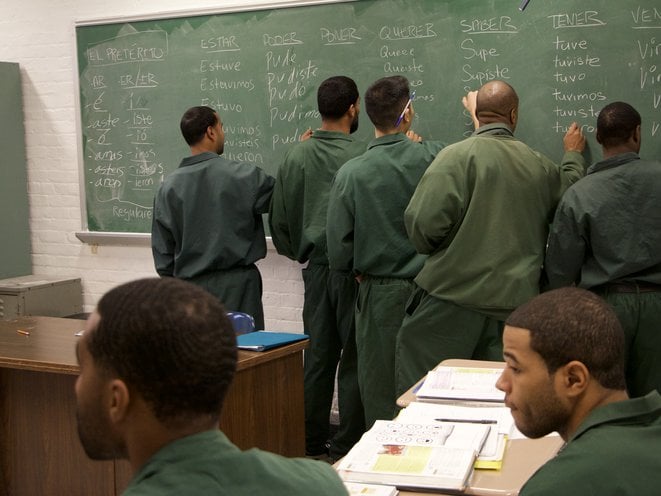

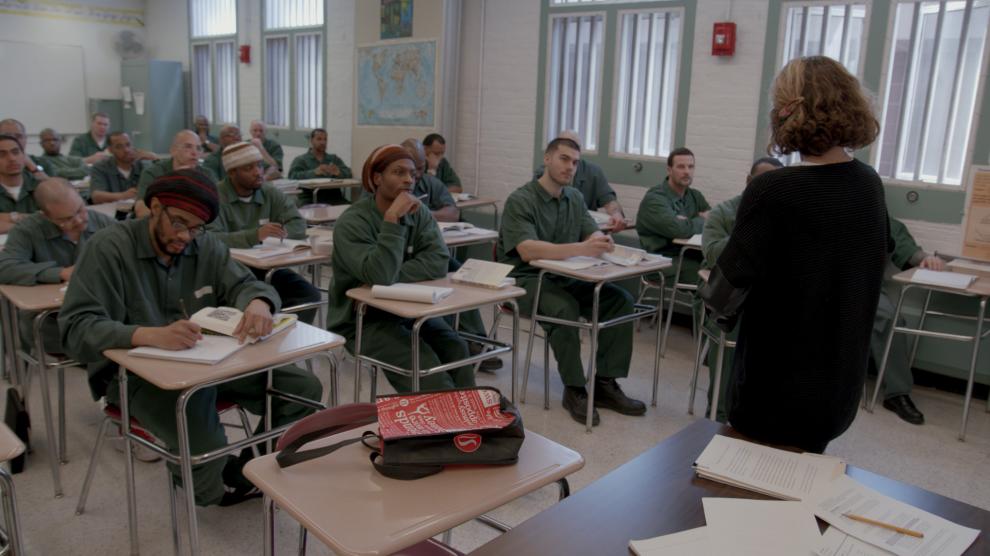

Bard Prison Initiative (BPI) students conjugate Spanish verbs at Eastern New York Correctional Facility. SKIFF MOUNTAIN FILMS

By Lynn Novick

Special to The Times

In February 2012, my longtime producer and collaborator, Sarah Botstein, and I were invited to give a guest lecture and show scenes from our documentary, “Prohibition,” to college students taking a course on the history of social movements in America. We had been promoting the film for months, but this was something new — these students were earning their degrees inside Eastern NY Correctional Facility, a maximum-security prison in Napanoch, New York. Not only were the incarcerated students thoughtful, sophisticated and knowledgeable, they asked the most insightful and probing questions we had ever been asked. It was a profound and unforgettable experience, and it upended every preconception I had about the people who are behind bars in America.

I have been a documentary filmmaker and student of history for 30 years and consider myself a reasonably well-informed, socially conscious person. But before that night, everything I knew, and assumed, about prisons and about the men and women incarcerated in them I had learned from newspapers, magazines, radio, books, movies and television. Mass incarceration — and its catastrophic disproportional impact on African Americans and people of color — for me was an abstraction until I walked into Eastern that night. While nearly every person of color I know has firsthand knowledge of incarceration, I did not know anyone who had served time in prison or had been convicted of a serious crime. To quote the inestimable lawyer and social-justice activist Bryan Stevenson, I did not have proximity to the problem.

Nor, I am ashamed to say, did I fully appreciate how thoroughly and tragically the tyranny of low expectations has infected our public-education system over generations. Most of the men and women who end up in prison in my home state come from the poorest neighborhoods in New York City and attended overcrowded, segregated, underresourced public schools. The Bronx Defenders’ Chief of Staff, Wesley Caines, who grew up in the Bronx and was incarcerated for 25 years, realized only after studying with college professors in prison that he had been cheated by his New York City education, which had not been nearly challenging enough. “There is a dual educational system in this country,” Caines says, “one for individuals who will rule and one for everyone else. What are the ramifications for American society,” when so many of our fellow citizens are being denied the opportunity to realize their potential?

Systematically and unjustly denied access to educational opportunity in their communities, the vast majority of people who end up in the prison system have no access to higher education behind bars, either. Corrections departments are supposed to rehabilitate people, to prepare them for returning to society, but with recidivism rates of 50-60%, clearly the opposite is true.

But it was not always this way. Higher education in prison was commonplace in America until 1994, when the Clinton Crime Bill banned federal Pell Grants for people in prison. Overnight, college behind bars was decimated. Privately funded programs like the one we visited, the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI), slowly sprang up, but they do not begin to fill the enormous need. New York, it turns out, does more than most, but of the state’s more than 50,000 incarcerated men and women, only 950 are enrolled in college programs. Three-hundred of them are in BPI, working toward AA and BA degrees from Bard College, and they are held to exactly the same high academic standards as students on the college’s main campus. Max Kenner, the program’s executive director, says, “BPI is a very simple kind of experiment, which is what happens when we provide the kind of education that typically in the United States is only afforded to the children of the lucky or the entitled or the rich to others.”

With Congress considering bipartisan legislation this fall to reinstate Pell eligibility for incarcerated men and women, access to higher education behind bars may expand exponentially across the country, which has the potential to significantly reshape the criminal justice system. Those who have access to higher education while incarcerated, studies have shown, return to prison at dramatically lower rates. Of the 600 BPI alumni who have been released in the past 20 years, only 4% have gone back to prison.

To document for a larger public how and why education is so transformative we filmed a small group of men and women over a four-year period as they tried to earn degrees while behind bars. Being present as these men and women experienced the enormous power of education was life-altering for me in ways I never could have anticipated. Their stories, their lived experiences, revealed many dimensions of the grievous intersections of race, class, poverty and criminal justice in America, but they also taught me a great deal about resilience, determination and the joy of learning.

Bard Prison Initiative students at Eastern New York Correctional Facility in an advanced bachelor’s degree seminar. (Courtesy of Skiff Mountain Films)

Tamika Graham, whose mother was raising her teenage daughter while she served an eight year sentence, resolved to earn her AA degree while incarcerated to set a positive example. “I want my daughter to see that if I can do this in here,” she said, “there’s no reason why she can’t do it out there.” Dyjuan Tatro, who grew up in poverty, dropped out of high school and was incarcerated as a teenager, never imagined himself going to college. After six years in prison, he enrolled in BPI and for the first time in his life completely dedicated himself to education. “This is not just getting a degree,” he said. “It’s changing fundamentally the way I think, the way I interact with people.” Outside the classroom, Dyjuan discovered a passion for debate and participated in BPI’s historic win over Harvard, which made headlines around the world.

Many of the students we got to know — like nearly half of the 2.2 million men and women behind bars in America — are not the “nonviolent drug offenders” we hear so much about in criminal justice reform debates. They were convicted of serious, violent crimes, and their stories give lie to the prevailing assumption that people who have done harm cannot change. Going to college in prison and engaging the rigorous liberal arts curriculum prompted “a maturing of the soul,” Sebastian Yoon said. “Compared to four years ago, we’re not the same people we were.” The students developed the tools to understand, contextualize, take responsibility for and, going forward, to make up for their actions. A few days before his release (after 12 years), Giovannie Hernandez reflected, “I want my life to be a testament to the person’s life I took. That requires working to the best of my ability in making my life itself a symbolic memorial to his. If I don’t, I’m further disrespecting his memory. That’s the only way I’ll be able to redeem myself.”

Recently, Jule Hall (he earned his BA in prison in 2011 and is now a program associate at the Ford Foundation) and Bronx Defenders’ Caines returned to Eastern to meet with incarcerated students there. “You’re going through a process of re-entry right now that will prepare you for similar, if not even harder, challenges,” Hall told them. “But you’ll be prepared to take them on because you’re fully engaged in this program right now.” “Everything I do every day,” Caines added, “is in recognition of the 25 years I spent incarcerated, and the fact that across this country, there are still people in cages. I love this program. It allowed for me to find life and to grow, and to progress while in my cage.”

Lynn Novick is an Emmy, Peabody and Alfred I. duPont Columbia Award-winning documentary filmmaker. For nearly 30 years, she has been producing and directing documentaries about American culture, history, politics, sports, art and music. In collaboration with co-director Ken Burns, she has created more than 80 hours of acclaimed programming for PBS, including “The Vietnam War,” “Baseball,” “Jazz,” “Frank Lloyd Wright,” “The War” and “Prohibition.”