Buenos Aires, Argentina – It’s nearly lunchtime, and a buzz of activity fills the wide central corridor of Centro Universitario San Martin (CUSAM), a university in the state of Buenos Aires.

People stream in and out of classrooms. Some students rush off to grab a quick meal. Others gather in the director’s office to debate the state of Argentina’s education system.

Were it not for the tall fences topped with razor wire or the multiple security checkpoints, CUSAM might seem like any other higher-education facility.

But CUSAM is situated in the San Martin prison, a maximum-security facility located about an hour from Argentina’s capital city.

There, imprisoned men and women — as well as prison staff — attend in-person classes affiliated with the National University of San Martin, a public university based nearby. They can even earn degrees in sociology and social work.

“This is like any other university. It just happens to be in a prison,” said Matias Bruno, a professor from the National University who works at CUSAM.

But as Argentina’s prison population continues to grow and investment in public education wavers, experts like Bruno fear fewer and fewer resources may be devoted to education behind bars.

That fear has mushroomed in the months since libertarian President Javier Milei took office in December. As part of his cost-cutting agenda, Milei has floated the idea of privatising the country’s prison system and building new facilities to house up to 6,000 people at a time.

Still, one man’s success story has come to symbolise the potential of prison education programmes like CUSAM.

After all, he did not just benefit from the programme. He helped to found it.

Waldemar Cubilla was only 14 years old when he was first arrested.

Born in La Carcova, an informal settlement built next to the largest open-air dump in the country, Cubilla grew up during one of Argentina’s worst economic crises.

It was the late 1990s, and the country had plunged into a deep economic depression. Over the span of four years, its economy contracted by nearly 28 percent. Factories shuttered. Bank accounts were frozen. And some residents took to looting grocery stores to satisfy their hunger.

Like many people in La Carcova, Cubilla survived by digging through the rubbish to find food or items to sell. But he eventually turned to theft, along with other teens in the neighbourhood.

All the while, though, Cubilla continued attending school, finding solace in learning.

“He always loved books,” said Gisela Perez, his partner and the mother of his two children. She and Cubilla met as teenagers. “He knew that studying was the way to change his life, but things were tough, and he got involved in crime. In his backpack, he used to carry a gun and a book.”

By the time he was 23, Cubilla had been arrested twice on armed robbery charges. The first time, when he was 14 years old, cost him a month in a juvenile facility.

The second time, however, he spent five years in a maximum-security prison.

“The prison had a small room where people who wanted to study law could access the reading material and then sit the exams,” Cubilla explained.

As he finished his high school diploma behind bars, he convinced the prison director to allow him to study law too.

“There, we had no teachers, but it was something,” Cubilla said. “I was finishing school in the morning, and in the afternoon, I was allowed to access the law books.”

He smiled at the memory. “It was a good deal because I was learning and could spend time outside of my cell.”

When he was released in 2005, Cubilla enrolled in a private university to complete his law degree. But money was tight, and he went back to what he knew: robbing cars to support his family and pay the university fees.

“It was strange living in those two worlds: the world of crime and also being a university student,” he recalled.

That double life, however, would not last long.

The third time he was arrested, Cubilla was sent to a new prison close to his home.

It was called Unit 48 of San Martin, and it had been set up in a building that had been long abandoned.

In his mid-20s at the time — an energetic man with a muscular build and short dark hair — Cubilla still had his zest for learning. His family would sometimes drop by with books or magazines for him to read.

But as he settled in the San Martin prison, Cubilla ran into other imprisoned men he knew — and he discovered that they too wanted to study.

But some of the men lacked basic education skills. “There were many people who couldn’t read or write,” Cubilla recalled.

He noticed that their lack of literacy even hindered them in court. “They would receive documentation about their legal cases and could not understand what was written, so it was important to do something about that.”

Cubilla gathered his books and decided to teach some of the men to read. They asked the prison director to allow them to open a small library.

“Originally, the idea was to have a library, just a space to read and learn,” Cubilla said. “Then we realised we could do more.”

What inspired Cubilla was a tradition of free university programmes, housed in Argentina’s prisons.

Like other countries — particularly in Europe and North America — Argentina started to introduce higher-level learning behind bars during the 20th century.

Its first university programme was founded in 1985, as the country emerged from a period of dictatorship.

Since then, access to education has grown. A study in 2022 found that 17 out of Argentina’s 24 jurisdictions had collaborations between certain prison facilities and public universities.

But just as the education programmes were flourishing, so too was the need.

According to the most recent government data, the nationwide prison population reached a record of 105,053 people in 2022.

That marks a 233 percent increase over the number of imprisoned people in 2002, just two decades prior.

Overcrowding in Argentina’s prisons is common. So too are sparse conditions: Some lack basic sanitary supplies, healthcare services and even beds.

Unsurprisingly, the number of imprisoned people accessing higher-level education is also relatively low.

As of 2022, approximately 5.5 percent of women and 4.5 percent of men reported participating in university-level education programmes. The majority participated in no educational enrichment at all.

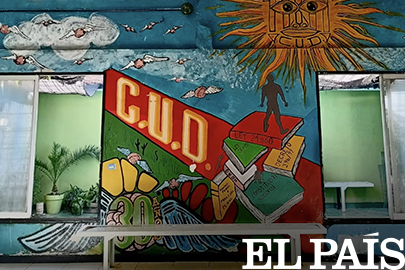

But when Cubilla started to organise CUSAM, San Martin’s in-prison university, he saw an opportunity not only to improve his cellmates’ lives — but also the prison itself.

“This is about a lot more than studying,” Cubilla said. “I remember that, when I got to leave my cell, I would take the chance to talk to other prisoners, see what they needed. Talking about the university was an excuse to foster better relations between people in the prison, and it contributed to a reduction in violence.”

He and other men at the San Martin prison reached out to the National University of San Martin for help in setting up CUSAM.

Bruno, one of the professors who took part in the exchange, explained that they decided to offer degrees in sociology and social work precisely because those subject matters taught students to approach conflict in a different way.

“People here are not prisoners but students,” Bruno said of CUSAM’s philosophy. “The idea is that, through learning, we can help them develop critical thinking and become responsible citizens.”

Studies have also shown that education helps reduce the risk of recidivism.

The University of Buenos Aires, for example, found that 84 percent of the people who graduated from a prison education programme in 2013 did not reoffend in the years immediately afterwards.

That trend has also been documented in the United States, one of the countries with the highest incarceration rates in the world.

A 2021 study from the Bard Prison Initiative and Yale University found that the more college credits an imprisoned person earned, the lower their recidivism rate was likely to be.

For students who earned a bachelor’s degree, for instance, the recidivism rate fell to 3.1 percent — far below the national rate of nearly 60 percent.

“A university education has the power to change the trajectory of the lives of imprisoned students, not just because they are far less likely to ever go back to prison, but also because education opens worlds of opportunity and possibility,” Jessica Neptune, the director of national engagement at the Bard Prison Initiative, told Al Jazeera.

Since CUSAM was founded in 2008, Bruno estimates that at least 1,000 students have benefitted from its resources and classes. Sixteen of its students have even graduated with university degrees.

But austerity measures put in place under President Milei have led to concern for CUSAM’s future.

Bruno and several other instructors who spoke to Al Jazeera said CUSAM’s professors are struggling with salaries that have not grown to match Argentina’s triple-digit inflation.

Budget cuts are also affecting the availability of reading materials. Students now either share texts or wait to consult copies of the books they need in the library. But professors like Bruno warn that the shortages are making learning in the prison even harder.

As Milei slashes government spending in an effort to rein in the national debt, critics fear the long-term repercussions of cuts to social programmes and public education.

They also worry how Milei’s plans might reshape the prison system. In an interview with CNN, the president expressed interest in selling the land some public prisons sit on as valuable urban real estate.

One of the sites believed to be under consideration is the Devoto penitentiary, the site of Argentina’s first in-prison university programmes.

Milei also told CNN he plans to build what critics call mega-prisons.

“We are thinking of building some prisons with 5,000 or 6,000 spaces,” the president said. The real estate sales, he added, will help finance their construction away from urban centres.

“And then we arrive at a prison with better security, better quality, better services, larger. And all without spending a single peso.”

But Bruno, the professor working with CUSAM, believes “education is the best security policy” because it gives people the tools they need so they stay away from crime.

“People have this fantasy that — when someone is released from prison after, say, 15 years of living in terrible conditions and has a criminal record for another 10 years — still they will somehow be able to find a nicely paid office job in a nice part of town in some multinational company,” he said.

“That’s just not what happens. In CUSAM, we are proposing a different approach.”

Even for Cubilla, the transition back to life outside of prison was difficult.

Behind bars, he graduated from the sociology programme with one of the best overall scores of any student — either in or out of prison — that year, according to CUSAM’s professors. He has since become a sociology professor himself, returning to CUSAM to teach.

But Cubilla himself was released from prison in 2011. After years of incarceration, it was difficult to adapt to life back in his hometown of La Carcova.

“Life had changed for most of us. We had new jobs that were keeping us busy and raising kids,” Perez, his partner, explained. “It was hard for Waldemar to find a new space, a new role among all of that.”

Inspiration came from a familiar source, though. Cubilla remembers a friend approached him with an idea: “You like books. Why don’t you open a library here?”

So he took the experience he gained founding CUSAM and applied it to building a community library for his neighbourhood.

“In the beginning, people thought we were crazy, but I knew that the library was a good idea. It had worked in the prison, and it was going to work here,” he said.

Now, a building with three rooms rises from a part of the neighbourhood where there was once only rubbish. The library sits next to an outdoor shrine to Gauchito Gil, an Argentinian folk hero who used to take from the rich to give to the poor.

Cubilla and Perez estimate that 30 local children stay in the library each day while their parents work. They see the library — just like CUSAM — as a ladder to help people reach a better life.

Cubilla has also recently become an international fellow with the Incarceration Nations Network, a global initiative to promote high-level education for people in prisons across the world.

“Things are difficult, but we have come a very long way. Many of the projects we’ve done so far were based on pure intuition, but now, we have experience,” Cubilla said.

“We know education is the best strategy. We know that education works.”

Josefina is the 2024 BPI Global Research Fellow. In her role, she will spend her fellowship writing and publishing about budding and existing higher education initiatives in prisons across Latin America and elsewhere around the world.