The Bard Prison Initiative team has built an impressive record—and international reputation—since its unlikely 2015 victory

By Corinne Ramey

NAPANOCH, N.Y.—The Harvard College Debating Union wanted a rematch. The team had suffered a hard loss in 2015 to a group of talented debaters, drawing international attention.

So the Harvard team earlier this year sent an email, requesting another shot. It turned out their opponents, too, were seeking another contest after hearing stories about the legendary debate when their predecessors beat the mighty Ivy.

“I just googled, ‘what is their email, how do I reach out,’” said 21-year-old Rasmee Ky, an economics major who serves as the Harvard team’s president. “And it worked out.”

The opponents were Bard College students, albeit ones inside Eastern Correctional Facility, a maximum-security prison in upstate New York. The men, all of whom were convicted of state crimes, are part of the Bard Prison Initiative, which enrolls more than 325 inmates across seven New York state prisons. About 20 of them take part in the debate program. Friday’s rematch took place in the Eastern auditorium, before an audience of men in green prison garb, who gave approving nods and occasional cheers in favor of the home team.

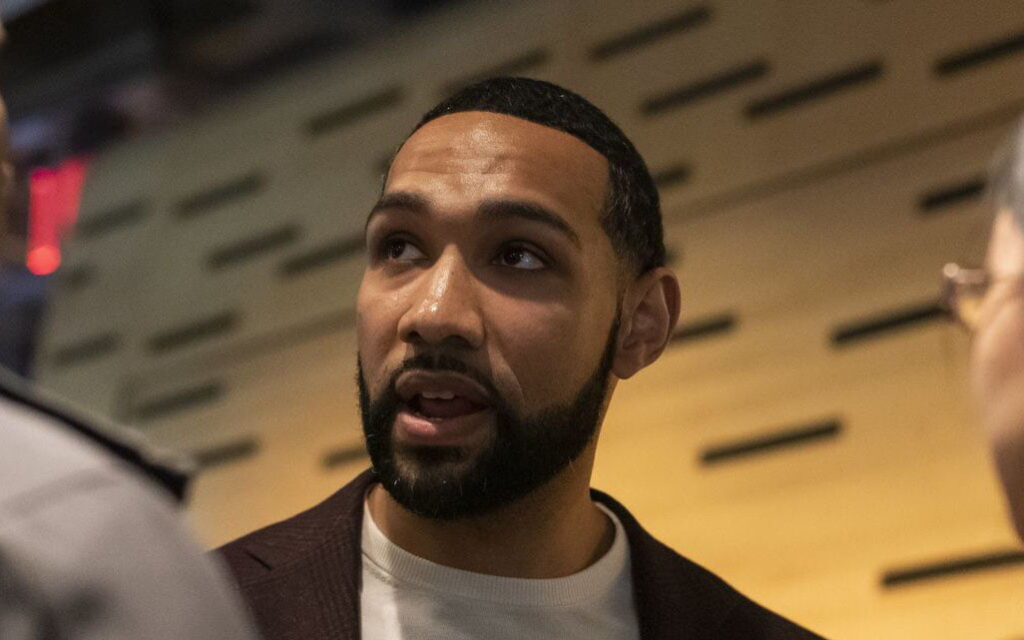

“It’s like having a football team,” said Dyjuan Tatro, who was a member of the team that defeated Harvard in 2015 and now works at Bard on the expansion of college-in-prison programs. He said when he was incarcerated at Eastern, correction officers and inmates alike rallied around the debaters.

After their Harvard win, the prison team continued debating twice annually, besting teams from Brown and Duke universities, and suffering a loss to the University of Pennsylvania when debating whether the U.S. should provide monetary reparations for American Indian boarding schools. Coach David Register chalked up the team’s 12-4 record to obsessive preparation, teamwork and more life experience than most of their opponents.

Both sides had prepared for months ahead of Friday’s contest. The proposition being debated: The corporatization of higher education does more harm than good. Harvard, as the visiting team, chose to argue in favor of that position.

At the beginning of this semester, Mr. Register handed his debaters—who don’t have online access—a couple of books and 400 pages printed off the internet. The debaters also asked their friends and family to print out articles and recount YouTube videos they watched on the topic.

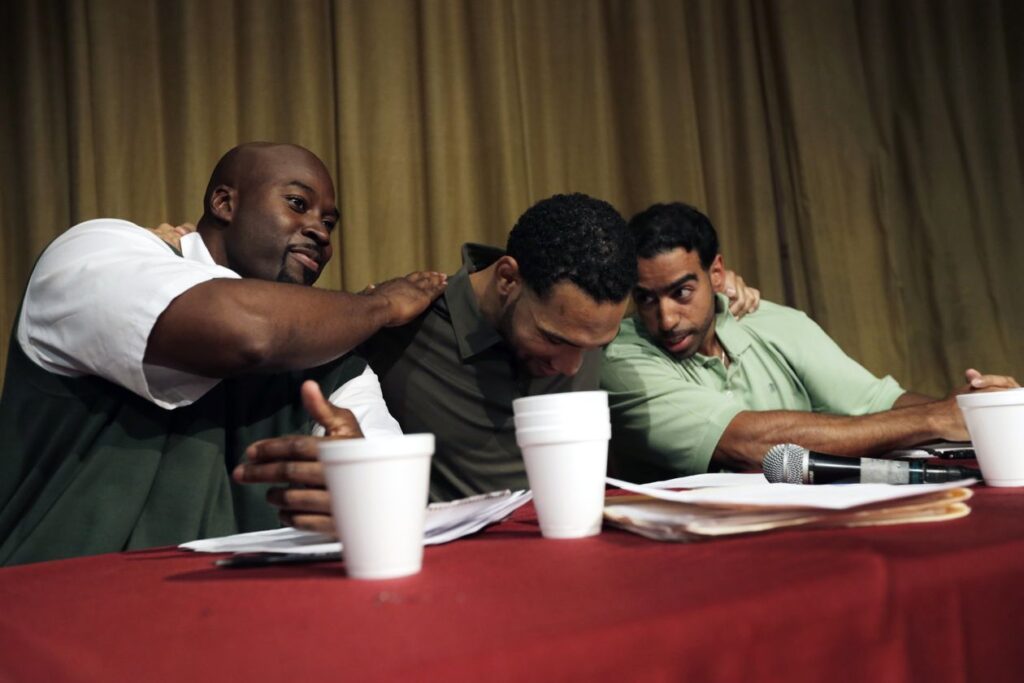

During weekly sessions, they rehearsed arguments and discussed strategy. Outside of class, fellow inmates quizzed the debaters to help them prepare.

“The last two days were crazy,” said debater Ricardo Mendez, 30, who is majoring in literature and the humanities. “Guys were constantly stopping me, saying, ‘Yo, why is corporatization good for this?’”

Back in Massachusetts, Harvard students discussed strategy and framing, and assigned each debater a specific focus. “Above all it’s googling,” said 22-year-old debater Andy Wang, who majors in social studies and philosophy.

Ms. Ky, the Harvard team president, said the debaters had prepared for potential attacks by their opponents.

“There are ways the Bard team could frame us as being out of touch with what is happening within higher education generally,” she said. “Our school has much more funding than the typical higher education institution.”

Friday’s debate came as college-in-prison programs have grown. In the 2021-22 academic year, more than 13,000 inmates enrolled in college programs across the U.S., up from 6,000 in 2016-17, according to the Vera Institute of Justice, which has pushed for increased funding for such initiatives.

The debate over college in prison, once focused on whether it should exist, has shifted amid expanded funding and a recognition that most prisoners will re-enter society.

“Now the fight is about what college in prison will be,” said Max Kenner, Bard Prison Initiative’s executive director. While some institutions, notably Ashland University, a private Christian school in Ohio, have focused on a broad expansion allowed by remote learning through tablets, others like Bard have advocated for in-person classes of a comparable level to those at undergraduate colleges.

The prison debate team members this year took classes including “Principles of Microeconomics” and “Southern Global Feminisms.”

On Friday, debaters on both sides spoke rapid fire, throwing out statistics on the fly.

“We believe education is a public good,” said Ms. Ky, who proceeded to argue that when universities focus on economic bottom lines, it ruins education.

The prisoners argued that colleges were failing due to dwindling public funding, and that partnerships with corporations led to internships and jobs for graduating students. “We believe corporatization…is setting us on a path to a more equitable society,” said Dhoruba Shuaib, 31.

The proceedings were at times heated. When a Harvard debater eagerly raised his hand, one of the prisoners told him patiently, “I’ll get to your question in a minute.” A Harvard student accused his opponents of having “a gaping hole in your case.”

After an hourlong debate, the judges—two professors and a debate coach—left the room to deliberate.

They called it for Harvard, by a 2-1 vote. But it was close, one judge said, adding that the Eastern men had been required to argue what seemed the tougher position.

The prisoners were disappointed. “Boo,” one correction officer said, after hearing the outcome.

Still, there was an upside. “Now that Harvard won,” said 48-year-old team member Leroy Taylor, “there has to be a rematch.”