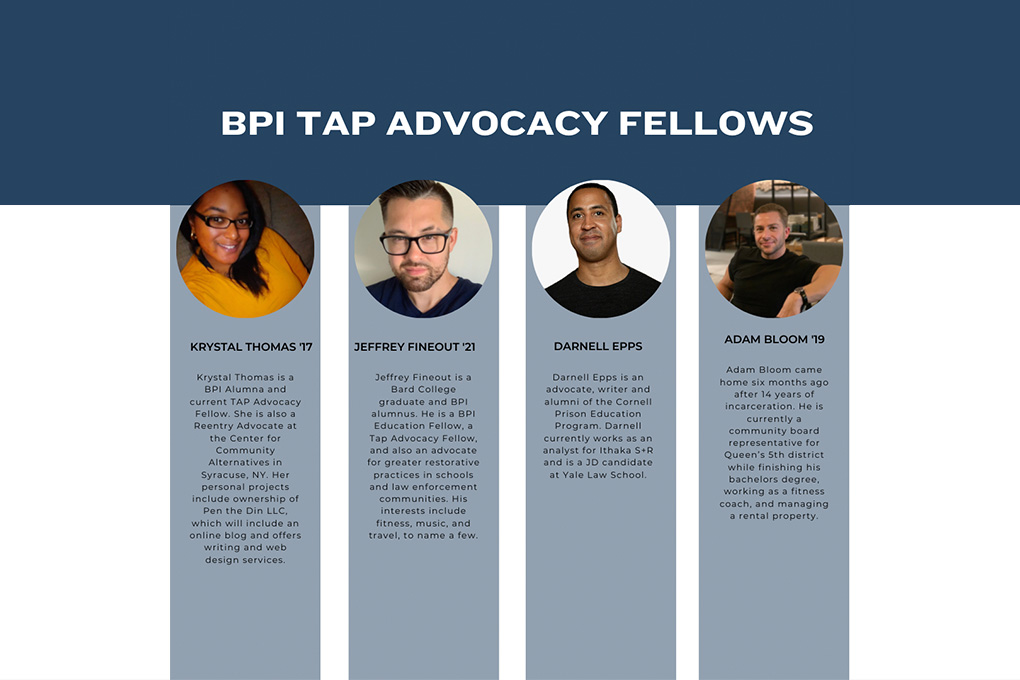

This reflection by Dr. Bob Fullilove, Senior Advisor to the Public Health Program, is part of the Community Voices op-ed series for the BPI Public Health Journal. Through the COVID-19 crisis, BPI alumni, staff, and faculty will be posting reflections about their work and response to the virus here on the BPI Blog.

The 1918 Spanish Flu epidemic has been frequently mentioned in a wide variety of media outlets lately. The comparisons between that pandemic and COVID-19 pandemic come easily to mind. From 1918 to 1920, approximately 50 million people died as a result of this viral infection, and the threat that this new pandemic poses might well rival 1918 as a substantial and major driver of social, economic, and political change worldwide.

What are lessons that we might learn from a review of that 20th-century pandemic? Perhaps the most important is the one we learn in studying how hard national leaders everywhere denied that such a calamity might befall us. In the last 35 years the planet has lived through HIV/AIDS, SARS, Ebola, and MERS and after each crisis waned, governments and policymakers failed to act on recommendations from experts that warned, “If nothing is done to prepare for the next outbreak, the costs in human lives and in economic stability will be huge.”

Evidence continues to mount that our failure to act on the recommendations that were made by public health professionals to anticipate and respond to the next pandemic threat is costing us dearly as we struggle with COVID-19 and its impact. After SARS, officials at the World Health Organization implored governments to improve the public health capacity to react to the inevitable wave of infectious disease epidemics of the future. As we look at all of the grievous errors that beset the US at this writing because of our failure to be prepared, one cannot help but wonder…what must be done to ensure that a repeat of this tragedy does not happen in the near future?

Interestingly enough, the answer may come about because of the dire necessity to completely abandon the logic of mass incarceration and the building of prisons. COVID-19 has revealed a tragic flaw in the need of human beings to congregate together in large numbers. This is a virus that exploits our tendency to create and function within groups. The more concentrated the number of folks who are clustered together in social gatherings, the easier this virus leaps from one host to another. “Social distancing” is a tacit recognition that our need to cluster facilitates the transmission of a viral infection.

If “clustering” is a risk factor for the transmission and acquisition of COVID-19 infection, prisons, jails, and homeless shelters must be understood as settings that have the tragic potential for facilitating the transmission of COVID-19. At this writing, a substantial number of organizations and individuals are clamoring for strong, positive interventions to lessen or remove the risk that those who are in prison – whether they are incarcerated persons or prison staff – must confront in this pandemic.

At this moment, the voices of BPI alums, particularly those who have studied or are currently working in some public health capacity, have particular strength. Most Americans are likely to subscribe to the notion that a person in prison is isolated in a cell with almost no contact with anyone else. Put in other terms, there is a belief that to be incarcerated is almost exactly like what folks who are quarantined or in social isolation are going through now with COVID-19. The reality of being herded together throughout the day in a variety of settings for a variety of reasons is a reality of prison life that is unknown to the average American.

For viewers of the documentary College Behind Bars, the real-time glimpse they get of the social settings that are created in prison facilities are critically important; it is clear to the audience that these settings can easily become the means through which a coronavirus infection can occur. Having created a set of viewers who now “get” the impact of incarceration on health and wellbeing, perhaps this becomes the moment when BPI faculty, students, and staff make clear to the rest of the world that part of the solution to the COVID-19 crisis starts with carefully rethinking, restructuring, if not dismantling altogether, the physical and social structures of mass incarceration.The message is clear, societies must completely restructure the places with the capacity to drive a dreaded pandemic.

How might we, as the BPI community, make that public health issue an active priority of us all? As this crisis worsens, as it inevitably will, these become the questions that we must address both individually and collectively. It is quite obvious that the time to move on this issue is right now.

Bob Fullilove

BPI Senior Advisor, Public Health Program

Professor, Sociomedical Sciences at the Columbia University Medical Center

Associate Dean, Community and Minority Affairs, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University