This reflection on teaching in the pandemic by Bard Microcollege Holyoke Program Director Ann Ward is part of the Community Voices op-ed series. Throughout the COVID-19 crisis, BPI alumni, staff, and faculty and Bard Microcollege students will be posting reflections about their work, studies, and response to the virus here on the BPI Blog.

I like to think I’m pretty great at spotting fake news, but the new reality we were dropped into in mid-March didn’t exactly create a healthy environment for critical thinking. The world retreated into quarantine, and Bard Microcollege Holyoke faculty, staff, and students would be completing the semester remotely. While I dreamt that working from home could mean finishing my novel, reading for pleasure, and mastering sourdough loaves, our first few weeks were a haze of frustration, fear and denial: a bored toddler snowed in, running out of peanut butter crackers. So, when I saw a fake news article about dolphins returning to the canals of Venice, I believed it. Why not? It infused quarantine with a kind of beauty, instead of that constant humming terror.

The last time I met with my Digital Literacy students at Bard Microcollege Holyoke in person was March 9. The first sentence of my course description would prove a little more apt than I intended: “Gifs, Facebook, conspiracy theories, baby sharks: the digital landscape is embedded into our daily lives – the more skilled we are at navigating it, the better.” Everyone was uneasy, teetering between rational panic and frustrated denial. I wiped down the desks with Lysol before the students arrived in the third-floor classroom. (Two months later, students would tell me they wished they had three flights of stairs to climb, a little forced exercise, something different to do.)

We had already studied John Suler’s “Online Disinhibition Effect” to understand the psychology of trolls. We dissected the rhetoric of memes and created our own. We studied circuits and binary in that last in-person class, sticking pink electrical tape to batteries, some students moving quickly, their light bulbs flickering on and off with a snap of a switch.

But then we were remote, and it was time to learn about fake news and conspiracy theories. Normally when I teach this, students read about the “Sandy Hook Truther Movement” – a heartbreaking theory, spread by Alex Jones, that the Sandy Hook elementary school shootings were a hoax. But I couldn’t assign that – I couldn’t bear it. We were all more isolated than ever, and didn’t need the extra darkness.

False information about the virus was spreading rapidly – some of it was absurd or wishful thinking (“can putting hot peppers in my food prevent or cure COVID-19?”), but most was harmful, racist, and ableist. We sent students resources to combat misinformation and watched as the World Health Organizations’s myth busting page grew longer and longer.

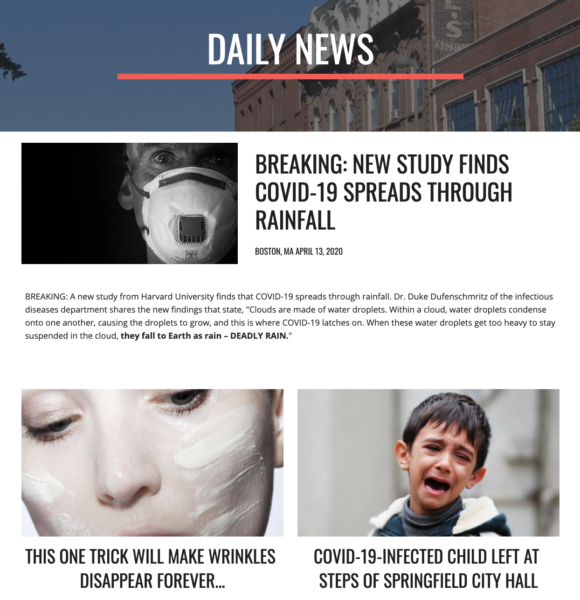

I decided to approach the lesson from another perspective. We need to be bullshit detectors, I thought. So let’s make some bullshit. I asked students what an article needed for them to believe it. We agreed it had to be at least a little credible. A mainstream fake news article with aliens or bat boys found in caves wouldn’t cut it. But the common thread in our discussion was that to be believable, a headline needs to hit you emotionally – whether the emotion is fear, anger, pride, or disgust. Once you feel it, your critical thinking skills can fade to the background. Throw in an alarming image, a made-up medical study and a disturbing quote from a reliable-sounding source, and there you have it. As we talked, I shared my screen, creating a new website from scratch. I named it the Holyoke Daily News, and as the top headline we landed on, “Breaking: New study finds Covid-19 spreads through rainfall.” Outside it was drizzling.

To round out our front page we added a classic “This new trick…” ad for miracle cream and a heartstring-pulling headline about a coronavirus-infected child left on the steps of city hall.

The whole thing was done in less than 10 minutes. It certainly wasn’t perfect, but it was enough. Some students were surprised that the big bad machines behind fake news might just be bored, apathetic people who wanted to get a little attention or make some money. It was just someone lying to you to get shares and page views? (Or to destroy elections. Or lives.)

In early May, a student reached out to me and my colleagues by email. She had just watched the newly posted #Plandemic video and was disturbed. “Is this real media or not?” she asked us. Not soon after, my phone buzzed with an alert from the New York Times: Twitter and Facebook were working to remove the viral conspiracy theory video from their platforms. I was so proud of her. She had noticed how the video had made her feel: angry and sick. And that made her wonder – am I being manipulated? Something doesn’t feel right. Believing is too easy: the dolphins are Photoshopped.

Ann Ward is the Program Director at Bard Microcollege Holyoke. A transplant from Montreal, Ann has an MFA in Creative Writing from UMass Amherst and lives in Western Massachusetts. You can find more of her work at annward.ca.

For more on the Bard Microcolleges, go here.