Anyone looking for something to watch over the Thanksgiving Holidays would do well to check out the inspiring and fascinating “College Behind Bars,” airing on PBS stations on November 25th. An extended trailer can be viewed here. The show focuses on one particular college-in-prison program, the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI).

BPI is part of Bard College, a small, private university in New York State. It enrolls just over 300 students, all of them serving time inside six different New York State prisons.

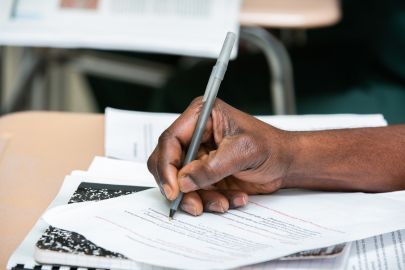

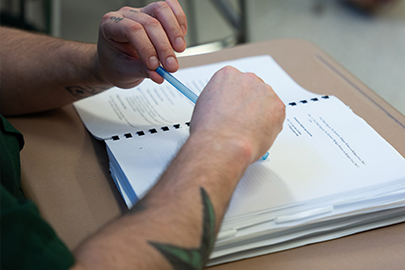

The show is four hours long, but the stories of individual prisoners and the program as a whole are gripping. One of the most interesting things about BPI is the very high level of the college courses taught there. Rather than remedial instruction, the students are learning about The Brothers Karamazov and high-level mathematics.

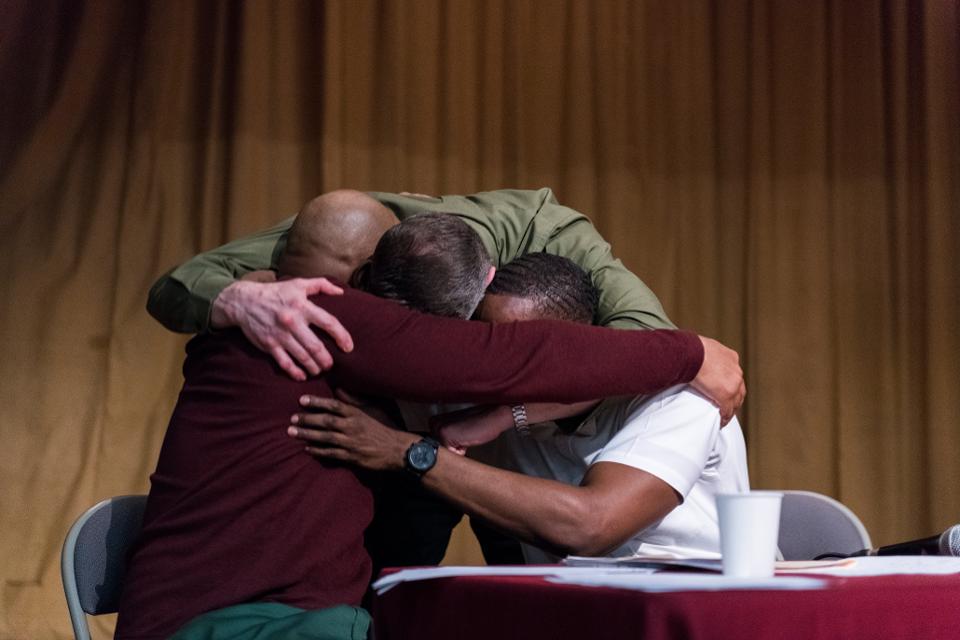

NAPANOCH, NY – APRIL 19: The Bard Prison debate reacts to defeating the Cambridge University debate team at Eastern Correctional Facility. Cambridge University, is the world’s top ranked debate team. Cambridge was invited to come to the prison and compete against the the Bard Prison Initiative. (Michael Noble, Jr. for The Washington Post via Getty Images)

Twenty students at a time also learn to debate. And they learn to debate well. The BPI debate team regularly challenges teams from the best colleges in the world. They have beaten the likes of Harvard, Cambridge, and The University of Pennsylvania, debating issues such as undocumented immigration, the desirability of high-speed rail, and abolishing the electoral college. In fact, the only teams to ever beaten the BPI team, which has a 10-2 record, are Brown University and West Point (and the BPI team won three subsequent re-matches with West Point.)

The students at BPI are not generally low-level offenders who wound up in prison through bad luck. These are mostly men and women who committed serious crimes and are serving long sentences. These are folks who under normal circumstances would be highly likely to end up back in prison after their release. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, over two-thirds (67.8 percent) of released prisoners were rearrested within three years of release and over three quarters (76.6 percent) were rearrested within five years. The statistics for BPI graduates are much, much better. 97.5% of them never go back to prison.

It is natural that some object to college prison programs because people who did bad things are getting a free education while so many law-abiding citizens cannot afford to go to college. But such thinking is short-sighted. According to The Wall Street Journal “The average annual cost for each person in a New York prison is $69,000, by state data, and . . . The Bard Prison Initiative says its college program costs about $9,000 for each student yearly.” In other words, a successful prison college program saves taxpayers an enormous amount of money. This is money that could be used to expand college access for everybody.

Of course, there is the question of whether programs such as BPI can be scaled up to make any sort of real dent in the recidivism rate or the role that released prisoners can play in society. As noted, BPI enrolls 300 students at a time, but over 10,000 ex-prisoners are released from America’s state and federal prisons every week. Most of BPI’s students entered prison when they were still minors, so they hardly entered the college program with a strong educational background. And many prisoners suffer from serious mental illnesses that would make giving them a high-quality college education extremely difficult.

So can the BPI program be scaled up to meaningful numbers? I had the opportunity to speak with two BPI graduates about these concerns. They were both articulate men with professional demeanors. They were both adamant that they are not outliers and that BPI-type programs can elevate the great majority of prisoners. One said, “I am not an exceptional person. I’m a person who was given an exceptional opportunity.”

So how does BPI do it? There seem to be several answers. One is high standards. The documentary shows very high levels of class discussion and students talk about their intense efforts, sometimes spending hours on a single page of reading. Another is respect. One student effused that “They didn’t treat us as problems to be fixed.”

Another key is optimism. Hope is doubtless something in short supply. BPI tapped in prisoner’s need for that. As one said, “Inmates are longing for hope and hope materialized in the form of education.” Also important are the role models that the professors teaching these course provide. As one graduate put it, “Our interactions with the professors modeled our interactions with our future bosses.”

America is having a healthy discussion about mass incarceration, but much of the rhetoric is steeped in wishful thinking. Listening to some politicians and activists, one would think that our prisons are mostly filled with non-violent prisoners serving long sentences for little more than smoking a joint. On the contrary, while there are plenty of drug dealers in prison, most people in state prisons are serving time for crimes such as murder, rape, assault, robbery, manslaughter, and burglary. If this country is going to be serious about reducing the number of incarcerated people, it must be serious about reducing the recidivism rate for people who have committed major, often violent crimes. They deserve to serve time, but they also deserve a chance to redeem themselves. BPI and similar initiatives show a way forward.