Initiatives like ours do more than provide access to high-quality education — they also provide a pathway for reimagining more effective and humane responses to crime and incarceration.

As thousands of students settle into the fall semester at colleges and universities around Boston, another group is preparing for an important milestone at a medium-security prison in Shirley. On Sept. 23 the first cohort of students from the Boston College Prison Education Program will don their caps and gowns and be greeted by a brass band playing the familiar refrains of “Pomp and Circumstance” before crossing the stage to receive their bachelor of arts degrees.

The ceremony marks a significant achievement, not only for students but also for Boston College. Our initial graduating class is small: Three students will be earning their diplomas. But the ceremony will start an annual tradition. Soon, our program will see groups of 10 to 15 students graduate.

Having worked within the criminal justice system for nearly two decades, and within college-in-prison programs for the past 10 years, I believe initiatives like ours do more than provide access to high-quality education — they also provide a pathway for reimagining more effective, meaningful, and humane responses to crime and incarceration.

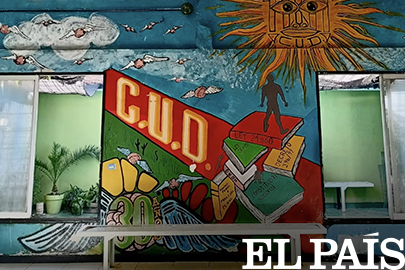

The university’s investment — financial and administrative — has been substantial, with college-in-prison aligning particularly well with the Jesuit dimensions of BC’s mission. Founded in 2019, our program initially admitted a group of 16 students, the majority of whom have since been released thanks to criminal justice reform. Now having admitted a total of 80 students, we’ve enrolled a new cohort every year (with the exception of the height of the COVID-19 pandemic), quickly growing to become the largest bachelor of arts college-in-prison program in Massachusetts and one of the largest nationally.

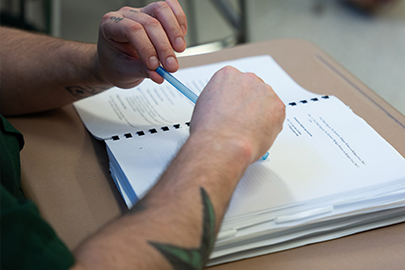

Our students study the arts and sciences along with employment-oriented coursework in entrepreneurship, strategic leadership, and personal finance. If students are released prior to graduating, the university supports them both on campus and online, helping them to complete their degree. Our first student graduating on the main campus in Chestnut Hill will do so this coming spring, two years after his release from prison in 2023.

This program benefits all who participate. I started my career as a criminal defense investigator at public defender offices in Washington, D.C., and then later worked at the Committee for Public Counsel Services in Massachusetts. From my time observing the courts and prison systems up close, what struck me was just how dehumanizing they can be.

Responding to crime at a societal level is a complex challenge, and I tend to be wary of easy solutions or sweeping claims. The criminal justice system often neglects that it is dealing with human lives. Most clients I represented found the experience of prison either chaotic and noisy or isolating and lonely. It is always easier to discard or ignore rather than to engage.

College-in-prison programs have the potential to provide a different approach. With new federal legislation supporting access to Pell Grants for incarcerated students, programs are sprouting throughout the country. Ours shares an affiliation with the Bard Prison Initiative, a leading international network of liberal arts programs in prison.

Many justify their programs through the lens of recidivism, the rate at which people return to prison after being released. The argument is that more education equates to fewer people returning. This is important and something programs should aim to achieve. But it also fails to capture the full scope of what is being accomplished.

Programs like ours provide not only economic and employment tools but also opportunities for students to develop and pursue interests; to engage in communities of mutuality and mentorship; and to reflect on their lives — not in a coercive or prescriptive fashion but on their own terms and within social and historical contexts. As a student once told me, “To make a human life in prison, that is the task.”

While the work of cultivating one’s own inner life is difficult (perhaps even impossible) to quantify, it is nonetheless a known experience, and one that can be deepened by exposure to the breadth and depth of a quality liberal arts education.

For many in prison, incarceration itself represents a major low point in their lives. College-in-prison programs can help students begin to rewrite that narrative. It can help them reconstruct their own identities in a way that helps them reflect on past traumas (and, perhaps, personal failings) and build healthier self-conceptions, ones that are not merely tied to their criminal record or their history of incarceration. The students in our program are far more than their past crimes and traumas. They are talented, insightful, and ready to contribute to society.

For our three students receiving their degrees and officially becoming Boston College alumni, the accomplishment is more than just personal. They are the first of many to follow. Their success demonstrates what is possible when society shifts its efforts from being purely punitive to adopting a more humanizing response to crime, one that ensures incarcerated people remain within the fold of our broader communities.

Patrick Conway is director of Boston College’s Prison Education Program (BCPEP), a partner of BPI’s Consortium for the Liberal Arts in Prison. With the support of BPI and friends of the University, BCPEP runs a college-in-prison program within MCI-Shirley.

This article was originally posted in The Boston Globe and can be found here.