At a recent orientation session for newly enrolled Bard students at Taconic Correctional Facility, I found myself thinking about my own undergraduate experience and the ways Bard connects people across campuses and decades. We were there to talk about the extended world of the College—the Bard archipelago stretching from Al-Quds to Baltimore to Kyrgyzstan—and also to explain what it means to be a Bard student at that particular campus.

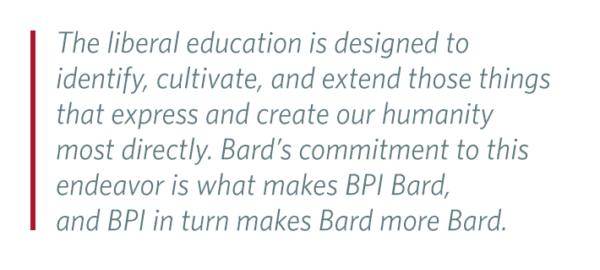

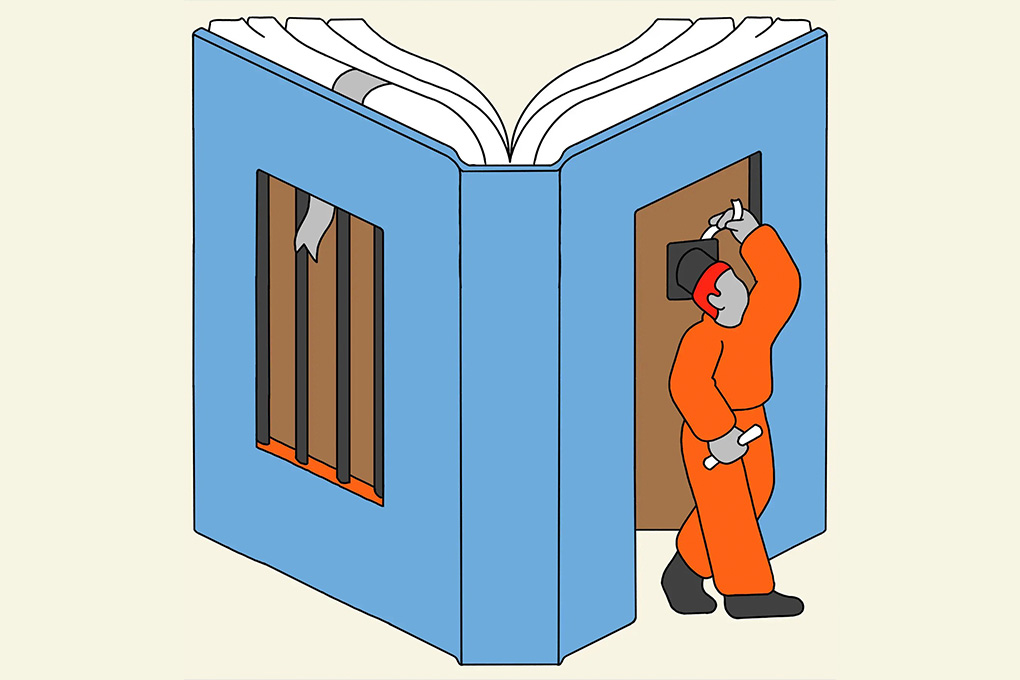

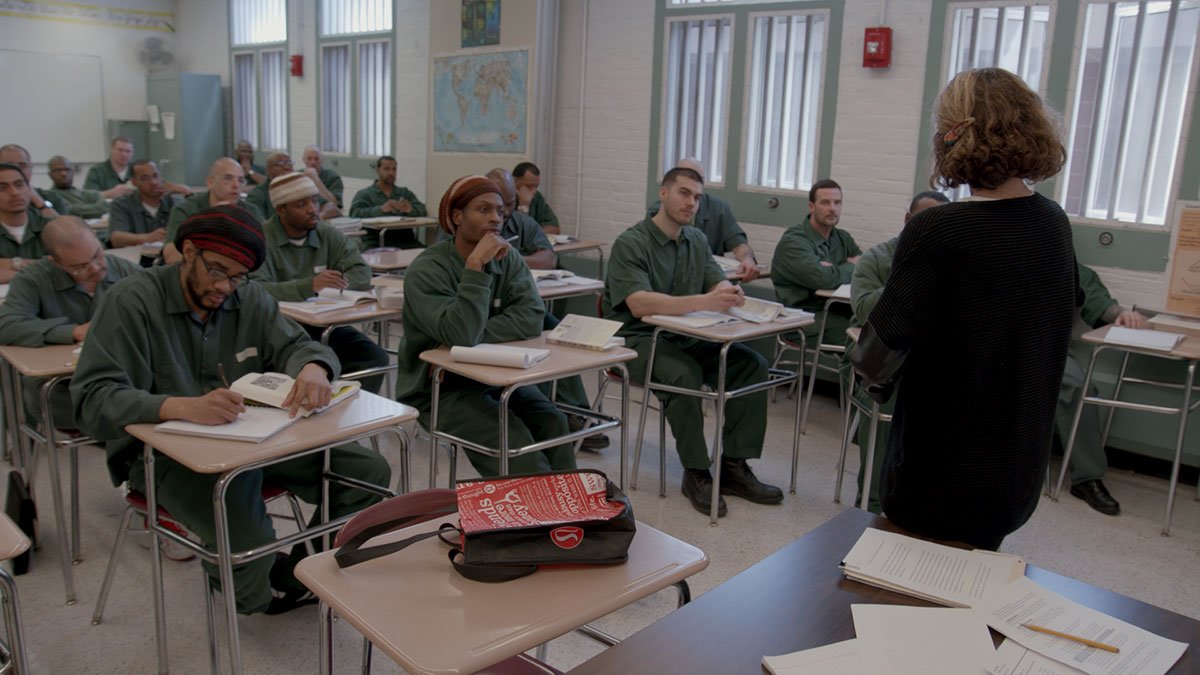

Bard Prison Initiative (BPI) students at Eastern New York Correctional Facility in an advanced bachelor’s degree seminar. (Skiff Mountain Films)

Orientations focus on the mutual commitment between the College and its students and alumni. Once you accept the invitation to enroll, we are with you for life. We speak frankly and seriously about the mutual promise that enrollment entails. For the student, the obligation is to prioritize coursework and to be selfish; to guard your time and allow yourself to focus deeply on school. For the College, the commitment is to make stringent demands on you and to equip you to meet those demands. The College promises to see you, and to see you through.

From its inception, the Bard Prison Initiative (BPI) has been a quintessentially Bard endeavor. Max Kenner ’01 launched BPI as a sophomore in 1999. Having recognized the pressing need to restore college opportunity for incarcerated people a few years after the 1994 “crime bill” made them ineligible for Pell Grants, he met with President Leon Botstein and other College leaders to sketch a vision, and then set out to find a prison that would welcome Bard. He drove hundreds of miles across New York State, meeting with prison officials and educators to determine where and how best to approach the project. He finally landed at Eastern NY Correctional Facility, in Napanoch, a little under an hour from Annandale. Now, 20 years later, with more than 100 students enrolled at any given time, the BPI site at Eastern is the largest of six Bard College campuses inside prisons around the Hudson Valley. Bard students at those campuses earn associate and bachelor’s degrees. They begin, as all Bard students do, with the Language and Thinking Program (L&T) before proceeding to First-Year Seminar (FYSEM) and the liberal arts curriculum familiar to all Bardians.

The PBS documentary College Behind Bars will make all this, and much more, familiar to the wider world. We encounter students, professors, and staff describing the program and their individual experiences. By foregrounding the voices of students and alumni/ae, the film asks viewers to examine their own assumptions—about college, about prison, about who belongs in those spaces and about what they are for. We see where students live and go to school, their discussions with each other and their professors, and we hear their family members reflect. We are moved to think differently and more deeply about what is going on behind the walls of our carceral institutions as well as our educational ones.

Director Lynn Novick and cinematographer Buddy Squires on location at Eastern New York Correctional Facility (Skiff Mountain Films)

One of the striking things about this film, and about BPI as well, is that it makes no attempt to soften or elide the violence that brought so many people to prison. There is no implication that the only incarcerated people deserving of visibility are those who are locked up for nonviolent offenses or “victimless” crimes. It confronts and disrupts the prevalent discourse on criminal justice reform, which focuses on the injustice of locking away for so long so many people whose crimes were less frightening. The film emphasizes the humanity, depth, and complexity of people who caused real harm and have confronted it—who, in their own telling, confront it every day. It makes the argument that they must not, as social justice activist Bryan Stevenson puts it, be defined by the worst thing they ever did. Their lives do not stop when we lock them away.

I began teaching for BPI in 2008, when the full-time administrative staff consisted of four or five people. Today BPI employs more than 30 full-time and another 20 part-time staff, a significant number of whom are Bard and BPI alumni/ae. Every year we offer 160 courses across those six sites. BPI has recently expanded to include two Bard Microcollege campuses outside of prison, in Holyoke, Massachusetts, and Brooklyn, New York. In partnership with community-based organizations, we offer the same associate’s degree to students whose pursuit of higher education has been thwarted by poverty and racism.

One of the things I found myself saying to those new students at Taconic was that Bard people everywhere recognize each other. In describing this phenomenon to me recently, Michael Crawford ’15 said, with a kind of wonder, that he’s realized that BPI is a “brand.” Crawford was incarcerated at 17 and released this past January on clemency after 20 years. When he meets someone who went to Bard, there are certain things he knows instantly about them because of his own experience. We connect, across generations and locations—we know one another. I used to think it was because Bard drew certain kinds of people, but now I understand that it’s because Bard shapes certain kinds of people. The College makes us Bardian. What BPI has taught me is that it’s not the place itself—special, beautiful, transformative though Annandale is. But if not the place, what is it that connects us?

Left: Bard Prison Initiative (BPI) students in a literature seminar at Taconic Correctional Facility. Right: Bard Prison Initiative (BPI) students conjugate Spanish verbs at Eastern New York Correctional Facility. (Skiff Mountain Films)

It’s the work. In Bard classrooms, art studios, and laboratories, students are taken seriously and are held to account, and they return the favor. BPI is prototypically Bard because of what happens in the classroom and the relationships that creates. BPI epitomizes the spirit of Bard not just because it was built by Bard undergraduates whose sense of possibility—and responsibility—was fed by their educational experience. It is also not simply because the College has required from the beginning that Bard courses and degrees in prison answer the same needs and meet the same standards as those in Annandale, though that is crucial to BPI’s identity and effectiveness. Likewise, the fact that BPI offers rigorous, expansive, intense liberal arts education in unlikely places is very Bard (especially in the 21st century), but none of this is what makes BPI so Bard.

Dorothy Crane worked in Annandale for years, as a counselor and in academic resources. She has been a part of BPI since early on, as an academic adviser and Senior Project writing consultant. She says that BPI is “Bard distilled. The essence. At the core there’s this belief that every student has something of value to give. They have something important to say, and Bard gives them the tools to say it so that people will understand and attend to their ideas. The core is in the relationships.” BPI students are seen and heard. There’s no small irony in this, of course, in a prison environment. We’re not surveilling them, but we are taking them seriously and treating actions and speech as if they really matter. Coursework happens at human scale, advising is one-on-one, classes are seminar sized, and —ultimately—the relationship with the institution is intimate and long-term.

BPI students enter the College through a subjective, idiosyncratic admission process that prioritizes the present and future over the past. We do not look at anyone’s educational history; we assume that many terrific candidates have had terrible relationships with institutions in the past—including schools. Applicants are not prescreened or admitted based on a consideration of their crime of conviction, length of sentence, or disciplinary record; they are representative of New York’s incarcerated population. We make no pretense that most are in prison for nonviolent offenses, wrongly convicted, or otherwise exceptional among incarcerated New Yorkers. This is central to our ethos as educators, and we are unapologetic and uncompromising about it. BPI students are likewise typical of the larger incarcerated population in that many are serving or have served very long sentences, and were often locked up very young. One of the things that is radical about BPI’s engagement with students is that we make a point of not knowing or involving ourselves with what brought them to prison or their disciplinary record. Our only interface regarding prison discipline has to do with whether it will cause them to miss class.

When I was in graduate school, one of my mentors insisted that the trope of dehumanization so frequently used to describe the totalizing institution of U.S. slavery was deeply mistaken. By definition, humans cannot be dehumanized. One might argue that to characterize a person as dehumanized is to participate in, or unconsciously assent to, their oppression, to naturalize the idea that people can be denatured. College-in-prison gives this idea the lie in a profound and immediate way. BPI students who were seen—and too often pushed to see themselves—as limited, incapable, “at risk,” a “problem,” lay claim to and express their intellectual, creative, and expansive humanity through the act of reading, rereading, analyzing, questioning, and rethinking Plato, Du Bois, Nietzsche, Morrison; learning calculus; or debating medical ethics. A young woman who “couldn’t do math” discovers that in fact she wants to be a math major. This is the power of a liberal arts education in prison. The liberal education is designed to identify, cultivate, and extend those things that express and create our humanity most directly. Bard’s commitment to this endeavor is what makes BPI Bard, and BPI in turn makes Bard more Bard.

Jessica Neptune ’02, BPI’s director of national engagement, helps colleges and universities outside New York build their own colleges-in-prison. She was part of BPI from the beginning, and returned after completing a PhD in U.S. history, several years as an American Council of Learned Societies Public Fellow, and service on the Obama administration’s Federal Interagency Reentry Council. As an undergraduate, she came to BPI for personal reasons—a number of family members had been in prison—but also political ones. “I was one of many Bard students in those years who began to see the issue we now call mass incarceration as the central civil rights issue of our generation,” says Neptune. More than that, she adds, her Bard experience drove her desire to extend the reach of the College: “Bard opened the world up to me and allowed me to know myself in new ways—to imagine my place in the world differently. I was drawn to BPI because as a student I thought a lot about how so many people I knew back home would thrive at a college like Bard if they’d ever had the chance. They’d thrive and they would in turn make it a better place.”

Bard students in prison, like those in Annandale and across the College’s international network, must start where they are. But because the College takes them seriously, BPI students, too, are enabled and encouraged to critically engage—not just imbibe—the insights, discoveries, and arguments of others. This means putting Shakespeare into conversation with James Baldwin in FYSEM, taking a seminar on the impact of migration on U.S. history and contemporary politics, tangling with ordinary differential equations, researching and writing a Senior Project on the eugenicist dangers of gene-editing technology or on the role of history and memory in formulating Korean-American identity. It’s a summer course exploring why Plato prioritized mathematics in his curriculum for a just society, and another that examines the notion of conflict and crisis in contemporary African states. It’s second-year, writing intensive courses on 20th-century French literature in translation, U.S. gentrification, or the politics and economy of modern Latin America.

BPI is a stripped-down version of Bard. Resources are scarce. We use chalkboards and pen and paper. Our computers are old, with no internet. We might be richer for it. Faculty are pushed to the edges of their knowledge by students’ questions, their voraciousness, the originality and power of their insights. As an administrator, one of my areas of responsibility is BPI’s writing curriculum. While it is the Bard curriculum, and our pedagogy is Bard’s—writing based and rigorous—I have made it my business to be in dialogue with students about their experience. I need to hear from them in order to continue developing and honing the courses. Students know they are responsible for their own education; part of living up to that responsibility is asking their questions and expressing their needs.

This can be a profoundly ambivalent thing. The College teaches us—or cultivates in us—criticality, a skepticism that makes no exceptions. Bard encourages us to question, and teaches us how to do it effectively, powerfully. Inevitably we come to question the College itself. It belongs to us and we belong to it, so naturally we cast our questioning eye upon it. We take it seriously as an object of critical examination and analysis. This, for the College, is a mark of success, but it is double-edged. We may not always acknowledge the power the College cultivated in us, the ways in which we are enriched and empowered by the skills of perspective, of questioning, of expression, and the awareness of possibility the College teaches us. For students inside, such criticality can be very familiar—the carceral space readily feeds skepticism. As hard as it is, we welcome critical questioning from students. We want them to advocate for themselves, to be demanding, to make as much use of the College as they can. We want them to ask questions and to expect to be heard and challenged.

One of my first students at BPI, Sylvester Reddick ’10, is now associate director of BPI-TASC, a high school equivalency course taught by BPI alumni/ae in partnership with a community-based organization in Brownsville, Brooklyn. Reddick speaks eloquently of his realization that college was, in fact, for him; that the classroom was his space; that the work was his work. He talks about how he tries to instill that feeling in his own students, that sense of ownership and belonging that he gained as a Bard student who had always liked school but had not always felt it was a place where his needs and interests were recognized or seen as legitimate.

Students at Bard must examine and rethink prior assumptions and metabolize previously unimagined perspectives and information. And they must do it in concert and contention with each other. This is another of the points we emphasize at orientation: they must be able to disagree. They must learn to read together, to think together, to use their conflicting ideas to sharpen themselves, not destroy one another. This is difficult anywhere, and it may be particularly challenging in prison. But they do it, and they do it well. The BPI Debate Union’s famous victory over Harvard in 2015, and our subsequent defeats of Cambridge, Morehouse, West Point, and others, all attest to students’ work ethic—they work harder and with fewer resources than anyone. These victories also show that disagreement is another area of possibility and growth, and that they embrace the challenges that confront them.

Bard Prison Initiative (BPI) Debate Union defeats Harvard University in September, 2015. (Skiff Mountain Films)

Danielle Riou, associate director of Bard’s Human Rights Project (HRP), was involved in the earliest days of BPI. She feels that one of BPI’s effects on Bard has been to make the College more nimble, more adaptable, more daring. “In some way, BPI helped to change the culture at Bard,” says Riou. “It made us more amenable to trying new models of education, but not only that, to thinking about higher ed as something that isn’t confined to a traditional campus.” She says that BPI has helped Bard better “imagine itself,” and to live up to its vision. Annandale students who tutor for BPI frequently find that their relationship to their own education is changed by their experience with BPI students and the urgency with which they approach their coursework. The stakes are very high, and this intensity often pushes their fellow undergraduates to think differently about their own work. As a tutor at Coxsackie Correctional Facility, Tayler Butler ’17 was profoundly affected by the seriousness and diligence of the BPI students she worked with. “Through my work at BPI, I learned to value my education, to truly appreciate the freedom that it brought me,” says Butler, who is now director of student services and enrichment at Bard Early College New Orleans. “As an educator, I am passionate about teaching my students to do the same.”

Having been both inspired and challenged by the seriousness with which Bard took me and my intellect at a young age, I have felt pushed to live up to the image of myself I developed as a Bard student. As an undergraduate I connected powerfully with the people I found at Bard. At those orientations, when we welcome new students to BPI and the College, we describe the intensity of the academic work incoming students can expect and the layers of connectedness that bind students to the institution and to one another through years of study and long after. Introducing himself to new students, Kenner tells them that one of the things that inspired the idea of BPI at the outset was a sense of indebtedness to the College, and the need for the College to be in new and different spaces.

BPI has set a new standard for college-in-prison nationwide. More than 1,000 students have enrolled; some 600 alumni/ae have now returned home, committed to engaging their communities. They deploy their education in myriad ways, but always they do it in concert with one another across personal, professional, and civic life. My Bard friends are still among the people most important to me. As a professor at BPI, I connect again as a Bardian, with students who are Bardians, through the work we do together and through the expectations we have of each other—to push our thinking, to rise to the challenges of the text, of the question, of the possibility.

Delia Mellis ’86 is director of program and faculty development for BPI and an associate in Bard’s Institute for Writing and Thinking. She holds a PhD in U.S. history. Like most BPI administrators (and many in Annandale), she continues to teach.

(Photo by Karen Pearson)