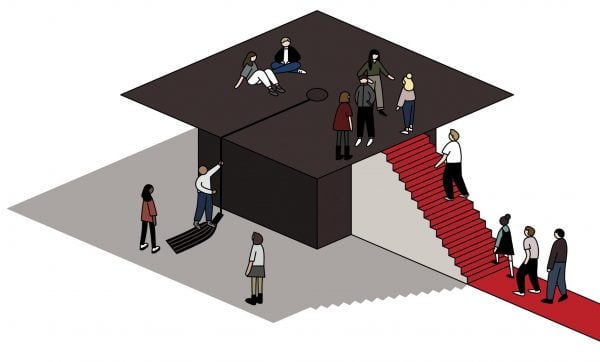

This time of year, there’s a lot of optimism in the air about college. As acceptance notices come in, it seems like the smartest, hardest-working young people with the greatest potential are being matched to institutions of higher learning that will prepare them for success and promote a free and open society. We might conclude that colleges are greasing the gears of social mobility, which have slowed as of late.

It’s painful to think otherwise, especially for someone like me for whom access to a selective college was a boon and a blessing. The son of a hardware store owner, I attended New York City public schools and got both an undergraduate and a law degree from Cornell. With the support of my loving family, I prospered. In 2000, I was appointed chancellor of the New York City public schools; after that I made investments in classroom technology before being tapped to run a foundation that paves the way for high-performing, low-income students to attend college.

Last year, though, the good luck that has characterized my life ran out. My doctor informed me that I am dying of A.L.S. In my remaining days, I feel a great urgency to speak boldly about a troubling fact: Despite the best efforts of many, the gap between the numbers of rich and poor college graduates continues to grow.

It’s true that access programs take some academically talented children from poor and working-poor families to selective colleges, but that pipeline remains frustratingly narrow. And some colleges and universities have adopted aggressive policies to create economic diversity on campus. But others are lagging. Too many academically talented children who come from families where household income hovers at the American median of $59,000 or below are shut out of college or shunted away from selective universities.