Conservatives and liberals who clash on just about everything else agree that the harsh drug sentencing laws that swept the country starting four decades ago have been wholly counterproductive, driving up prison costs to bankrupting levels, undermining confidence in justice and decimating communities.

But as Congress seeks to reform federal sentencing policies, it should revisit other outdated policies that trap people with criminal convictions at the margins of society — and indeed have driven many of them back to jail — by denying them jobs, housing and education.

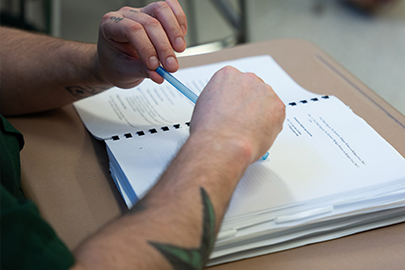

The Obama administration did just that this week, creating a pilot program that will allow a limited number of inmates to receive federal Pell grants to take college courses behind bars. It will last three to five years and be open to inmates who are eligible for release, giving priority to those scheduled to be released within the next five years.

The program, created by executive authority since Congress closed off access to Pell grants in 1994, is cast as an “experiment’’ to gather evidence on how education affects recidivism. But mountains of data already show that inmates who receive college degrees in prison — or who only participate in prison education programs — are far

Congress was incapable of hearing that message in 1994, when it was ratcheting up criminal penalties under the misguided belief that people who commit crimes deserved to be permanently exiled from society’s mainstream. Among its other dumb moves was to revoke inmate access to Pell grants in federal and state prisons. Congress left the impression at the time that inmates were eating up an undeserved share of student aid when, in fact, they received fewer than 1 percent of the grants.

The move had a disastrous impact on prison college programs. About half shut down. In many states where the programs survived, costs were shifted to inmates or their families, or were underwritten by private donors or foundations. Though underfunded, these programs did a world of good.