Courtesy of Skiff Mountain Films

Lynn Novick’s four-hour PBS documentary about the Bard Prison Initiative and the impact of educational programs as part of prison reform is provocative and inspiring.

It’s rare that a week passes without some buried news story about states cutting back on prison education programs or even the availability and convenience of books. These measures, sometimes part of cost-trimming and sometimes part of increased privatization around prison services, come even as more and more reports and studies argue that education in the prison system actually leads to lower per-prisoner costs and that those programs are associated with dramatic reductions in recidivism rates.

If you lack the time to read those studies or just prefer human stories to statistics, Lynn Novick’s four-part PBS documentary series College Behind Bars is persuasive and compelling as an argument for prison education reform (and general across-the-board prison reform), but more than that, it’s so humane and emotional that it will probably have you brushing away tears as you’re pondering bigger questions.

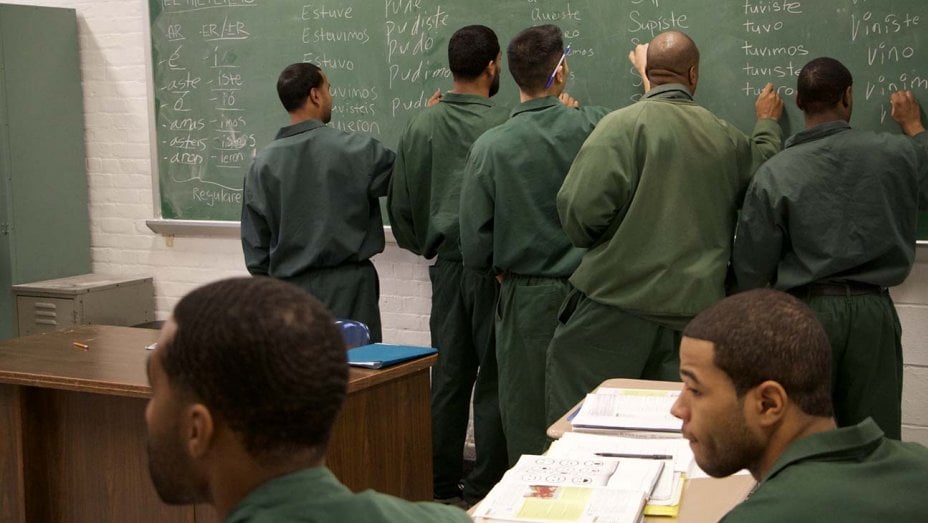

Novick, revered in the PBS sphere for her collaborations with College Behind Bars executive producer Ken Burns, focuses on the men and women incarcerated at New York prisons participating in the Bard Prison Initiative, an innovative and rigorous program giving inmates the opportunity to pursue AA and BA degrees.

The four hours, premiering over two nights and yet easily binge-able as well, are designed as a steady escalation of expectations for the BPI program, while at the same time exposing audience expectations and condescension. We start off hearing about how the inmates are taking the same courses as their Bard College equivalents, and I think there’s a “Oh, that’s nice” response that runs the risk of seeming dismissive, until you see the inmates learning calculus and Mandarin and recognize the real commitment. Then you see the inmates, as part of a debate extracurricular, going head-to-head with forensics squads from West Point and Harvard and your appreciation rises to a, “This is really impressive” level.

By the time you get to the second half of the series and you watch these students working on the 80- to 100-page senior papers, defending their theses to professors and attempting to do genuine scholarly research with limited access to materials, erratically available time and the ingrained pressures and threats of the penitentiary system, you’re likely to go from respectful to astounded. I know I was.

Following students, men and women, at several maximum- and medium-security prisons, Novick is able to train her gaze on at least a dozen inmates who are candid in their fears and aspirations. Some are nearing the end of long sentences and hoping their Bard degree with help them upon their release, others are years from any hope of parole and simply trying to get value and meaning out of their incarceration and this rare opportunity. All are engaged, committed and straight-up passionate about the things they’re learning and just having this chance to learn, a chance many or most of them never would have gotten in their civilian lives. Novick distributes facts and figures throughout, positioning BPI within the context of ongoing debates about what taxpayer money should be supporting in the prison system, what private entities could or should do to help and, on the broadest and deepest level, what we think the purpose of the prison system is at all.

I suspect that if you’re of the opinion that prison is exclusively about punishment and not, to any degree, rehabilitation, College Behind Bars will have a lot of work to do to shift your opinion, but it also showcases the personalities capable of making those changes.

It’s remarkable how quickly College Behind Bars solidifies its emotional bonds to its primary subjects. Over four hours, your heart with break and your hopes will soar for inmates like Jule, the first of the incarcerated students to get to return to a world of freedom he hasn’t experienced since before 9/11; or for Dyjuan, whose brother has been incarcerated at a facility without access to BPI or a comparable program, or for Tamika, whose mother stubbornly rejects the idea that “free education” is a thing that prisoners deserve.

Over the series’ running time, the inmates let us into their cells and recount their own histories, as Novick calculatedly resists telling us about their crimes up-front, making that only a piece of their stories and not the totality. These are not, for the most part, petty criminals, and although there are threads of injustice that run through some of their pasts, this isn’t a parade of wrongfully accused innocent men and women. A common thread of “falling in with the wrong crowd” runs through many of the stories, not as an excuse or justification, but as a parallel to the importance of community-building in the BPI program. This, the series displays frequently, is what happens when those without previous opportunity or privilege fall in with the right crowd.

With producer Sarah Botstein, Novick filmed College Behind Bars over four years, but it occasionally becomes confusing when it tries to cut between character arcs and different groups of inmates in a way that implies linearity that doesn’t always exist. There are also clear gaps in her access. One of the most interesting running background threads is the tension between BPI students and non-BPI inmates and, particularly, between BPI students and the guards who may feel that these inmates, now surpassing many of the guards in advanced education, are getting special treatment. There are no interviews with guards (their union declined) or with specific prison administrators — Anthony Annucci, acting commissioner for the New York State Department of Corrections, has to speak on behalf of a lot of official entities — or with non-BPI inmates. We’re given only limited exposure to the potential struggles and failures of inmates once they’re accepted to BPI.

These are minor quibbles exposed more in retroactively considering College Behind Bars than while actually watching it, when the levels of emotional commitment and inspiration predominated. This is a project of substance and importance, but also remarkably a series that could be watched with the family during the holiday season to spark conversation and instigate a better understanding of a segment of the population that it’s easier to stigmatize or just ignore.

Airs: Monday and Tuesday, 9 p.m. ET/PT (PBS)