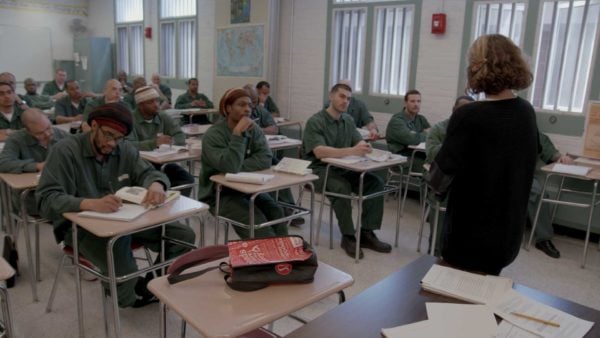

Bard Prison Initiative (BPI) students at Eastern New York Correctional Facility in an advanced bachelor’s degree seminar. (Courtesy of Skiff Mountain Films)

“Inside the walls of a classroom, you escape the walls of a cell — and you become an individual again.” So says Shawnta Montgomery, speaking at her graduation in the Bard Prison Initiative in College Behind Bars, the latest documentary project from Ken Burns and Lynn Novick.

The four-part series follows men and women incarcerated in maximum and medium security prisons across New York state over the span of four years, as they attempt to gain college degrees through the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI), one of the most rigorous prison education programs in the U.S.

BPI operates out of six New York State prisons. Students undergo a rigorous admissions process and then enroll full-time into the same classes they would take on Bard College’s main campus. They’re taught by college faculty in seminar settings, and held to the same academic standard as any other Bard student. BPI issues associate degrees and bachelor’s degrees.

BPI was founded in 1999, five years after Congress ended inmates’ eligibility for federal Pell grants (need-based grants from the U.S. government to help students with financial need pay for college) as part of the Clinton Crime Bill, during the era of “tough on crime” policies. While some colleges decided to continue to grant degrees to prisons, operating off of private donations, at the time only three other programs in N.Y. state extended higher education to inmates. Dozens of other colleges now operate in prisons across the U.S.

In 2016, the Obama administration started a pilot program to offer some Pell grants to incarcerated Americans again; in June Education Secretary Betsy DeVos called on making the program permanent. (Eighty six percent of BPI is privately funded by donations and private grants, but 14% comes from public funding.)

But the pilot program only extended eligibility to some 12,000 inmates, out of the over 2 million incarcerated people in the U.S. College Behind Bars makes a moral and fiscal case to change that. The filmmakers aren’t alone in this opinion; criminal justice reform has become an increasingly nonpartisan issue over the past few years. A 2016 study by the nonpartisan think tank the RAND Corporation found that inmates who participated in educational programs were up to 43% less likely to reoffend and return to prison. That same study found that for every dollar invested into correctional education, nearly five dollars is saved in reincarceration costs over three years.

Executive produced by Burns and directed by Novick in her solo directorial debut, College Behind Bars was also produced by their longtime collaborator Sarah Botstein and edited by Tricia Reidy.

To discuss the project, TIME sat down with Novick, Botstein, and Dyjuan Tatro, one of the incarcerated BPI students who appears in the film. Tatro was released from prison in 2017.

TIME: Dyjuan, what was it like being part of this documentary?

Dyjuan Tatro: It has been a really great experience. Lynn and Sarah have been really respectful to us. When they first showed up, there was some skepticism because of the type of stories that are conventionally told about incarcerated people in this country. But those of us in the BPI community sat down and looked at their body of work, at how rigorous it is, how they always look at both sides of an issue. We decided they were people that we could trust.

Typically, you would know when people are coming to film you. But we were in prison and couldn’t have [outside] contact with Lynn and Sarah. They would just show up and be there with the cameras, and you’d never really get used to that. But they made a big effort, again, to be respectful. If you watch the film, there’s no narrator. It’s us telling our stories. They really brought our voices through and made a film that changes the narrative around who incarcerated people are and what we’re capable of.

Director Lynn Novick and cinematographer Buddy Squires on location at Eastern New York Correctional Facility. Skiff Mountain Films

Lynn and Sarah, you were granted extensive access to shoot this documentary. How did that come about? And what was that experience like for you both, on the other side of the camera?

Sarah Botstein: The Department of Corrections and Acting Commissioner Anthony Annucci are really supportive of what New York state is doing in higher education; Bard is really a program they’re enormously proud of and have been supportive of for over a decade.

We were joking about this last night: I think when they initially gave us ‘unprecedented access,’ they didn’t quite know what they were getting into. They kept saying that they thought we’d come a few times a year and just be on the school floor… I think they didn’t quite realize that we would want to go and do research, spend time with the students, and time in the classrooms. We were a small, lean, efficient crew and we feel really fortunate that they gave us the access that they did, because it makes the film what it is.

Neither of us had been inside a prison before. It’s a very serious place to be. It felt really important and urgent. We were very privileged to be there in the way that we were.

Lynn Novick: One of the things we talked about a lot with our team was, if you film just the students in class, you don’t realize where they are. When we had screenings of some of the raw materials, colleagues would say, ‘wait, you have to show the audience that they’re actually doing this incredible academic work inside the context of prison.’ So we kept having to ask, ‘now we want to see the yard, we want to see people in their cells, we want to see what it’s like to walk down the hall.’

Reporters have often faced critiques of working as ‘parachute journalists,’ able to enter a space or environment and then leave while the subjects cannot. Was that something you had to reckon with?

Novick: We hope that we did not function like parachute journalists. When [Sarah and I] were working on The Vietnam War, we’d see correspondents just show up with their camera… and bring footage back home without really having much contact with what was actually happening. That’s my image of a parachute journalist. I think we tried to be the opposite, as much as possible, within the constraints that we had.

Tatro: Lynn and Sarah were there to shoot and make a film, but they were also there to learn about us in the program. As Sarah said, they spent just as much time with us in prison without cameras as they did with them. We’ve had conversations about all types of things and spent a lot of time with them, and have gotten to know them and their families. I spent my first Thanksgiving out of prison at Lynn Novick’s house. A real, deep relationship has developed during the course of this project.

Cinematographer Nadia Hallgren on location at Eastern New York Correctional Facility. Skiff Mountain Films

Over the course of filming, criminal justice reform has become an increasingly urgent issue in the U.S. How did that impact the project?

Novick: In the past few years there’ve been deeper conversations about social justice and injustice generally, and I think at the beginning of this project it didn’t feel like education was in the middle of those conversations. Now it really is.

Botstein: When we started preparing, PBS would ask us what we were working on, and we’d say, ‘We want to make this film about an amazing college prison program.’ And people were like, ‘Okay, that’s interesting.’

By the time we started shooting in 2014 [and in the years since]… the conversation around criminal justice reform, and where higher education sits in that conversation, became more and more dynamic. It was unfolding in real-time — the personal transformative education that students were getting; the politics were changing so quickly. It became a very different story.

Tatro: You see it in the film. Politics becomes a character, [becomes] a bit of a motif… and how it changes throughout is really interesting to watch.

Dyjuan, the documentary explores the fact that both you and your brother have been incarcerated. You were able to obtain a degree while your brother was not, because BPI does not operate out of the prison where he was held. How has it been for each of you maneuvering life after incarceration, you with a degree and him without one?

Tatro: The difference is very stark to me. I actually have two brothers, one older and one younger. They’ve both been incarcerated. And when I look at the types of things that have been available to me coming out of prison versus the opportunities that they’ve had without a college degree, and more importantly, without a college education — that drives my work every day. I’m [now] the government affairs officer at the Bard Prison Initiative. I’m back with BPI working to expand access to college in prison for currently incarcerated men and women, and I’m working specifically right now on attaining public funding for the work that we do.

If we’re going to meet the problem at scale, we need public funding in this space — so men like my brothers can have access to the same opportunities that I had, because it was life changing.

The documentary includes critical discussion of BPI; specifically, one student’s mother objects to the fact that her incarcerated child gets a free education while she has to pay to educate her siblings. What do you make of that criticism?

Tatro: I think it’s a really important scene. One of the things it highlights for me is just how powerful the rhetoric [that we shouldn’t support college in prison] has been. We need to be thinking about how we want people to come back into society. Ninety five percent of people in prison are going to be released; how do we want them returning back to their communities?

College in prison is cost-effective, so this is not really a concern about taxpayer money. It’s really a question of punishing people, right? Prison in this society functions to punish people. So if we want prison to be a reformative space, we have to give people access to education. BPI’s argument is for college in general, not in particular. This is a program that highlights how important college and the educational experience is to everyone in this country.

Botstein: We tend to marry the question of the cost of higher education and education in prison, and those things are separate. The rising cost of education shouldn’t actually directly factor into how you feel about the cost of educating people who are incarcerated.

Novick: And I think there’s one more layer that we don’t always focus on: educational equity in our society does not exist. The vast majority of people who are incarcerated have not had access to education before being incarcerated. And that may be partly how they ended up being incarcerated. Where do we sit as a society in terms of the American dream and equal opportunity?

Producer Sarah Botstein and cinematographer Buddy Squires on location at Taconic Correctional Facility. Skiff Mountain Films

Lynn and Sarah, what do you want viewers to take away from your documentary?

Botstein: We always say we hope the film will raise two really important questions: who in our country should, and does have access to education? And what is prison for? We hope people think about how those two questions intersect with the systemic issues of race and poverty, and what is broken about our country.

I will also say, one of the things, at least on the filmmaking side, that we couldn’t have told you six years ago is that in the sea of really dark hard problems that our country faces, this is the story of hope, and energy and a little bit of brightness. I don’t want to sugarcoat it, but I think it’s a solvable problem. We want our viewers to think about how they can help solve it.

And Dyjuan, as someone in the documentary, what do you want viewers to take away?

Tatro: I want people to acknowledge the amount of humanity and potential that we have locked away in this country, and think about the ways in which we can make a more inclusive society for us all.

The second part of College Behind Bars airs tonight, Nov. 26, at 9 p.m. EST. and is available to stream at PBS.org.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.