In 2022, BPI launched the BPI Global Research Fellowship. Below is a summary of research conducted by the inaugural BPI Global Research Fellow, Ramiro Gual. Much of these ideas were later published in the European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies in 2023.

In Argentina, the widespread use of prison, regressive penal reforms, and overcrowding conditions coexist with the explosion of university-in-prison programs.

Argentina has more than forty-six million inhabitants. According to official statistics, more than 105,000 are in prison. The incarceration rate amounts to 225 prisoners per 100,000 inhabitants, triple what it was twenty-five years ago. Of the fifty most populous countries in the world, only nine have higher rates.

The country also has seventy public universities spread across its twenty-three provinces. Thirty-four have developed programs with periodically access to prisons to conduct research, offer degree programs and cultural workshops to incarcerated people. Twenty-five years ago, there was only one.

With the support of Bard Prison Initiative during 2022 and 2023, I conducted research in three of these experiences: the UBA XXII Program of the University of Buenos Aires, mainly its site in the Devoto prison (CUD), the San Martín University Center (CUSAM) of the National University of San Martín and the University Education in Prisons Program (PEUP) of the National University of Litoral.

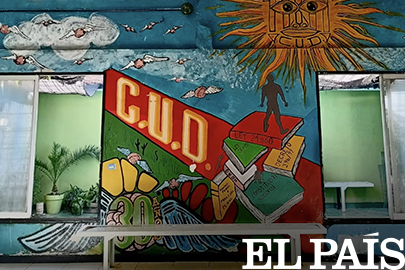

The UBA XXII Program is the oldest university-in-prison experience in the country. It began in 1985 two years after the return of democracy. With its founding site in Devoto Prison (CUD), in Buenos Aires, it has extended its intervention to other federal facilities located near the city. Since its setting up, it has offered weekly in-person classes that allow students to obtain the same seven undergraduate degrees as students outside of prison. It is also host to various cultural and research experiences.

The PEUP develops virtual degrees in three prisons located in the central-north of the province of Santa Fe. In 2004, in a local context of reformist prison policy, classrooms equipped with computers and Internet access were created in three prisons. Dozens of incarcerated students were able to join the same virtual education program that the university offered for non-incarcerated students. The program is possible because of the role a group of coordinators played inside the prisons, attending weekly and collaborating with the students in overcoming administrative, technical and educational difficulties, in addition to maintaining daily interaction with the prison authorities.

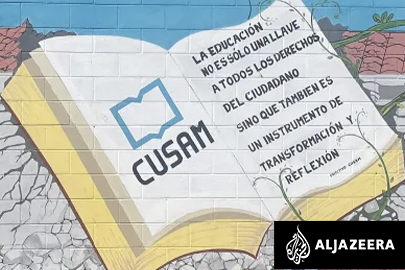

In 2008, the National University of San Martín landed in Unit No. 48 of the Buenos Aires Penitentiary Service with an in-person educational proposal: CUSAM. This decision is part of a series of closer ties between the university and the surrounding communities, many marked by high levels of vulnerability. The program is characterized by an extended coexistence between formal educational activities and cultural workshops, and the possibility of studying together men and women, incarcerated people and prison officers.

In these pages I would like to dwell on the capacity that these programs have demonstrated to build academic communities and their impact on the citizen identities that the students who participate in them manage to forge, influencing the living conditions within the prison and their individual and collective strategies when released. With citizen identities I mean the ability of students and graduates of these programs to participate in political, social, cultural and productive projects of a collective nature, during their incarceration and upon returning to their communities.

Inside communities

Despite their different contexts of emergence, the three university-in-prison programs have a common note: incarcerated people took the initiative to become students and promoted from the beginning these projects unrelated to the correctional proposal of the prison.

Marta is the founding director of UBA XXII Program, whose main site is in Devoto federal prison (CUD). With the return of democracy, she joined the management of the University of Buenos Aires, which sought to reorganize its academic life. She was leaving the rectorate’s headquarters when a woman asked her for assistance in getting her son to study. The peculiar thing was that the young man was imprisoned. That incidental event led to a first meeting with the group of prisoners, future students, inside Devoto prison.

Máximo, director and founder of PEUP, recalls the importance of a group of incarcerated who took law courses as off- campus students, when they managed to be temporary transferred to the university. He remembers one of them as a key actor by stating: “since there is this interest in studying, why don’t we try to achieve something more solid than what exists today? “

Also, in CUSAM experience, the desire of incarcerated people to become university students preexisted the will of the University, until it became a concrete demand. Penitentiary Unit No. 48 of José León Suarez was reopened in 2006 after overcoming corruption complaints, with no services other than the basic ones for the prison to be operational: food and security. The school classrooms had been built, but there was no primary or secondary education. In this new but abandoned sector, future students began by organizing drawing, IT and poetry workshops. Waldemar assumed the coordination of these workshops, served as a teacher in the reading course and consolidated the library with donated books. “In that world,” he recalls, “we began to think about the demand for university education.” A strategy supported by territorial actors from vulnerable peripheral neighborhoods, a key point to understand the link between the University of San Martín and the community, and between CUSAM graduates and their neighborhoods once they were released.

The consolidation of university-in-prison programs in Argentina is characterized by a deep determination of incarcerated people, then students. Marta remembers how quickly the borrowed classroom where the first university classes were taught in Devoto prison began to become too small. It was the students who, with their money and their labor, built CUD university center. “They lived on the construction site. There are scenes that are formidable. One serving mate, another knocking down a wall and the other reading a law note out loud,” she recalls.

Due to this initial determination and its origins from below (the incarcerated students) and from outside (the university actors), the university sites are consolidated as spaces within the prison, but foreign to it. Students and faculty perceive them as embassies, sanctuaries and oases within the prison. This foreignness is based on four pillars that, with variations, we can observe in the three programs. Self-management of space by incarcerated students, with reduced intervention from the prison administration. An academic proposal that differs from the correctionalist logic of prison. The emergence of external actors in the daily life of the prison. And the intention to take advantage of academic experience to influence living conditions in confinement. A university experience developed within the prison, but despite the prison.

From the beginning, CUD students created their own organization, with authorities elected in secret ballots and assembly instances. Its formalization, under the name Grupo Universitario Devoto (GUD), promoted the participation of students in political life, based on self-management, self-discipline, ideological plurality and responsible administration of resources. Requirements for membership, rights and obligations were established. The CUSAM students assume a similar organization, and while this research was developing an attempt at organization began to take shape in the PEUP university classrooms. When Mataderos was incarcerated, he had not a high school diploma. Upon learning CUD existence, he decided to complete his high school studies to become a university student. Meanwhile, he accessed the center as a collaborator, working without receiving remuneration. “I painted CUD. Using a knife as a screwdriver, I fixed the bathroom doors that were broken. The policy was ‘the guard on one side, we on this side’. If it breaks, we will repair it. It is self-management. It’s ours.”

From this foreign character between the university sites and the penitentiary structure, the members of the academic community – incarcerated students, faculty and university authorities – build an experience that distances themselves from the correctionalist spirit that runs through prisons. They also seek to move away from the ways of interactions incarcerated people construct to survive prison.

A sign impresses as soon as you enter CUSAM: “no berretines, my friend.” In Argentine prison culture, berretín represents the set of values acquired and consolidated within the prison that allow incarcerated people to survive it and position themselves as respectable members within the prison community. Under this motto, the leaders of the student group report (and warn) that the culturally constructed logics for interaction in prison (individualistic, distrustful, even extortionate and violent), will not be tolerated within the university site. There are two other signs that are equally symbolic: the initial one that states, “the university statute rules here” and the one that indicates that the CUSAM “was provided by the SPB (Buenos Aires Penitentiary Service) in agreement with the National University of San Martín.” If the prohibition of entering with berretines works as a warning for incarcerated people who decide to assume the role of students, the memory of the transfer of space and regulation through the university statute seeks to reinforce in penitentiary officers the demarcation line between the logics of prison and university. “Three logics shared the same space,” Isidro remembers, now graduated as a sociologist and university worker. “The logic of the penitentiary service, the prison logic of different wings and the university logic.”

The university sites manage to be spaces of alienation from the prison, also, by involving the university community in the daily life of the prison. If Erving Goffman managed to identify prisons, like any total institution, are characterized by limiting interactions to contacts between guards and incarcerated people, university-in-prison programs challenge that social world. The distinctive note of the programs in Argentina is its in-person development. The programs are sustained by the constant presence of external actors within the university sites in the prison. Just for the Law School, more than twenty professors enter the CUD weekly for teaching. PEUP is the only program in prisons that teaches its courses virtually. However, the presence of the program is guaranteed by a key actor: the coordinators, a role played mainly by advanced students and recent graduates in sociology, social work and law degrees. Guillermina, program coordinator at Las Flores prison in the past, defines her role as “carrying out the program. Let it work, be sustained and grow.” To develop their role, they establish “links between the classroom and the university, the classroom and the prison service, and the university and the prison service.” The coordinators, without restrictions from the penitentiary agency, register new applicants, carry out administrative procedures to guarantee their continuity in the program, and solve doubts in the management of the virtual environment and bibliographic content. They deliver study material, carry out the written evaluations scheduled by professors and process complaints for connectivity problems and the operation of the computers.

As a consequence of this external character from prison, university programs can aim to influence prison conditions. As Máximo Sozzo, director of PEUP, points out, the university program was conceived from its beginnings as an “application of harm reduction approach” caused by incarceration. We can observe a similar ethical and political positioning from the initial moments of CUSAM. In it 2008 founding document, they define educational and cultural practices “as an instance of problematizing the surrounding reality, of collective construction of knowledge and as a mean of humanization.”

The CUD’s founding documents do not contain similar statements of principles, but its practices have from the beginning included different interventions aimed at substantially modifying prison conditions. Legislative reform projects, collective judicial actions and forceful measures run through its history. Within the CUD, a group of law graduates who were still imprisoned created a free legal advisory service that helps incarcerated people in Devoto prison with their judicial procedures. In an office located inside the university site, they interview other incarcerated people, read together the notifications they receive, explain the general situation of their case, advise them and sometimes help them write their own presentations. Urquiza learned about the possibility of studying law while imprisoned thanks to that legal consultancy, which many years later he joined. “I went for a consultation about my judicial case, I arrived, and I said to myself: ‘This place is good.’ Meanwhile I went to high school and became more familiar with the experience.”

CUD, being a self-managed space, also provides shelter for other collective experiences that seek to impact prison conditions. This is the case of the first union of incarcerated workers founded in an Argentine prison, SUTPLA. Created in 2012, during its most active years it managed to influence prison labor policies, expanding access to work, improving salaries and safety and hygiene conditions in the prison’s labor workshops. Soldati joined the union shortly after his arrival at Devoto prison, understanding it as a way to give back to incarcerated workers what he received at the university center. “I have to take advantage of the space, that’s why I love CUD so much. The union was about being able to defend people like I have never been defended. I dedicated myself to that activity, and I understood that CUD gave me the tools to do that.” The legal advisory services and the union could not have existed if the university program was not created first. They also help to generate collective cohesion between prisoners who study there and those who do not, and function as an incentive for future students.

In the actor’s perspective, university sites greatly disrupt prison culture of individualism. Its high levels of autonomy, the relaxation of penitentiary control and the alteration of some classic principles of prison culture make possible the emergence of an alternative subjectivity that allows experimenting with new collective ways of facing prison. The university sites are identified by these actors as the few spaces where it is possible to build a different logic within the prison, more collective, largely associated with the generation of an academic community between incarcerated students without berretines and external actors who enter stripped of a correctional perspective. An experience that also impacts when returning to the community.

The return to society

University-in-prison programs are unique experiences, but returning to the community exposes students and graduates to the same pressing demands as other prisoners. Rebuild family relationships, secure housing, get a job.

Centenario managed to move forward in his IT studies within Las Flores prison with the PEUP. But “outside was different. Being released, look around and think: what’s next? I had nowhere to go.” He started washing cars, until he got an interview at an IT company. “They had me doing tests for three hours. Repair a disk, a video card, some batteries. How much voltage it works at, how it is connected. When they found out that I have been incarcerated, their confidence went away.”

In these extreme situations, higher education continuity is unlikely to appear as a priority on the horizon. Those who manage to do so must adapt to a university bureaucracy that works differently than their previous experience in prison. The university building and its logic are difficult to assimilate for released students. “Last time I got lost,” Congreso remembers. “I wasn’t going to come to Law School because I thought everyone came in suits. I was very disoriented.”

CUD students, upon released, must face this bureaucracy without clear institutional support. The same happens with PEUP students. In both examples, educational continuity remains in the hands of program coordinators who craftily overcome these institutional inconsistencies. This is how Comas, Centenario and España remember them with gratitude. “It is a question of the emotional bond of the coordinators, nothing more. The university does not have any program that is intended for the release.”

The situation is different in CUSAM. “It happens a lot that a student is released, and a week later he is in our campus office,” says Marcos, its director. “I call them, or they have to come for some procedure, but it is trying to close a circle. This is part of CUSAM, this is our office, it is your place too. You can come here to study, we’ll give you a tour, let’s have lunch.” A limited number of graduates continue to work at the university. Some do it in the in-prison-program and as professors. His incorporation into the faculty or other employment position at university is essential for Marcos. “It implies for the university a real transformation. CUSAM project is truly carried out if work possibility is also in the horizon, not for everyone but at least for some of them.”

The difficulty of obtaining a job due to having a criminal record is a recurring concern that no university program is in a position to banish. In PEUP and CUD programs, which have more options, many students opt for degrees that allow them to work as free-lance. Outside of these individual choices – valuable and understandable – each university-in-prison program serves as a breeding ground, in a more or less planned and extended way, for the generation of collective articulations after incarceration.

Esquina Libertad work cooperative was born in 2010 as a project on both sides of the prison wall. Despite the lack of institutional connection with the university, the project was born in CUD and its pioneer members were university students. Twelve years later, Paternal continues to remember with great pride his time at the cooperative. “It was born inside Devoto prison. It was made by incarcerated workers, and we functioned as a cooperative. We took it outside, and it grew.”

In 2018, based on an initiative with provincial funds known as Nueva Oportunidad, a group of PEUP coordinators and workshop leaders found the possibility of giving training courses inside Las Flores prison, with a rent for incarcerated students. In the midst of the pandemic, some students were released while coordinators and workshop leaders were prohibited from accessing the prison. This is how En Las Flores Cooperative was born. Despite being an initiative built outside the university institutional programming, this Santa Fe work cooperative is linked much more fluidly with the university than Esquina Libertad. En las Flores Cooperative collaborates in the repair of computers in the prison’s university classroom, provides computer support to students who are released and wish to continue their studies, and it is in negotiations to sign an institutional agreement with the university. For Carolina, one of its founders, En las Flores Cooperative “arose a little from the university, but it ends up falling apart and now we are trying to work together again.”

The collective experiences upon release find their most complete institutional shelter in the CUSAM. Lalo has been a territorial reference in San Martín since the 1990s. It was part of the movement of recovered factories in the midst of the economic crisis. Today he is the Territorial Development and Articulation Program Director of the university. He was finishing shaping Bella Flor Cooperative, created to incorporate those released from the San Martín prison into employment, when Eco Mayo Cooperative that brought together cirujas of José León Suarez had problems. Since then, the cooperative of cirujas and former prisoners has been one. “The cooperative supported the prison needing from day one. It sends to incarcerated people the things they need, whatever it can, and signs the needed documents for early releases.”

But the intersections between university, community and prison in San Martín are not limited to the cooperative. The horizon is also crossed, among other organizations, by a high school, a food center and La Carcova Popular Library. In all of these experiences, the university’s participation is much more explicit than in the cases of CUD and PEUP.

Waldemar was already a university student and the person in charge of CUSAM library when, during prison visits, he began to dream of creating a popular library in his neighborhood with his aunt. Upon released, they decided to settle in an abandoned area at the entrance to the neighborhood. The links between the popular library and CUSAM go back to its beginnings. Waldemar acknowledges having incorporated the knowledge about how to create and develop a library when he had to do it inside the prison. “Today we have this popular library because of the management experience that comes from CUSAM.”

La Carcova is much more than a space with books. In the library it is possible to get a high school diploma, workshops are offered for children, young people and adults and a good part of the neighborhood’s problems are managed. The first time I visited it was a hot November morning. During the hours that I shared in the library, Waldemar went out to look for a donation of food, he advised a young woman who approached asking about finishing high school, he received some former prisoners who were looking for the social workers of Patronato de Liberados and he put an unemployed young man in contact with another so that they could think of an alternative together. For Waldemar, the library is today “an educational and community organization reference. An educational coordinate of the neighborhood and the region. There are no libraries in slums, and we are a possible reference for a project to be developed locally, replicable in any other poor quarter.”

The links between the tools obtained and the subjectivities created within university sites in prisons and these collective experiences upon returning to the communities are evident. For Juan Pablo, former coordinator of Philosophy and Literature School at CUD, there is “a knowledge that is built and then has an impact on the construction of projects and a sense of the future. Knowledge in CUD always comes linked to other projects, institutional from the university, political, a social organization or a cooperative. This knowledge has organizational processes behind it that end up having a presence abroad.”

Build citizenship despite prison

In a 2016 paper published in Michigan Journal of Race and Law, Reuben Miller and Amanda Alexander offered the notion of carceral citizenship to describe the alternative citizenship trajectory that those with criminal records must experience. A concept developed to identify the consequences of mass incarceration in the United States and the pressing situation suffered by released people with the stigma of going through prison.

A central and negative element in the notion of carceral citizenship focuses on the network of formal and informal exclusions and sanctions to which people with criminal records are exposed. Sufficient stigma for an employer, landlord, or government authority to exclude them from a job, housing, or state license. The collateral consequences can be more severe in cases of more serious crimes and the effects can collaterally extend to their family members. In a later work published in Theoretical Criminology with Forrest Stuart, Reuben also managed to identify that doing time in prison can be a valued capacity to obtain employment in the social services sector and in the production of public policies against the most irrational penal system features upon returning to the community.

Exclusion and opportunity. Knowing closely the experience of university-in-prison programs in Argentina allows us to affirm that both elements are also present in the challenge that students and graduates face in forging their own citizen identity within the prison and upon returning to their communities.

Imprisoned students also suffer, due to their contact with the penal system, a series of impairments in access to their rights during confinement and upon released. Unlike Miller and Alexander research, in Argentina most of these limitations are not legally justified, but rather develop at the level of informality.

Transition through university programs in prisons, however, produces new subjectivities in some actors and allows a limited number of students to deploy new social, productive, political and community strategies during incarceration and upon returning to their communities. Throughout this investigation we have reviewed cases of students and graduates who, upon released, struggled daily without success to obtain a job, housing, and cover at least the most basic needs. These examples coexist, however, with a good number of released students who managed to successfully enter the labor market of their professions. Others were included in the university community, in some cases with formal jobs. Others continued to participate in organizations and agencies in the field of public policies committed to the transformation of the penal system.

The notion of carceral citizenship is extremely useful to think about the impact of university programs on the transit of their students within the prison and when they return to their communities. Students experience a transformation in their ways of exercising citizenship, negatively influenced by their time in prison, based on a series of exclusions and limitations. However, their active participation in university-in-prison programs seems to function on certain occasions as a successful antidote to stigma, producing new tools to confront the pains of incarceration and return to communities despite criminal records, and on certain occasions a good dose of capabilities and relationships that allow them to design productive, social and political strategies in their communities.

Ramiro is a Ph.D. candidate at National University of Litoral in Argentina where he also earned a Master’s Degree in Criminology. He holds a law degree from the University of Buenos Aires. He held the BPI Global Research Fellowship from 2022-2023 and is a member of the BPI Summer Residency 2022 cohort.