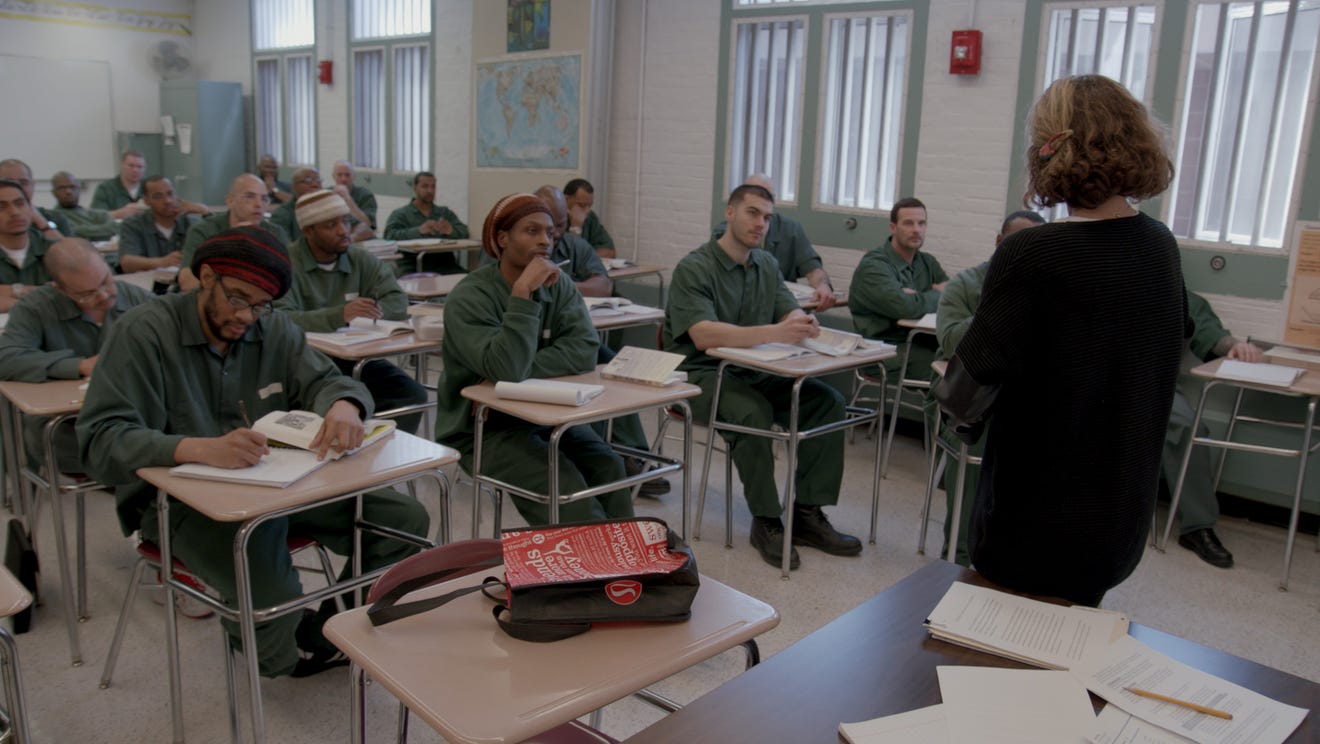

Bard Prison Initiative (BPI) students at Eastern New York Correctional Facility in an advanced bachelor’s degree seminar. Courtesy Of Skiff Mountain Films

PHILADELPHIA – Stacks of books are organized meticulously by genre amid the chaos of a maximum security prison. A makeshift desk made from cardboard is placed over a sink in a cramped cell. A chalkboard is filled with Chinese symbols in a room filled with eager students in green jumpsuits. Late night studying.

This isn’t the picture most Americans have of prison.

More often than not, violence, isolation and anger is what comes to mind. But these scenes from a PBS documentary airing later this month show viewers a different kind of prison life – the rigorous pursuit of pursuing higher education.

“College Behind Bars” follows students in the Bard Prison Initiative, a privately funded college program that began in 2001 in New York state prisons. For now, the roughly 300 students taking classes free of charge at the elite college are the exception. Most incarcerated individuals cannot afford a college education – and all are banned from applying for federal grants.

It wasn’t always this way. For decades, college prison programs flourished across the country. But after the passage of the 1994 Crime Bill, Pell Grants were banned for those who are incarcerated.

For the first time in over two decades, a push to lift this ban is sparking bipartisan support. Last month, Congress introduced bills to reinstate Pell Grant eligibility for those incarcerated as part of wider college affordability legislation.

For formerly incarcerated individuals, educational experts and prison reform advocates, it’s about time. They argue that postsecondary education behind bars will lower the likelihood that an individual returns to prison and benefit society as whole.

“Ninety-five percent of people who are in prison will get out,” Ken Burns, the executive producer of the PBS film, told USA TODAY. “Do you want them as responsible, tax-paying citizens, or people who have used their time in prison to hone their criminal skills?”

‘College Behind Bars’

Jule Hall is one of those people. Incarcerated at 17, Hall spent over 20 years in prison and is one of the main figures in the PBS documentary.

The film trails Hall, a 2011 Bard Prison Initiative graduate who earned a bachelor’s degree in German studies, as he navigates the parole process, is released from prison and enters the workforce.

Now, Hall works at the Ford Foundation analyzing the impact of social justice grants – an experience he describes as “another Bard” because of the experts and cutting-edge ideas.

“What BPI has achieved is exceptional, but I think it’s only a small part of what can be done if we get serious about this,” Hall said. “I want people to walk away from this film understanding that there are many more people who want to be involved in programs like this that are incarcerated, but they don’t have the access or the possibility of doing so.”

Access to education is at the heart of filmmaker Lynn Novick and producer Sarah Botstein’s vision. When the two screened one of their past films at a BPI class at Eastern Correctional Facility in New York, the engaging conversation they had with the inmates encouraged them to expose the program to more people.

“After that one experience in the classroom, we walked out and just felt like, ‘Oh my gosh, this is something everybody needs to know is happening,'” Novick said.

BPI students are felons serving long sentences for serious crimes. But Botstein said the filmmakers challenge viewers to rethink their views of felons by not immediately revealing the BPI students’ crimes, unlike most other films and books on the subject of college in prison.

In the program, the inmates are seen memorizing the opening section of “Moby Dick,” participating in classroom discussion on the ethics of stem cells and vigorously weighing the benefits of NATO as part of the viral debate team. To earn their bachelor’s degree, students must write a lengthy research paper that is comparable to graduate-level coursework.

This high standard of education – BPI is taught at the same level as Bard College, the liberal arts school in New York – is crucial to Hall’s hope of Pell Grant expansion.

“We need to be careful to make sure that the level of quality that we received with our education is kept intact,” Hall said. “When you provide education that’s high quality, it’s not just a benefit for the individual, but it’s a benefit for society.”

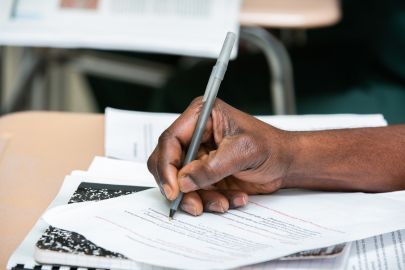

Bard Prison Initiative students conjugate Spanish verbs at Eastern New York Correctional Facility. Courtesy Of Skiff Mountain Films

Shawnta Montgomery is another BPI alum who is now working as a peer recovery coach at the Fortune Society, a New York City nonprofit focused on integrating formerly incarcerated individuals back into society. She said the film is meant to challenge the public’s perception of who deserves access to education.

“Should people in prison get this education?” Montgomery said. “Look what it does for people, look at the doors that are open, look at recidivism rates – you see the transformation.”

Numbers show benefits of college in prison

Education experts argue the benefit of expanding college prison programs is both personal and fiscal. Incarcerated individuals see their lives turned around by education. At the same time, the economy receives a boost from more productive citizens and reduced recidivism rates.

Lifting the ban on Pell Grants for those in prison may save over $365 million, according to a study this year by the Vera Institute of Justice and the Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality.

The study projected large benefits to reinstating Pell Grant access to incarcerated individuals, finding that inmates leaving prison will get jobs, contribute to the economy and will be less likely to go back to prison.

Nationally, about 68% of inmates released from state prisons were re-arrested within three years of release, according to a Justice Department study. In New York, where BPI operates, 42.6% of state prisoners released in 2012 returned to prison in the following three years, the state reports.

For BPI’s more than 550 graduates, the recidivism rate is 2.5%, the institute says. And it’s not just BPI: A 2013 RAND study found that inmates who took part in educational programs were 43% less likely to return to prison compared to those who did not participate.

“It’s not that often that you see such a clear narrative of this policy change,” said Casey Goldvale, who co-authored the study. “It will impact thousands of people’s lives, millions over time, and it also makes fiscal sense. It’s the best of all worlds.”

When the Pell Grant program started, it didn’t matter if an individual was in prison – everybody had access until the 1994 Crime Bill, said Cara Brumfield, who also co-authored the study. When that access was revoked, nobody in prison could afford the college prison programs and they dried up.

Lawmakers argued at the time that Pell Grants, a form of federal student aid for high-need college students, should not be spent on convicts.

Unlike other forms of student aid, Pell Grants are not loans and do not need to be repaid. For the 2019-20 award year, the maximum Pell Grant amount is $6,195.

“This isn’t about giving people in prison something new,” Brumfield said. “This is about restoring access to something that already existed and that was successful when the Pell program first started. This is about undoing a mistake.”

Prior to the 1994 ban on Pell Grants, there were over 300 college programs in prisons, said Tiffany Jones, director of higher education policy at The Education Trust. In 2005, over a decade after the ban, there were just 12.

Jones is hopeful change will come as policymakers realize tough-on-crime policies that exclude incarcerated individuals from opportunities don’t work.

“We are here because of the compelling stories of those that have been impacted and the fact that their stories of transformations and impacts aren’t exceptions, they are the norm,” Jones said. “There is this opportunity to convert compassion and concern into action. This is one of the very few issues where Republicans and Democrats are agreeing that action is necessary.”

Goldvale said the study found many at the local and state level are intrigued by the expansion of Pell Grants to prisons.

Asnuntuck Community College in northern Connecticut, for example, is feeling the effects of expanding Pell Grants to prisoners. The school admitted 320 incarcerated students in its fall 2016 class after receiving funding from President Obama’s Second Chance Pell program, said Jennifer Anilowski, the college’s interim director of admissions.

Many students earn certificates in manufacturing that are in high demand in the state, leading graduates to find work and immediately contribute to the economy. Now, the funding is continuing under the Trump administration – and Asnuntuck officials say they are happy to continue as long as the federal government allows them to.

‘It empowered me to realize I wasn’t a stupid kid’

Aaron Kinzel, a University of Michigan-Dearborn criminology lecturer, knows first-hand the significance of college education in prison.

As a child, Kinzel said he was violent and constantly exposed to illegal activities. Nearly killed by his stepfather, he turned to crime, and by 18, he was in prison after shooting at a police officer during a traffic stop.

While incarcerated, Kinzel cobbled together college courses as part of a Maine state program. One psychology class changed his outlook on life.

“That was the first time in my life that I really was empowered and felt kind of proud of myself,” Kinzel said. “For the longest time, I really didn’t understand the value of education. It empowered me to realize I wasn’t a stupid kid.”

Kinzel brings his students to prisons to humanize the criminal justice system. And when it comes to education behind bars, Kinzel said the debate boils down to a simple question.

“If I have someone coming home on parole, who do you want living next to you?” Kinzel said. “Do you want the guy that got education inside and is likely to get a job? Or do you want the guy that comes home with no job?”