I have never felt utter despair and failure more than when I began my incarceration. That was the most difficult, seemingly hopeless point of my life—rock bottom, so to speak. I ultimately served a decade in prison.

My life took yet another unexpected turn from despair to hope when I gained acceptance to a widely acclaimed college-in-prison program—the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI). From that point onward, I began to perceive the dismal circumstances I faced in a vastly new light, one beaming with the prospects of learning and opportunity.

With the return of public funding for college in prison in New York State putting an end to the 26-year ban on Tuition Assistance Program (TAP) grants, thousands more people incarcerated in New York prisons may have the opportunity to experience the same journey from despair and failure to hope and opportunity. My story shows how that’s possible. In New York alone, over 700 incarcerated students have earned college degrees through BPI.

In a preliminary course that preceded my first semester with BPI, my class was assigned Martin Luther King Jr’s “Letter From a Birmingham Jail.” I recall how inspired I was by Dr. King, by his perseverance and resilience. I was inspired that, despite his own imprisonment coupled by the reluctance of his fellow colleagues and clergy members to garner support for him at a time of utmost need, King remained committed to his pursuit of human equality and civil rights; and indeed, he had sacrificed his own freedom for the rights of so many others, perhaps even for the sake of freedom itself.

In retrospect, it is clear to see why my enrollment with BPI was such a pivotal moment during my incarceration. In the spirit of Dr. King, I looked to education to transcend the prison walls that had confined me, as well as for a purpose that could redefine who I had become. By creating access to college education while in prison, BPI empowered me to work toward something advantageous for my future and afforded me an opportunity to pursue something truly positive in spite of the negative circumstance of my confinement.

When I graduated in prison in 2019 at the age of 36, I proudly became the first person in my family to earn a college degree. It was a monumental achievement for everyone–my advisors and professors, my colleagues and friends–and especially, for my family and me.

My experience with BPI has been life-changing, to say the least. In fact, I would describe my journey with BPI as nothing less than eye-opening and thought-provoking. My ability to convey ideas and thoughts clearly and comprehensively, as well as my aptitude for literacy and competency, have significantly improved. Furthermore, BPI challenged me to be a critical thinker, to be open-minded, as well as to engage in intellectual discussions while sharing spaces that nurture and maintain values such as dignity and respect towards all.

Now that New York State has repealed the ban on TAP, and invested in making college accessible in prison, the state stands to save itself upwards of between $22 to $27.5 million in costs we currently use to keep people incarcerated.

According to a recent study published by the Yale Policy Lab measuring the impact of college-in-prison on recidivism rates in New York, BPI students who earned an associate degree during their incarceration showed an 8.2 % rate of recidivism, a stark contrast to the general rate of 41.5%. (1) The results of this study obviously hit close to home; from my standpoint, it offers a compelling explanation as to how and why I have been able to break the vicious cycle of incarceration: because simply earning an education while in prison significantly reduced the likelihood that I would return to prison. How so?

It is no secret that the overwhelming majority of jobs and professions in the labor market minimally require some form of education, which certainly speaks to the pragmatic value of having one. And so, especially for those individuals who have criminal convictions, the ability to access education during one’s incarceration is arguably the most important and beneficial avenue that can be made available to incarcerated people, adding incentive for potential employers who might not otherwise consider someone with a criminal record.

I strongly believe that education is fundamental to everyone’s personal and social development, possessing the capacity to provide individuals with the kinds of skill sets that are not only marketable but moreover, requisite in order to join the labor market and become productive members of society who contribute in thoughtful and meaningful ways.

But for incarcerated people who must struggle to stay afloat while transitioning back into society once they are released, educational attainment serves as a lifeline for those hoping to secure gainful employment and maintain a stable living. After all, both education and gainful employment ultimately work in conjunction to establish a safety net for all individuals and their loved ones, and thereby, are of utmost importance in ensuring a chance to pursue a long and successful life.

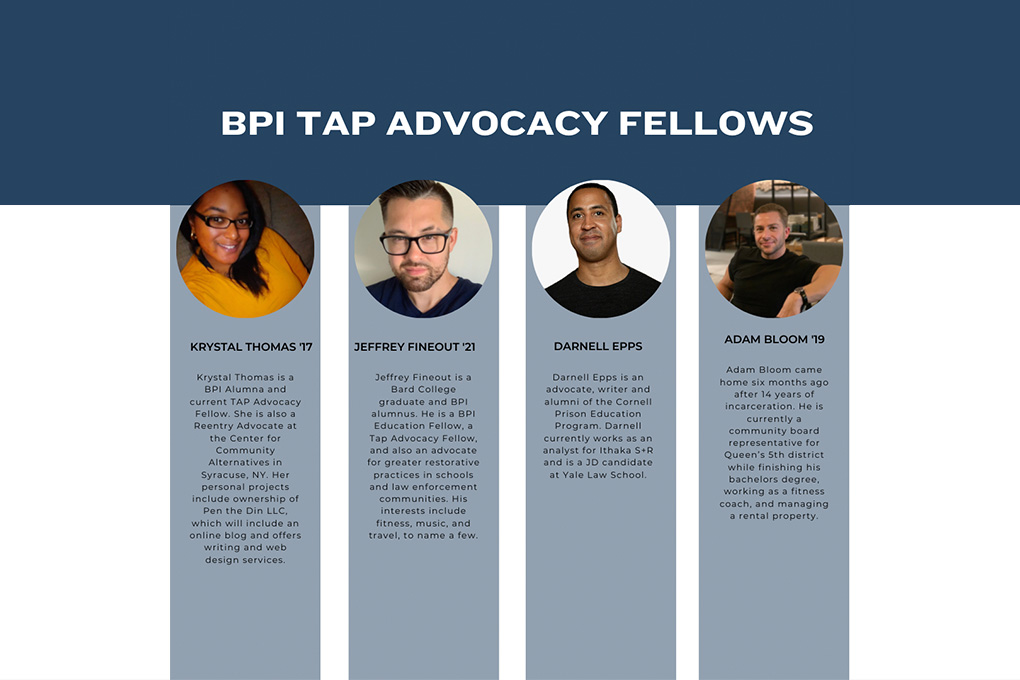

Jeffrey Fineout ’21 is a Bard College graduate and BPI alumnus. He is an advocate for greater restorative practices in schools and law enforcement communities. His interests include fitness, music, and travel, to name a few.

Jeffrey Fineout ’21 is a Bard College graduate and BPI alumnus. He is an advocate for greater restorative practices in schools and law enforcement communities. His interests include fitness, music, and travel, to name a few.

(1) Matthew G.T. Denney & Robert Tynes (2021), “The Effects of College in Prison and Policy Implications,” Justice Quarterly, 38:7, 1542-1566, https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2021.2005122.